As members of the baby boomer generation (adults ≥65 years) age, the number of people at risk for diabetes increases. Already nearly one-quarter of people over age 65 have type 2 diabetes (T2DM).1 With a proliferation of new medications to treat diabetes, deciding which ones to use in older patients is becoming complex.

In this article we review the important issues to consider when prescribing and monitoring diabetes medications in older adults. To provide optimal patient-centered care, it’s necessary to assess comorbid conditions as well as the costs, risks, and benefits of each medication. Determining appropriate goals of therapy and selecting agents that minimize the risk of hypoglycemia will help ensure safe and effective management of older patients with diabetes.

What makes elderly patients unique

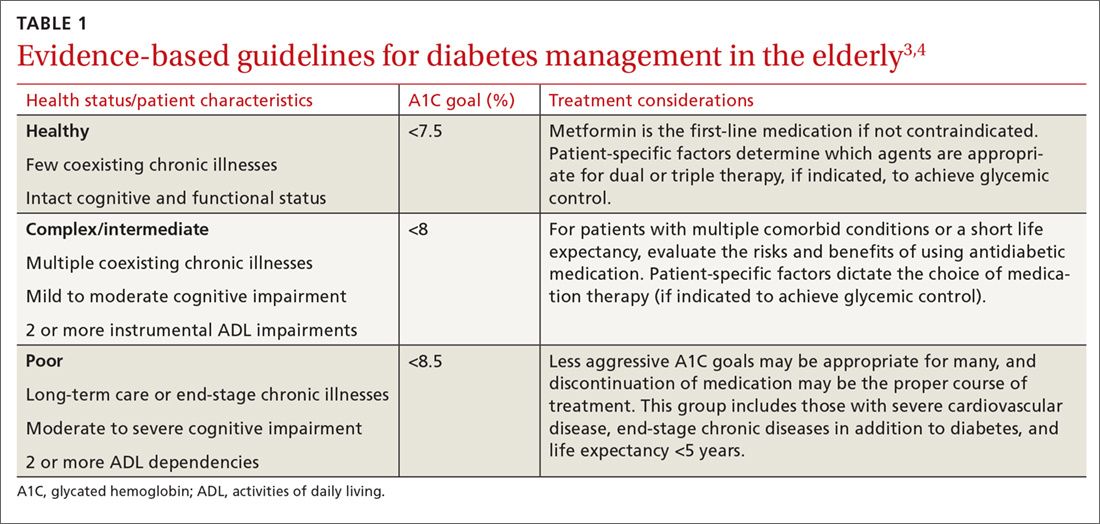

The pathophysiology of T2DM in the elderly is unique in that it involves not just insulin resistance but also age-related loss of beta-cell function, leading to reduced insulin secretion and altered effectiveness of pharmacotherapy.2 The addition of second and third medications may be needed for those with longstanding T2DM, although these agents often reduce the A1C level to a lesser extent than when used as monotherapy in patients whose beta-cell function is still intact. In addition to physiologic changes, older adults with diabetes have varied general health statuses and care support systems. The goal for glycemic management should be personalized based on an individual’s comorbidities and physical and cognitive functional status (TABLE 13,4).2

