Thrombocytopenia and neutropenia are commonly encountered laboratory abnormalities. The presence of either requires that you promptly evaluate for life-threatening causes and identify the appropriate etiology. This article identifies key questions to ask. It also includes algorithms and tables that will facilitate your evaluation of patients with isolated thrombocytopenia or isolated neutropenia and speed the way toward appropriate treatment.

Thrombocytopenia: A look at the numbers

Thrombocytopenia is defined as a platelet count <150,000/mcL.1 The blood abnormality is either suspected based on the patient’s signs or symptoms, such as ecchymoses, petechiae, purpura, epistaxis, gingival bleeding, or melena, or it is incidentally discovered during review of a complete blood count (CBC).

The development of clinical symptoms is closely related to the severity of the thrombocytopenia, with platelet counts <30,000/mcL more likely to result in clinical symptoms with minor trauma and counts <5,000/mcL potentially resulting in spontaneous bleeding. While most patients will have asymptomatic, incidentally-found thrombocytopenia, and likely a benign etiology, those with the signs/symptoms just described, evidence of infection, or thrombosis are more likely to have a serious etiology and require an expedited work-up. Although pregnancy may be associated with thrombocytopenia, this review confines itself to the causes of thrombocytopenia in non-pregnant adults.

Rule out pseudothrombocytopenia

When isolated thrombocytopenia is discovered incidentally in an asymptomatic person, the first step is to perform a repeat CBC with a peripheral smear to confirm the presence of thrombocytopenia, rule out laboratory error, and assess for platelet clumping. If thrombocytopenia is confirmed and platelet clumping is present, it may be due to the calcium chelator in the ethylenediaminetetraacetic anticoagulant contained within the laboratory transport tube; this cause of pseudothrombocytopenia occurs in up to 0.29% of the population.1 Obtaining a platelet count from a citrated or heparinized tube avoids this phenomenon.

Is the patient’s thrombocytopenia drug induced?

Once true thrombocytopenia is confirmed, the next step is to review the patient’s prescribed medications, as well as any illicit drugs used, for potential causes of drug-induced thrombocytopenia. DITP can be either immune-mediated or nonimmune-mediated.

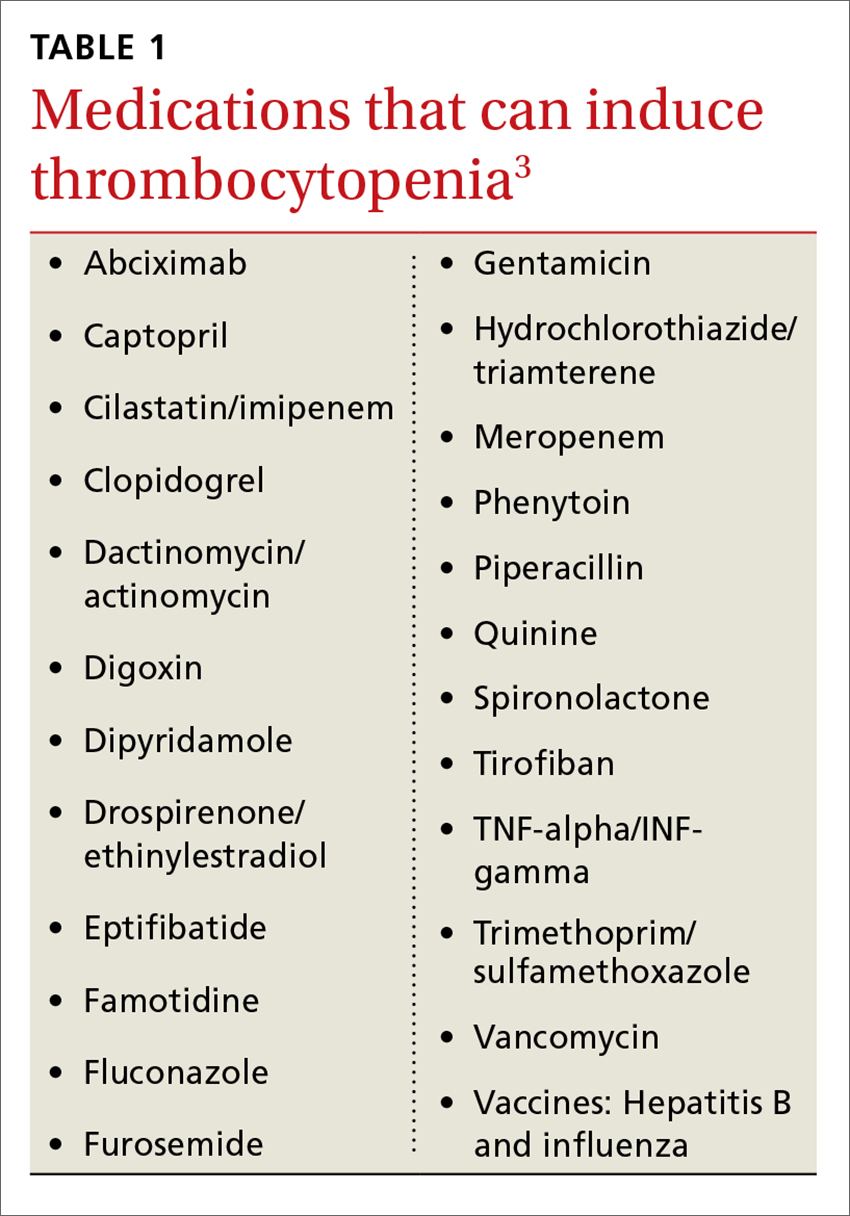

Immune-mediated DITP typically occurs within 1 to 2 weeks of medication exposure and begins to improve within 1 to 2 days of stopping the offending drug.2 (See TABLE 13 for a list of medications that can induce thrombocytopenia.) It should be noted that most patients who take the medications listed in TABLE 1 do not experience thrombocytopenia; nonetheless, it is a potential risk associated with their use.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a unique form of immune-mediated DITP in that it is caused by antibody complexes, resulting in platelet activation, clumping, and thrombotic events.4 HIT occurs <1% of patients in intensive care units, but can occur in any patient on long-term heparin therapy. It manifests as a >50% drop in platelet count within 5 to 14 days of the introduction of heparin; however, in those previously exposed to heparin, it can occur within 24 hours.4,5

Continue to: Non-immune-mediated DITP