MADRID – Ninety-five percent of cases of enterovirus and parechovirus meningitis in infants younger than 90 days old in the United Kingdom and Ireland were diagnosed through lumbar puncture and identification of the virus in the CSF by PCR, Seilesh Kadambari, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“We recommend that routine testing of CSF for enterovirus and parechovirus in febrile infants should be promoted, even in the absence of pleocytosis,” said Dr. Kadambari of John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, England.

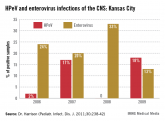

He presented highlights of a comprehensive prospective observational surveillance study conducted across the United Kingdom and Ireland to assess the burden of enterovirus and parechovirus meningitis in infants younger than 90 days old.This active enhanced prospective surveillance study was undertaken because an earlier retrospective study concluded that the rate of viral meningitis across all pediatric and adult age groups had increased rapidly during a recent 10-year period in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Infants younger than 3 months of age were especially hard hit by enterovirus, which accounted in the earlier study for 92% of all viral meningitis cases in that age group. Dr. Kadambari and his coinvestigators decided to take a closer prospective look at the sub-3-month age group because it’s such an important time neurodevelopmentally.

During the 13-month period of June 2014 to June 2015, 710 patients younger than 90 days old were hospitalized for enterovirus or parechovirus meningitis across the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland. Ninety-five percent were due to enterovirus. Only 6% of affected infants were born prematurely.

“One of the take-home messages for me from the study was that 12% of enterovirus cases and 23% of parechovirus meningitis cases required admission to an ICU setting,” the pediatrician observed.

Among the infants admitted to a pediatric ICU, half of those with enterovirus meningitis and all those with parechovirus meningitis required intubation and mechanical ventilation. One-fifth of the enterovirus meningitis patients in pediatric ICUs required inotropic support for cardiovascular stabilization, as did all young infants with parechovirus meningitis.

Among the 710 patients, the three most common clinical presenting features were fever, irritability, and reduced feeding, present in 85%, 66%, and 54%, respectively.

Upon physical examination, two noteworthy common findings were signs of shock, present in 27% of infants with enterovirus meningitis and 43% with parechovirus meningitis, and respiratory distress, seen in 12% and 26%, respectively.

None of the 710 infants had a secondary bacterial infection. “That has implications for antimicrobial stewardship programs,” according to Dr. Kadambari.

The majority of infants had a normal CSF WBC count and a normal-range C-reactive protein level.

“Raised inflammatory markers were not a common feature in our cohort,” he noted.

Two infants died: one of a massive pulmonary hemorrhage and the other as a result of septic shock. Of the remaining 708 patients, however, 699 (98.7%) were discharged without significant neurologic impairment. Seven infants with enterovirus meningitis and two with parechovirus meningitis were discharged with severe delay, including cases of fine motor and gross motor delay, visual abnormalities, and a single case of severe cardiac dysfunction requiring discharge on an ACE inhibitor.

This surveillance study was a collaboration between St. George’s University of London and Public Health England. Dr. Kadambari reported having no financial conflicts.

Future studies need to examine long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes in affected young infants out to age 24 months, he said.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com