In April of this year, 3 counties in Minnesota reported a measles outbreak, illustrating the danger of vaccine hesitancy that exists in some communities, resulting in low rates of childhood immunization. Fifty people—mostly children under the age of 5 and almost all unimmunized—have been diagnosed with measles since this outbreak began. As of early May, 11 had been hospitalized. Most of those infected have been American-born children of Somali immigrants.1,2

At the time of the outbreak, only 42% of the Somali children had been immunized against measles, compared with 88.5% of non-Somalis in Minnesota.2 Because of concern about the number of Somali children being diagnosed with autism, a condition apparently not recognized in Somalia, Somali parents living in Minnesota began questioning why this was occurring.

High profile anti-vaccine advocates reportedly visited the community and advised these parents that the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine was the cause of this rise in autism incidence and encouraged them to avoid the vaccine.2 This series of events led to low vaccination rates in what was once a well-vaccinated community. The outbreak appears to have started with a Somali child who visited Africa and then returned to his community while incubating measles.

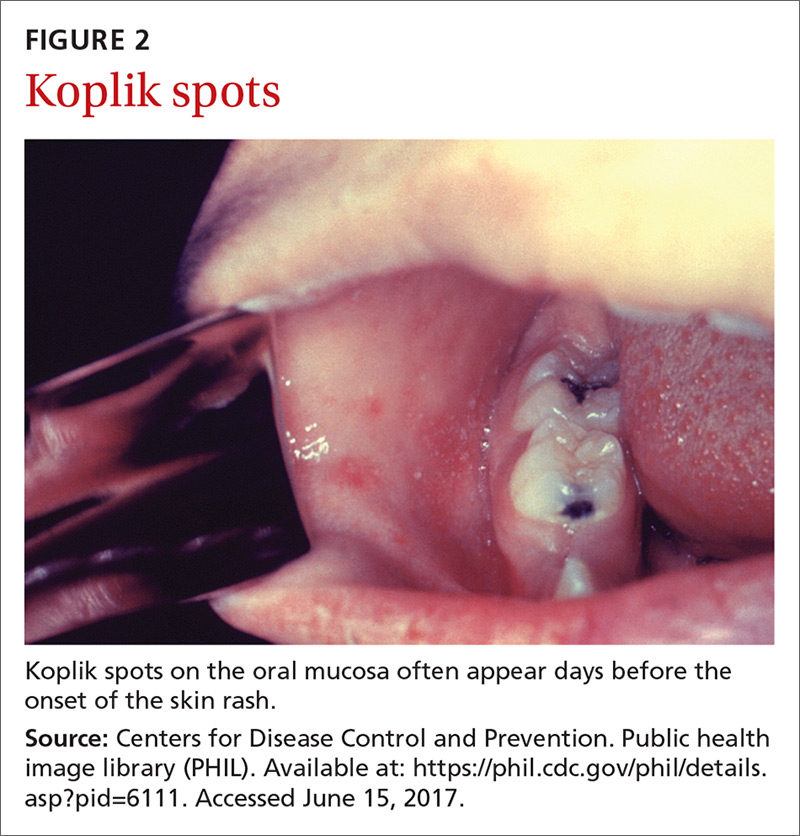

The clinical course of measles. Measles is an acute viral respiratory illness, which, after an incubation period of 10 to 12 days, starts with a fever (as high as 105° F), malaise, and at least one of the 3 “C”s—cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis.3,4 A maculopapular rash then starts on the face and spreads to the trunk and the extremities (FIGURE 1). Koplik spots (FIGURE 2) can be seen on the oral mucosa. Children with measles look very ill. Patients are contagious for approximately 8 days, starting 4 days before the rash appears. Complications can include otitis media, bronchopneumonia, encephalitis, and diarrhea.

Measles is not a benign childhood illness. Before the licensure of live measles vaccine in 1963, an average of 549,000 measles cases were reported in the United States each year.3 That number is likely an underestimate due to inconsistent reporting, with a more plausible number of infections annually being 3 to 4 million.3 These regular epidemics led each year to about 48,000 people being hospitalized from complications, 1000 developing chronic disability from acute measles encephalitis, and about 500 dying from measles-related complications. Today, worldwide, an estimated 134,200 individuals die from measles each year.3

Where the risk is greatest. In the year 2000, measles was declared eliminated from the United States, meaning that endemic transmission was no longer occurring. Since then, the annual number of cases has ranged from a low of 37 in 2004 to a high of 667 in 2014.3 Most measles cases have occurred in unvaccinated individuals and primarily through importation by people infected in other countries who then transmit the infection upon entry or reentry to this country. In the United States, measles is more likely to spread and cause outbreaks in communities where large groups of people are unvaccinated.

Laboratory confirmation of measles is important to establish a correct clinical diagnosis, as well as to verify the infection for public health purposes. Confirmation is achieved by detecting in a patient’s blood sample the measles-specific IgM antibody or measles RNA by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Obtain both a serum sample and a throat swab (or nasopharyngeal swab) from patients you suspect may have measles. Urine samples may also contain virus, and can be useful. The local health department can offer advice on how to collect and process these laboratory specimens.

Measles is a preventable infection

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends routine childhood immunization with MMR vaccine, with the first dose given at age 12 through 15 months, and the second dose at 4 through 6 years of age (or at least 28 days following the first dose).3,5 Others for whom the vaccine is recommended are included in the TABLE.3