Over the past 3 decades, age-adjusted mortality for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the United States has dropped by more than 50%.1 While multiple factors have contributed to this remarkable decline, the introduction and widespread use of statin therapy is unquestionably one key factor. Despite nearly overwhelming evidence that statins effectively lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and predictably reduce cardiovascular events, less than half of patients with clinical coronary heart disease receive high-intensity statin therapy, leaving this population at increased risk for future events.2

Statins: Latest evidence on risks and benefits

Statins aren’t perfect. Not every patient is able to achieve the desired LDL-C lowering with statin therapy, and some patients develop adverse effects such as myopathy, new-onset diabetes, and occasionally hemorrhagic stroke. A recent report puts the risks of statin therapy in perspective, estimating that the treatment of 10,000 patients for 5 years would cause one case of rhabdomyolysis, 5 cases of myopathy, 75 new cases of diabetes, and 7 hemorrhagic strokes.3 The same treatment would avert approximately 1000 CVD events among those with preexisting disease, and approximately 500 CVD events among those with elevated risk, but no preexisting disease.3

In blinded randomized controlled trials, statin therapy is associated with relatively few adverse events (AEs). In open-label observational studies, however, substantially more AEs are reported. During the blinded phase of one recent study, muscle-related AEs and erectile dysfunction were reported at a similar rate by participants randomly assigned to receive atorvastatin or placebo. During the nonblinded nonrandomized phase, complaints of muscle-related AEs were 41% more likely in participants taking statins compared with those who were not.4

Statin therapy offers predictable CVD risk reduction. The evidence report accompanying the 2016 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines on statins for the prevention of CVD states that the use of low- or moderate-dose statin therapy was associated with an approximately 30% relative risk reduction (RRR) in CVD events and in CVD deaths, and a 10% to 15% RRR in all-cause mortality.5 Those with greater baseline CVD risk will have greater absolute risk reduction (ARR) than those with low baseline risk.5

How effective are non-statin therapies?

Multiple studies have demonstrated that some drugs can favorably modify lipid levels but not improve patient outcomes—eg, niacin, fibrates, and omega-3 fatty acids. The therapies that do improve outcomes are those that act via upregulation of LDL-receptor expression: statins, ezetimibe, bile acid sequestrants, dietary interventions, and ileal bypass surgery.

A recent meta-analysis found that with a 38.7-mg/dL (1-mmol/L) reduction in LDL-C level, the relative risk for major vascular events was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.71-0.84) for statins and 0.75 (95% CI, 0.66-0.86) for monotherapy with non-statin interventions that upregulate LDL-receptor expression.6

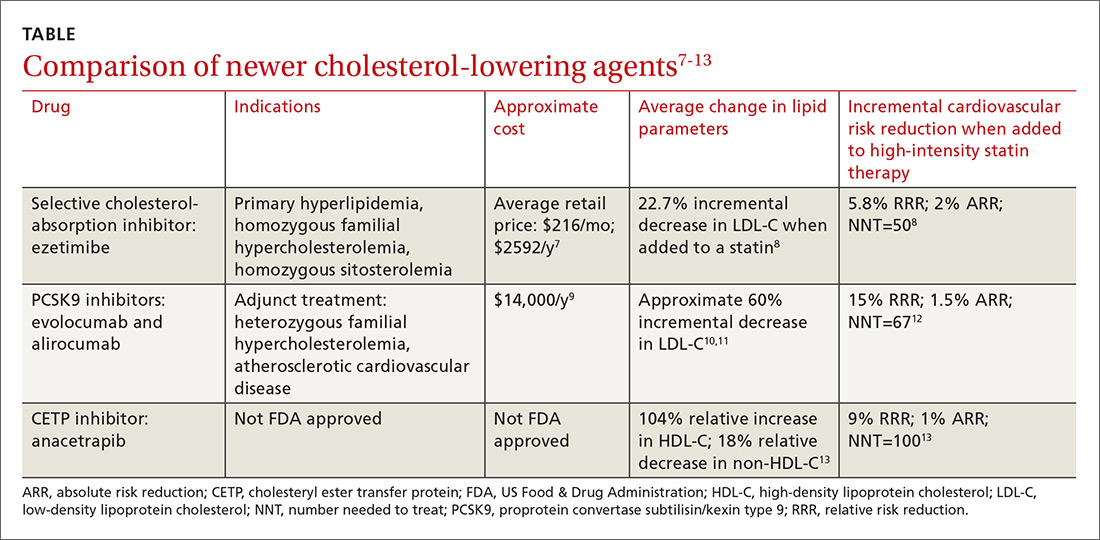

Ezetimibe. Less impressive is the incremental benefit of adding some non-statin therapies to effective statin therapy. The IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT) reported that adding ezetimibe to effective statin therapy in stable patients with previous acute coronary syndrome reduced the LDL-C level from 69.5 mg/dL to 53.7 mg/dL (TABLE7-13).8 After 7 years of treatment, relative risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) outcomes decreased by 5.8%; absolute decrease in risk was 2%: from 34.7% to 32.7% (number needed to treat [NNT]=50).8 Consider adding ezetimibe to maximally-tolerated statin therapy for patients not meeting LDL-C goals with a statin alone.

Continue to: A new class to lower LDL-C: PCSK9 inhibitors