In 2017, the Australian state of New South Wales experienced an outbreak of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children despite a high level of rotavirus immunization. In a new study, researchers reported evidence that suggests a decline in vaccine effectiveness (VE) isn’t the cause, although they found that VE declines over time as children age.

“More analysis is required to investigate how novel or unusual strains ... interact with rotavirus vaccines and whether antigenic changes affect VE and challenge vaccination programs,” the study authors wrote in Pediatrics.

Researchers led by Julia E. Maguire, BSc, MSci(Epi), of Australia’s National Center for Immunization Research and the Australian National University, Canberra, launched the analysis in the wake of a 2017 outbreak of 2,319 rotavirus cases in New South Wales, a 210% increase over the rate in 2016. (The state, the largest in Australia, has about 7.5 million residents.)

The study authors tracked VE from 2010 to 2017 by analyzing 9,517 rotavirus cases in the state (50% male; median age, 5 years). Half weren’t eligible for rotavirus immunization because of their age; of the rest, 31% weren’t vaccinated.

Ms. Maguire and associates found that “In our study, two doses of RV1 [the Rotarix vaccine] was 73.7% effective in protecting children aged 6 months to 9 years against laboratory-confirmed rotavirus over our 8-year study period. Somewhat surprisingly in the 2017 outbreak year, a high two-dose VE of 88.4% in those aged 6-11 months was also observed.”

They added that “the median age of rotavirus cases has increased in Australia over the last 8 years from 3.9 years in 2010 to 7.1 years in 2017. Adults and older children born before the availability of vaccination in Australia are unimmunized and may have been less likely to have repeated subclinical infections because of reductions in virus circulation overall, resulting in less immune boosting.”

Going forward, the study authors wrote that “investigation of population-level VE in relation to rotavirus genotype data should continue in a range of settings to improve our understanding of rotavirus vaccines and the impact they have on disease across the age spectrum over time.”

In an accompanying commentary, Benjamin Lee, MD, and E. Ross Colgate, PhD, of the University of Vermont, Burlington, wrote that Australia’s adoption of rotavirus immunization in 2017 “with state-level implementation of either Rotarix or RotaTeq ... enabled a fascinating natural experiment of VE and strain selection.”

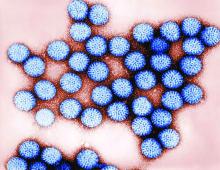

Pressure from vaccines “potentially enables the emergence of novel strains,” they wrote. “Despite this, large-scale strain replacement has not been demonstrated in rotaviruses, in contrast to the development of pneumococcal serotype replacement that was seen after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction. Similarly, there has been no evidence of widespread vaccine escape due to antigenic drift or shift, as occurs with another important segmented RNA virus, influenza A.”

As Dr. Lee and Dr. Colgate noted, 100 million children worldwide remain unvaccinated against rotavirus, and more than 128,000 die because of rotavirus-associated gastroenteritis each year. “Improving vaccine access and coverage and solving the riddle of [oral rotavirus vaccine] underperformance in low-income countries are urgent priorities, which may ultimately require next-generation oral and/or parenteral vaccines, a number of which are under development and in clinical trials. In addition, because the emergence of novel strains of disease-causing pathogens is always a possibility, vigilance in rotavirus surveillance, including genotype assessment, should remain a priority for public health programs.”

The study was funded by Australia’s National Center for Immunization Research and Surveillance, which receives government funding. The Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program is supported by government funding and the vaccine companies Commonwealth Serum Laboratories and GlaxoSmithKline. Ms. Maguire is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. One author is director of the Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program, which received funding as above. The other study authors and the commentary authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Maguire JE et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1024; Lee B, Colgate ER. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2426.