according to data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

There were 74,229 such admissions in the United States that year – all others totaled 1.77 million – and the children at the highest risk for dermatology hospitalization were those living in communities with the lowest household incomes, the uninsured and those on Medicaid, and those living in the South, Justin D. Arnold of George Washington University, Washington, and his associates said in Pediatric Dermatology.

“Individuals from communities of low socioeconomic status may be more likely to be hospitalized because of gaps in insurance coverage, difficulty with transportation, or inconsistent access to preventative medical care, which for skin disease, would include access to an outpatient pediatric dermatologist,” they wrote.

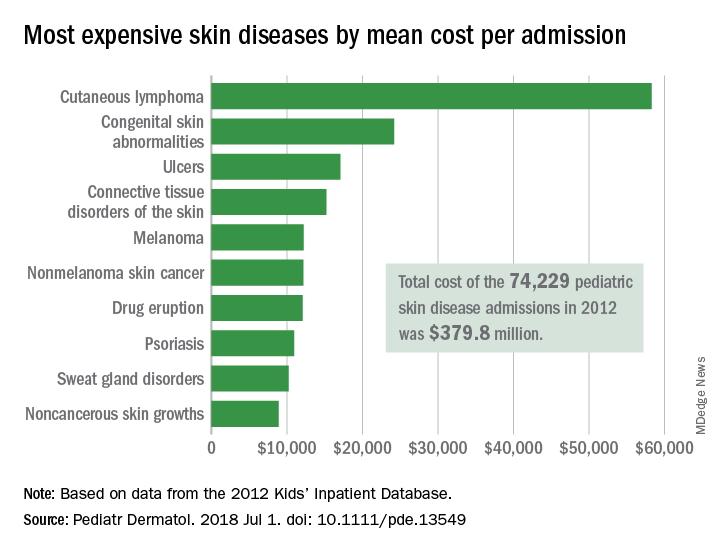

All those admissions for skin diseases cost the health care system $379.8 million in 2012, or 1.9% of the $20.3 billion spent on all pediatric hospitalizations, excluding those related to pregnancy or childbirth. The mean cost of a skin disease admission was $5,211 for a child aged less than 18 years, compared with $11,409 for nondermatology admissions, according to data from the 2012 Kids’ Inpatient Database, which includes records of pediatric discharges from 44 states.

Cutaneous lymphoma was the most expensive skin disease per admission at a mean cost of $58,294, with congenital skin abnormalities second at $24,186, and ulcers third at $17,064. Bacterial skin infections and infestations were only the 19th most expensive admission at $4,135, but it was by far the most common (59,115 admissions) and the most expensive overall, with a total cost of $240 million. The second most common condition was viral diseases with 3,812 admissions and the next most expensive total was $33.5 million for connective tissue disorders, Mr. Arnold and his associates said.

Multivariate models that adjusted for such factors as age, sex, and race revealed that “the risk of hospitalization for skin disease increased as the median income of one’s zip code declined,” the investigators noted. The adjusted odds ratio for hospitalization in the lowest-income quartile (less than $39,000) was 1.22, compared with the highest-income quartile.

Insurance status also affected hospitalization, putting children from families with no insurance (aOR, 1.35) and those on Medicaid (aOR, 1.17) at a disadvantage, compared with those who had private insurance. “Policy makers should consider increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates to outpatient dermatologists, which might encourage more clinicians to accept this form of insurance and thereby expand access to preventative skin care,” they said.

Regional differences also were observed, which put children from the southern states at the highest risk (aOR, 1.32), compared with those in the West, which could be related to access issues. “In 2016, 4 of the 10 communities in the United States with the lowest density of dermatologists were in the South, suggesting that the high rate of hospitalizations there may also be partially attributed to lack of access to dermatologists,” Mr. Arnold and his associates wrote.

The investigators did not report funding or disclose conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Arnold JD et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul 1. doi: 10.1111/pde.13549.