THE CASE

A 37-year-old man presented with a sudden-onset, nonpruritic, nonpainful, papular rash of 1 month’s duration on his trunk and both arms and legs. Two weeks prior to the current presentation, he consulted a general practitioner, who treated the rash with a course of unknown oral antibiotics; the patient showed no improvement. He recalled that on a few occasions, he used his fingers to express a creamy discharge from some of the lesions. This temporarily reduced the size of those papules.

His medical history was unremarkable except for morbid obesity. He did not drink alcohol regularly and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the rash. He had no family history of hyperlipidemia, but his mother had a history of diabetes mellitus.

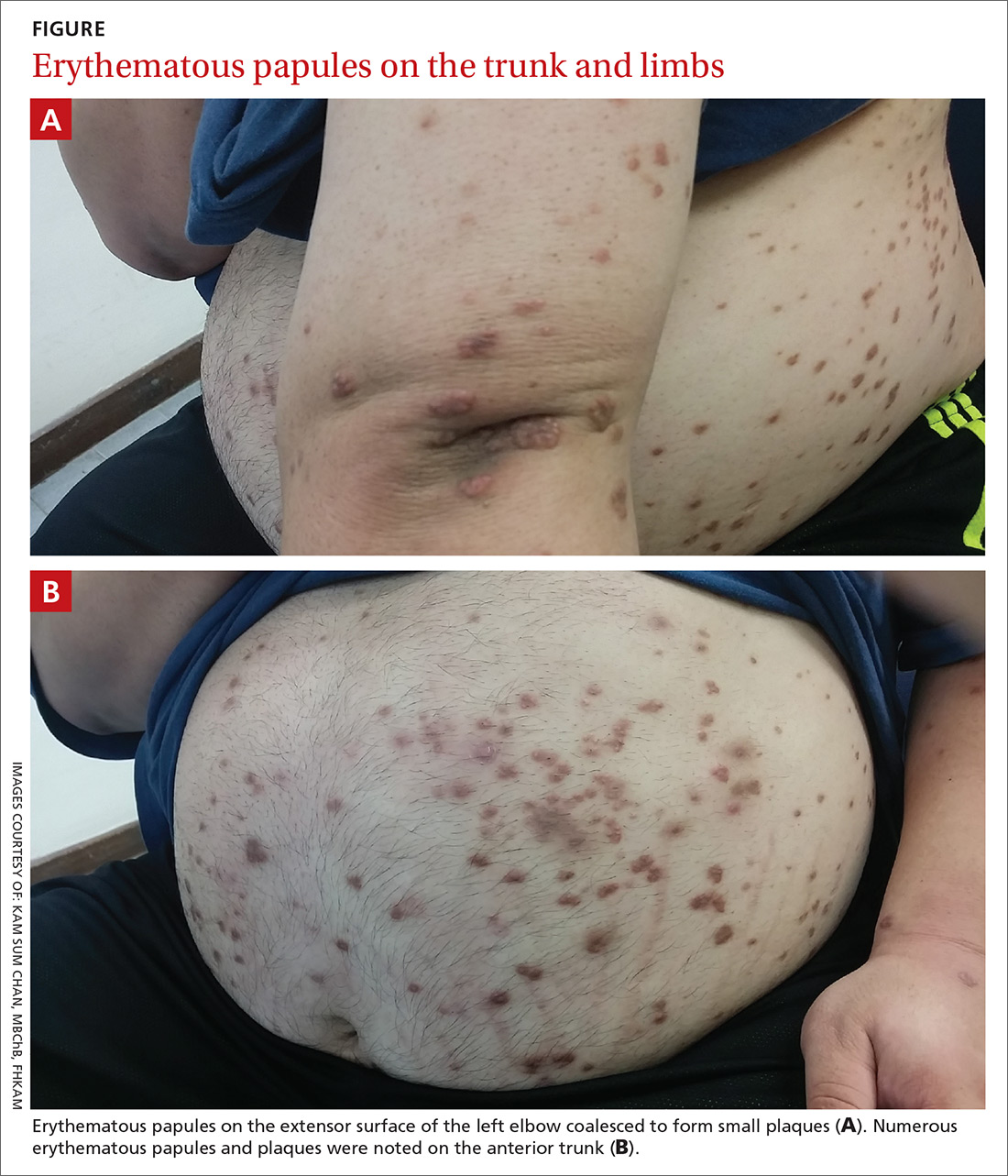

Physical examination showed numerous discrete erythematous papules with a creamy center on his trunk and his arms and legs. The lesions were more numerous on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. Some of the papules coalesced to form small plaques (FIGURE). There was no scaling, and the lesions were firm in texture. The patient’s face was spared, and there was no mucosal involvement. The patient was otherwise systemically well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the morphology, distribution, and abrupt onset of the diffuse nonpruritic papules in this morbidly obese (but otherwise systemically well) middle-aged man, a clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma was suspected. Subsequent blood testing revealed an elevated serum triglyceride level of 47.8 mmol/L (reference range, <1.7 mmol/L), elevated serum total cholesterol of 7.1 mmol/L (reference range, <6.2 mmol/L), and low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol of 0.7 mmol/L (reference range, >1 mmol/L in men). He also had an elevated fasting serum glucose level of 12.9 mmol/L (reference range, 3.9–5.6 mmol/L) and an elevated hemoglobin A1c (glycated hemoglobin) level of 10.9%.

