BALTIMORE – Given the prevalence of opioid use in the general population, sleep specialists need to be alert to the effects of opioid use on sleep and the link between chronic use and sleep disorders, a pulmonologist recommended at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Chronic opioid use has multiple effects on sleep that render continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) all but ineffective, said Bernardo J. Selim, MD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Characteristic signs of the effects of chronic opioid use on sleep include ataxic central sleep apnea (CSA) and sustained hypoxemia, for which CPAP is generally not effective. Obtaining arterial blood gas measures in these patients is also important to rule out a hypoventilative condition, he added.

In his review of opioid-induced sleep disorders, Dr. Selim cited a small “landmark” study of 24 chronic pain patients on opioids that found 46% had sleep disordered breathing and that the risk rose with the morphine equivalent dose they were taking (J Clin Sleep Med. 2014 Aug 15; 10[8]:847-52).

A meta-analysis also found a dose-dependent relationship with the severity of CSA in patients on opioids, Dr. Selim noted (Anesth Analg. 2015 Jun;120[6]:1273-85). The prevalence of CSA was 24% in the study, which defined two risk factors for CSA severity: a morphine equivalent dose exceeding 200 mg/day and a low or normal body mass index.

Dr. Selim noted that opioids reduce respiration rate more than tidal volume and cause changes to respiratory rhythm. “[Opioids] decrease hypercapnia but increase hypoxic ventilatory response, decrease the arousal index, decrease upper-airway muscle tone, and decrease and also act on chest and abdominal wall compliance.”

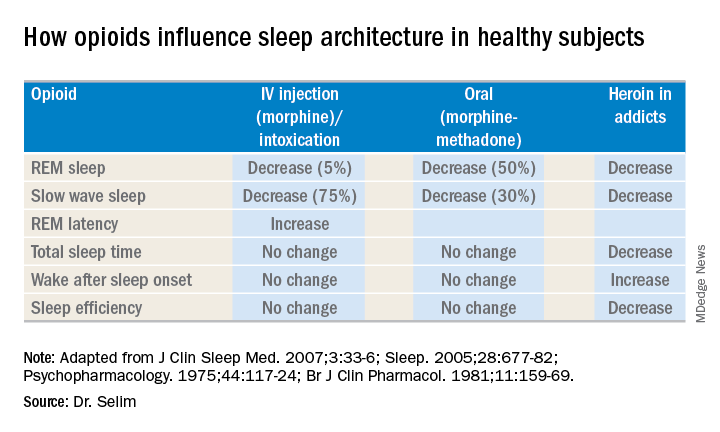

Further, different opioids and injection methods can influence breathing. For example, REM and slow-wave sleep decreased across all three categories – intravenous morphine, oral morphine or methadone, and heroin use.

Sleep specialists should be aware that all opioid receptor agonists, whether legal or illegal, have respiratory side effects, Dr. Selim said. “They can present in any way, in any form – CSA, obstructive sleep apnea [OSA], ataxic breathing or sustained hypoxemia. Most of the time [respiratory side effects] present as a combination of complex respiratory patterns.”

In one meta-analysis, CSA was significantly more prevalent in OSA patients on opioids than it was in nonusers, Dr. Selim said, with increased sleep apnea severity as well (J Clin Sleep Med. 2016 Apr 15;12[4]:617-25). Another study found that ataxic breathing was more frequent in non-REM sleep in chronic opioid users (odds ratio, 15.4; P = .017; J Clin Sleep Med. 2007 Aug 15;3[5]:455-61).

The key rule for treating sleep disorders in opioid-dependent patients is to change to nonopioid analgesics, Dr. Selim said. In that regard, ampakines are experimental drugs which have been shown to improve opioid-induced ventilation without loss of the analgesic effect (Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010 Feb;87[2]:204-11). “Ampakines modulate the action of the glutamate neurotransmitter, decreasing opiate-induced respiratory depression,” Dr. Selim said. An emerging technology, adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV), has been as effective in the treatment of central and complex sleep apnea in chronic opioid users as it is in patients with congestive heart failure, Dr. Selim said (J Clin Sleep Med. 2016 May 15;12[5]:757-61). “ASV can be very effective in these patients; lower body mass index being a predictor for ASV success,” he said.

Dr. Selim reported having no financial relationships.