Lab tests. There are no specific laboratory markers for TAO. The initial evaluation should include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), complete metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA). Tests to exclude other autoimmune diseases include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticentromere antibody and Scl-70 to exclude CREST syndrome and scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibodies to exclude disorders of hypercoagulability, and drug testing and history-taking to evaluate for drug-related (eg, cocaine) etiologies. Further studies should be performed based on clinical suspicion.

Imaging. Patients with suspected TAO should undergo an arteriogram of the affected extremities and large arteries. Other imaging modalities include computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography. Biopsy is rarely indicated, unless there are atypical findings, such as large artery involvement or arterial nodules. Interestingly, a positive Allen test in a young smoker can be highly suggestive of TAO.1 (For a demonstration of the Allen test, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1tJO0RW9UM.)

Our patient tested negative for rheumatoid arthritis, CREST, and scleroderma and had a normal UA and CMP. She did have a slightly elevated anticardiolipin antibody test, but a negative lupus anticoagulant test, the significance of which is uncertain. Her CRP and ESR were elevated.

Complete smoking cessation is essential for treatment

Several treatments have been proposed, including prostanoids and surgery (surgical revascularization or endovascular therapy).1,4 In severe cases, amputation may be required to remove the affected extremity. However, the most important and most effective treatment for TAO is smoking cessation.1 Of note, several case reports have found that replacing smoking with other nicotine-containing products (eg, chewing tobacco) may not prevent limb loss.7-9

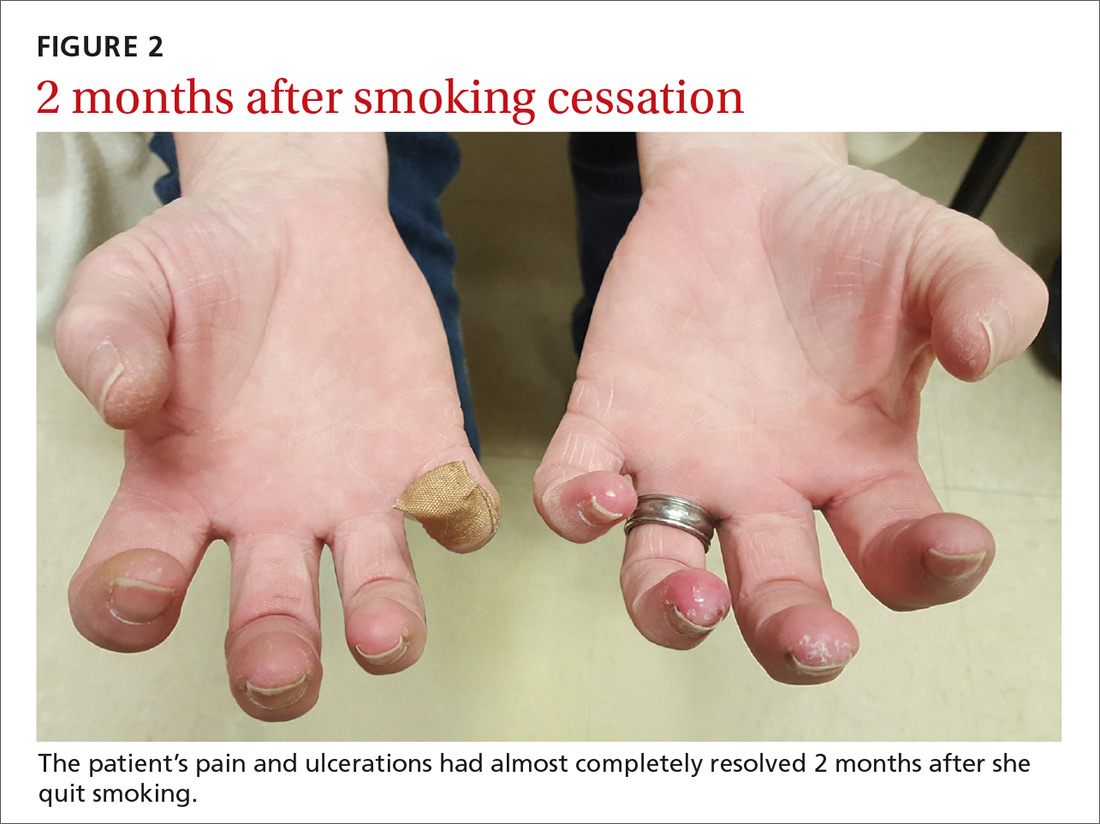

Our patient was tapered off prednisone and was continued on amlodipine 5 mg/d for vasospasm. She was started on varenicline 0.5 mg/d, which was increased to twice daily by Day 4 to aid with smoking cessation. Two months later, the patient’s pain and ulcerations had almost completely resolved (FIGURE 2). She experienced occasional relapses with smoking, during which her ulcerations and Raynaud’s would return. This case reinforces the age-old aphorism of “no tobacco, no Buerger’s disease.”4

CORRESPONDENCE

Seth Mathern, MD, 14300 Orchard Parkway, Westminster, CO 80023; Seth.Mathern@ucdenver.edu.