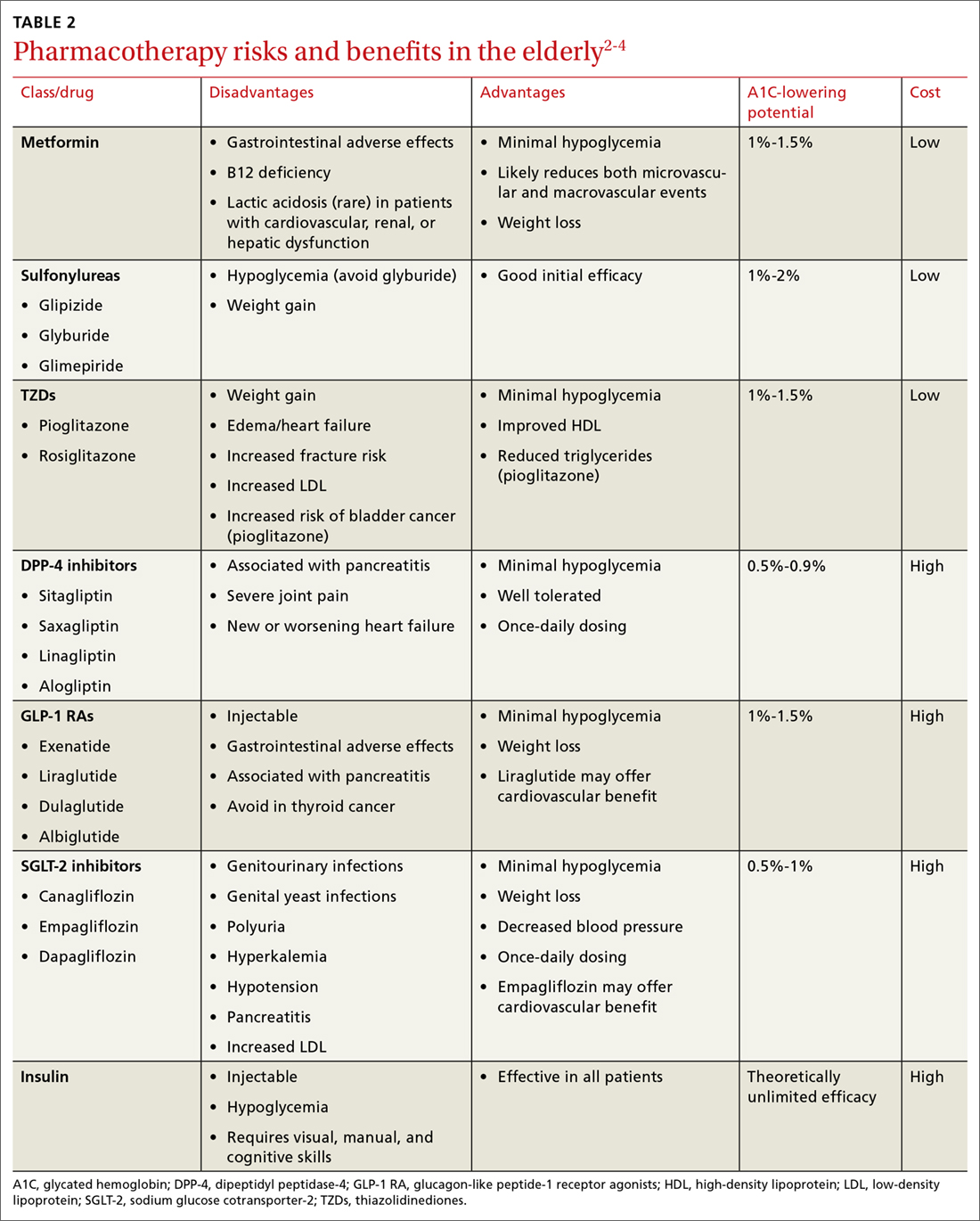

Higher A1C goals can be acceptable for elderly patients with comorbid conditions such as cognitive dysfunction, dementia, or cardiovascular or renal disease. Evaluate cognition when determining appropriate pharmacotherapy. Assess a patient’s awareness of hypoglycemia and ability to adhere to the regimen prescribed. Visual impairment, decreased dexterity, baseline weight, nutritional and functional status, as well as social support, finances, and formulary restrictions should all be considered when determining the most appropriate regimen for a patient. Also take into account patient and family goals of care.2 TABLE 22-4 summarizes key risks and benefits of the medications we discuss next.

Metformin

Metformin is recommended as first-line therapy for those with T2DM for a number of reasons, including its potential to reduce cardiovascular events and mortality.3,5 It also significantly reduces A1C levels by 1% to 1.5%,6 while imparting a low risk of hypoglycemia. Metformin is cost effective and well tolerated, making it an excellent choice for use in older patients.

The most common adverse effects are abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, and weight loss. The use of extended-release preparations, as well as slow titration of dosing, can improve gastrointestinal (GI) tolerance. Weight loss may be an attractive side effect in patients who are overweight or obese, but weight loss and diarrhea are concerning effects in frail older adults who may have poor nutritional reserves.6

Monitor renal function frequently in older patients receiving metformin.3 Renal failure is a risk factor for adverse events such as lactic acidosis, and metformin is therefore contraindicated in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.4 With this in mind, metformin should not be started in patients with an eGFR below 45 mL/min/1.73 m2. And for patients already taking metformin, reduce the total daily dose if the eGFR falls to between 30 and 45 mL/min/1.73 m2.4

Metformin can cause a reduction in vitamin B12 levels after long-term use in up to 30% of patients, likely due to decreased absorption from the ileum.7 Monitor vitamin B12 serum concentrations periodically with long-term therapy, particularly in patients with peripheral neuropathy or anemia, as these conditions may be exacerbated by vitamin B12 deficiency.3,4

Continue to: Sulfonylureas