Subsequent thyroid, liver, and renal function tests were normal, but the patient had heavy proteinuria, with an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 355.6 mg/mmol (reference range, ≤2.5 mg/mmol). The patient was referred to a dermatologist, who confirmed the clinical diagnosis without the need for a skin biopsy.

DISCUSSION

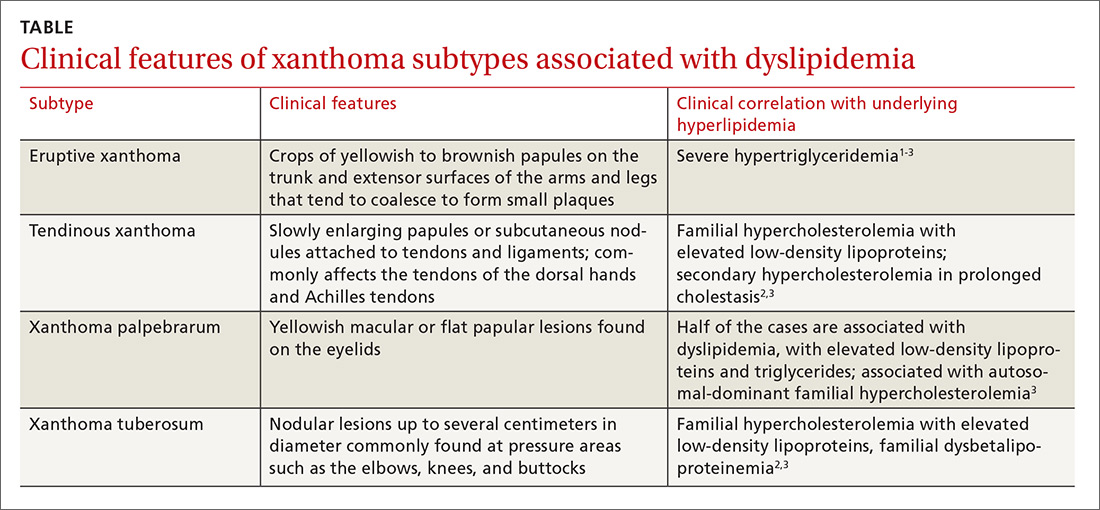

Xanthomas are lipid deposits in the skin and subcutaneous tissues that arise in the setting of hyperlipidemia and are caused by underlying familial or acquired disorders. Xanthomas associated with dyslipidemias include eruptive xanthoma, tendinous xanthoma, xanthoma palpebrarum, and xanthoma tuberosum (TABLE).1-3 Other non–dyslipidemia-related xanthomas include xanthoma planum, xanthoma disseminatum, linear palmar xanthomas, and verrucous xanthoma. One retrospective cohort study reported an 8.5% (8/95) prevalence of eruptive xanthomas in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia (ie, triglyceride levels >1770 mg/dL).4 Data on the prevalence of other variants of xanthoma are lacking.

Eruptive xanthoma is characterized by an abrupt onset of crops of multiple yellowish to brownish papules that can coalesce into small plaques. The lesions can be generalized, but tend to be more densely distributed on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, buttocks, and thighs.5 Eruptive xanthoma often is associated with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be primary—as a result of a genetic defect caused by familial hypertriglyceridemia—or secondary, associated with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, primary biliary cholangitis, and drugs like estrogen replacement therapies, corticosteroids, and isotretinoin.6 Pruritus and tenderness may or may not be present, and the Köbner phenomenon may occur.7

Continue to: The differential diagnosis