Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious public health problem with considerable harmful health consequences. Decades of research have been dedicated to improving the identification of women in abusive heterosexual relationships and interventions that support healthier outcomes. A result of this work has been the recommendation of the US Preventive Services Task Force that all women of childbearing age be screened for IPV and provided with intervention or referral.1

The problem extends further, however: Epidemiologic studies and comprehensive reviews show: 1) a high rate of IPV victimization among heterosexual men and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transsexual (LGBT) men and women2,3; 2) significant harmful effects on health and greater expectations of prejudice and discrimination among these populations4-6; and 3) evidence that screening and referral for IPV are likely to confer similar benefits for these populations.7 We argue that it is reasonable to ask all patients about abuse in their relationships while the research literature progresses.

We intend this article to serve a number of purposes:

- support national standards for IPV screening of female patients

- highlight the need for piloting universal IPV screening for all patients (ie, male and female, across the lifespan)

- offer recommendations for navigating the process from IPV screening to referral, using insights gained from the substance abuse literature.

We also provide supplemental materials that facilitate establishment of screening and referral protocols for physicians across practice settings.

What is intimate partner violence? How can you identify it?

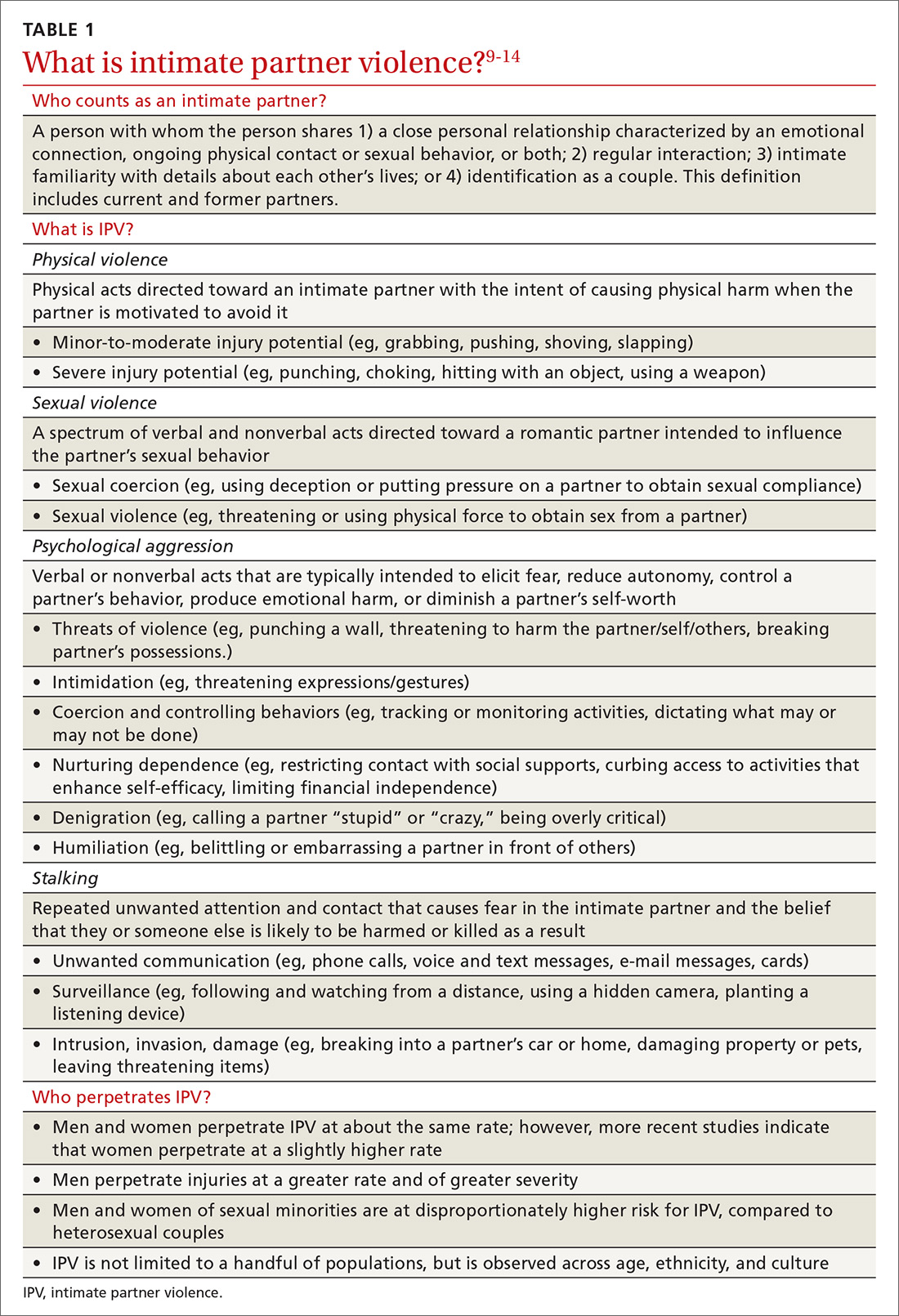

Intimate partner violence includes physical and sexual violence and nonphysical forms of abuse, such as psychological aggression and emotional abuse, perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner.8 TABLE 19-14 provides definitions for each of these behavior categories and example behaviors. Nearly 25% of women and 20% of men report having experienced physical violence from a romantic partner and even higher rates of nonphysical IPV.15 Consequences of IPV victimization include acute and chronic medical illness, injury, and psychological problems, including depression, anxiety, and poor self-esteem.16

Intimate partner violence is heterogeneous, with differences in severity (eg, frequency and intensity of violence) and laterality (ie, is one partner violent? are both partners violent?). A recent comprehensive review of the literature revealed that, for 49.2%-69.7% of partner-violent couples across diverse samples, IPV is perpetrated by both partners.17 Furthermore, this bidirectionality is not due entirely to aggression perpetrated in self-defense; rather, across diverse patient samples, that is the case for fewer than one-quarter of males and no more than approximately one-third of females.18 In the remaining cases, bidirectionality may be attributed to other motivations, such as a maladaptive emotional expression or a means by which to get a partner’s attention.18

Women are disproportionately susceptible to harmful outcomes as a result of severe violence, including physical injury, psychological distress (eg, depression and anxiety), and substance abuse.16,19 Some patients in unidirectionally violent relationships experience severe physical violence that may be, or become, life-threatening (0.4%-2.4% of couples in community samples)20—victimization that is traditionally known as “battering.”21

Continue to: These tools can facilitate screening for IPV