A 70-year-old man is evaluated for a persistent leukocytosis. He was hospitalized 10 days ago for a severe exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He was intubated for 3 days, was diagnosed with a left lower lobe pneumonia, and was treated with antibiotics. His white blood cell count on admission was 20,000 per mcL. It dropped as low as 15,000 on day 6 but is now 25,000, with 23,000 polymorphonuclear leukocytes (10% band forms). He is on oral prednisone 15 mg once daily. Chest x-ray shows no infiltrate. Urinalysis without WBCs.

What is the most likely cause of his leukocytosis?

A) Pulmonary embolus.

B) Lung abscess.

C) Perinephric abscess.

D) Prednisone.

E) Clostridium difficile infection.

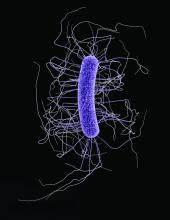

This isn’t an uncommon scenario, in which your hospitalized patient has a climbing WBC without a clear cause. Often, the patient may well be improving from the condition that they were originally hospitalized for, but the climbing WBC count is concerning and often delays discharge. What should we think of in the patient whose WBC climbs in the hospital, and the cause isn’t readily apparent?The most likely diagnosis in otherwise unexplained leukocytosis in a hospitalized patient is C. difficile.

Anna Wanahita, MD, of the St. John Clinic in Tulsa, Okla., and her colleagues prospectively studied 60 patients admitted to a VA hospital who had unexplained leukocytosis.1 All patients had stool specimens sent for C. difficile toxin; in addition, 26 hospitalized control patients without leukocytosis also had stool sent for C. difficile toxin. For study purposes, leukocytosis was defined as a WBC greater than 15,000 per mcL. Any patient for whom C. difficile toxin was sent because of clinical suspicion and who was positive was excluded from the study results.

Almost 60% of the patients with unexplained leukocytosis (35 of 60) had a positive C. difficile toxin, compared with 12% of the controls (P less than .001). More than half of the patients with a positive C. difficile test had the onset of leukocytosis prior to any symptoms of colitis. Leukocytosis responded to treatment with metronidazole in 83% of the patients with a positive C. difficile toxin, and 75% of the patients who had leukocytosis did not have a positive C. difficile toxin.

In another study, Mamatha Bulusu, and colleagues did a retrospective study of 70 hospitalized patients who had diarrhea and underwent testing for C. difficile.2 They evaluated the pattern of white blood cell counts in patients who were positive and negative for C. difficile toxin. The mean WBC for C. difficile–positive patients was 15,800, compared with 7,700 for the patients who were C. difficile negative (P less than .01). They described three patterns: one in which leukocytosis occurred at the onset of diarrhea; a pattern in which unexplained leukocytosis occurred days prior to diarrhea; and a pattern in which patients treated for infection with leukocytosis had a worsening of their leukocytosis at the onset of diarrheal symptoms. Treatment with metronidazole led to a resolution of leukocytosis in all the C. difficile–positive patients.

Another possibility in this case was WBC elevation because of the patient’s prednisone. Prednisone can increase WBC as early as the first day of therapy.3 The elevation and rapidity of increase are dose related. The important pearl is that steroid-induced leukocytosis involves an increase of polymorphonuclear white blood cells with a rise in monocytes and a decrease in eosinophils and lymphocytes.

Importantly, increased band forms (greater than 6%) and toxic granulation rarely ever occur with steroid-induced leukocytosis, and the presence of these features should strongly suggest a different cause.4Pearl: Think of underlying C. difficile infection in your hospitalized patient with unexplained leukocytosis.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

References

1. Am J Med. 2003 Nov;115(7):543-6.

2. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Nov;95(11):3137-41.