The diagnostic work-up

Even when a patient is sent to the ED, the FP plays a critical role in his or her continuing care. FPs will often coordinate with inpatient care and manage transition of care to the outpatient setting. (And in many communities, the ED or hospital physicians may themselves be family practitioners.)

In terms of care, not even an aspirin should be administered in a case like this because the patient has not yet had any neuroimaging, and differentiation of ischemic from hemorrhagic stroke cannot be made on clinical grounds alone. Once an ischemic stroke is confirmed, determining the etiology is critical given the significant management differences between the different types of stroke (atherosclerotic, cardioembolic, lacunar, or other).

Which imaging method, and when?

While a computerized tomography (CT) scan is the preferred initial imaging strategy for acute stroke to discern the ischemic type from the hemorrhagic, MRI is preferred for the evaluation of acute ischemic stroke because the method has a higher sensitivity for infarction and a greater ability to identify findings (such as demyelination) that would suggest an alternative diagnosis.

In addition to evaluating the brain parenchyma, physicians must also assess the cerebral vasculature. CT angiography (CTA) or MR angiography (MRA) of the head and neck are preferred over carotid ultrasound because they are capable of evaluating the entire cerebrovascular system12,13 and can be instrumental in identifying potential causes of stroke, as well as guiding therapeutic decisions. Carotid ultrasound is a reasonable alternative for patients presenting with symptoms indicative of anterior circulation involvement when CTA and MRA are unavailable or contraindicated, but it will not identify intracranial vascular disease, proximal common carotid disease, or vertebrobasilar disease.

Getting to the cause of suspected stroke: Labs and other diagnostic tests

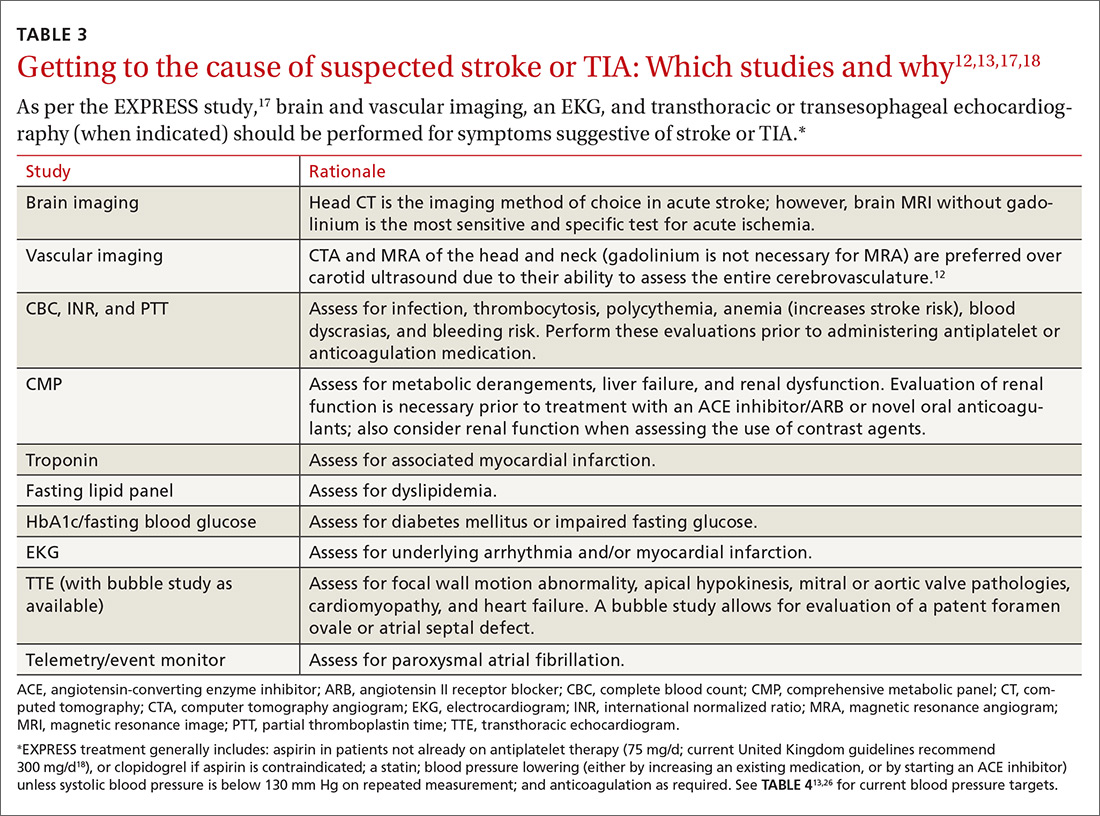

A routine work-up includes BP checks, routine labs (complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, coagulation profile, and troponin), an electrocardiogram (EKG), a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) with bubble study if possible, and a minimum of 24 to 48 hours of cardiac rhythm monitoring. Cardiac rhythm monitoring should be extended in the setting of clinical concern for unidentified paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, such as an embolism without a proximal vascular source, multiple embolic infarcts in different vascular territories, a dilated left atrium, or other risk factors for atrial fibrillation that include smoking, systolic hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure (see TABLE 312,13,17,18).14-16 This standard diagnostic work-up will identify the cause of stroke in 70% to 80% of patients.19

Additional investigations to consider if the etiology is not yet elucidated include a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), cerebral angiography, a coagulopathy evaluation, a lumbar puncture, and a vasculitis work-up. If available, consultation with a neurologist is appropriate for any patient who has had a stroke or TIA. Patients with unclear etiologies or for whom there are questions concerning strategies for preventing secondary stroke should be referred to Neurology and preferably a stroke specialist.

Timing matters, even when symptoms have resolved (ie, TIA).11,20 The EXPRESS trial17 (the Early use of eXisting PREventive Strategies for Stroke) looked at the effect of urgent assessment and treatment (≤1 day) of patients presenting with a TIA or minor stroke on the risk of recurrent stroke within 90 days. The diagnostic work-up included brain and vascular imaging together with an EKG. This intensive approach led to an absolute risk reduction of 8.2% (from 10.3% to 2.1%) in the risk of recurrent stroke at 90 days (number needed to treat [NNT]=12).17

Expedited work-up and treatment was also recently evaluated in a non-trial, real-world setting and was associated with reducing recurrent stroke by more than half the rate reported in older studies.20 Overall, the data suggest that evaluation within 24 hours confers substantial benefit, and that this evaluation can happen in an outpatient setting.21-23