Fifteen years ago, reported cases of syphilis in the United States were so infrequent that public health officials thought it might join the ranks of malaria, polio, and smallpox as an eradicated disease. That turned out to be wishful thinking.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 2012 and 2015, the overall rates of syphilis in the United States increased by 48%, while the rates of primary and secondary infection among women spiked by 56%. That was a compelling enough rise, but fresh data from the agency indicate that the overall rates of syphilis increased by 17.6% between 2015 and 2016, and by 74% between 2012 and 2016.

These trends prompted the CDC to launch a “call to action” educational campaign in an effort to curb the rising syphilis rates. The United States Preventive Services Task Force also is taking action. It recently posted a research plan on screening pregnant women for syphilis that will form the basis of a forthcoming evidence review and, potentially, new recommendations.

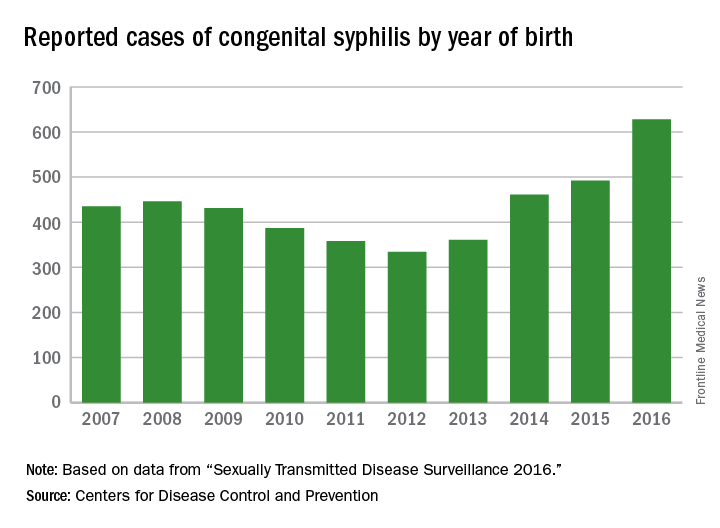

“We are really concerned about this trend,” Sarah Kidd, MD, MPH, medical officer in the division of STD Prevention at the CDC, said in an interview. “It’s troubling that we’re seeing this resurgence, especially among women and infants, since the consequences are so dire.”observed in all regions of the United States during the same time period, said Dr. Kidd, who coauthored a 2015 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on the topic (MMWR. 2015 Nov 13;64[44]:1241-5). That analysis found that during 2012-2014, the number of reported CS cases in the United States increased from 334 to 458, which represents a rate increase from 8.4 to 11.6 cases per 100,000 live births. This contrasted with earlier data, which found that the overall rate of reported CS had decreased from 10.5 to 8.4 cases per 100,000 live births during 2008-2012.

In 2016, there were 628 reported cases of CS, including 41 syphilitic stillbirths, according to the CDC.

“Congenital syphilis rates tend to track female syphilis rates; so as female rates go up, we know we’re going to see a rise in congenital syphilis rates,” Dr. Kidd said. “One way to prevent syphilis is to prevent female syphilis altogether. Another way is to prevent the transmission from mother to infant when you have a pregnant woman with syphilis.”

Lack of prenatal care

CDC guidelines recommend that all pregnant women undergo routine serologic screening for syphilis during their first prenatal visit. Additional testing at 28 weeks’ gestation and again at delivery is warranted for women who are at increased risk or live in communities with increased prevalence of syphilis infection. That approach may seem sensible, but such prevention measures are ineffective when mothers don’t receive any prenatal care or receive it late, which happens in about half of all CS cases, Dr. Kidd said.

Inconsistent, inadequate, or a total absence of prenatal care is “probably the biggest risk factor for vertical transmission, especially among high-risk populations, where there is an increased background prevalence of syphilis in childbearing women,” said Robert Maupin, MD, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology in the section of maternal-fetal medicine at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans.

“That’s not dissimilar to our prior experience with perinatally acquired HIV,” he said. “Once we developed the tools in terms of effective antiretroviral therapy, which was able to disrupt perinatal transmission, we saw that the children who became infected were in fact those whose mothers did not adequately participate in prenatal care. Sometimes it’s a total lack of care; sometimes it’s presenting very late in pregnancy.”To complicate matters, women who receive no or inconsistent prenatal care face an increased risk for preterm birth, Dr. Maupin noted. So while a clinician might follow CDC recommendations that pregnant women with confirmed or suspected syphilis complete a course of long-acting penicillin G for at least 30 days or longer before the child is born, “the timing of being able to implement effective prevention and treatment prior to that 30-day window can sometimes be compromised by the fact that she ends up delivering prematurely,” he said. “If someone’s not adequately linked to consistent prenatal care, she may not complete that full course of prevention. Additionally, patterns of care are often fragmented, meaning that patients may go to one clinic or one provider, may not return, and may end up switching to a different clinic. That translates into a potential lag in implementing treatment or making a diagnosis in the first place, and that may be disruptive in the context of our attempted prevention measures.”

Precise reasons why some pregnant women in the United States receive no or inadequate prenatal care remain unclear.

“Anecdotally, in the West, I hear that women with drug abuse histories or drug abuse issues [are vulnerable], or they may be homeless or have mental health issues,” Dr. Kidd said. “In other areas of the country, people feel that it’s more of an insurance or access to care issue, but we don’t have data on that here at the CDC.”