During assessment, we must adopt the means to identify the reason that a patient is using a prescription opioid. It is of particular importance that we identify patients using opioids for their psychotropic properties, particularly when the goal is to cope with the effects of psychological trauma. The subsequent treatment protocol will then need to include time for effective, evidence-based behavioral health treatment of anxiety, PTSD, or depression. If opioids are serving primarily as psychotropic medication, an attempt to taper before establishing effective behavioral health treatment might lead the patient to pursue illegal means of procuring opioid medication.

We acknowledge that primary care physicians are not reimbursed for trauma screening and that evidence-based intensive trauma treatment is generally unavailable in the United States. Both of these shortcomings must be corrected if we want to stem the opioid crisis.

If diversion is suspected and there is evidence that the patient is not currently taking prescribed opioids (eg, a negative urine drug screen), discontinuing the opioid prescription is the immediate next step for the sake of public safety.

SIDEBAR

2 decisions to make before continuing to prescribe an opioid for chronic noncancer pain

#1 Should I provide the patient with a prescription for an opioid for a few days, while I await more information?a

Yes. Writing a prescription is a reasonable decision if all of the following apply:

- You do not have significant suspicion of diversion (based on a clinical interview).

- You do not suspect an active addiction disorder, based on the score of the 10-question Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) and on a clinical interview. (DAST-10 is available at: https://cde.drugabuse.gov/instrument/e9053390-ee9c-9140-e040-bb89ad433d69.)

- The patient is likely to experience withdrawal symptoms if you don’t provide the medication immediately.

- The patient’s pain and function are likely to be impaired if you do not provide the medication.

- The patient does not display altered mental status during the visit (eg, drowsy, slurred speech).

No. If writing a prescription for an opioid for a few days does not seem to be a reasonable decision because the criteria above are not met, but withdrawal symptoms are likely, you can prescribe medication to mitigate symptoms or refer the patient for treatment of withdrawal.

#2 I’ve decided to provide the patient with a prescription for an opioid. For how many days should I write it?

The usual practice, for a patient whose case is familiar to you, is to prescribe a 1-month supply.

However, if any 1 of the following criteria is met, prescribing a 1-month supply is unsafe under most circumstances:

- An unstable social or living environment places the patient at risk by possessing a supply of opioids (based on a clinical interview).

- You suspect an unstable or severe behavioral health condition or a mental health diagnosis (based on a clinical interview or on the patient record from outside your practice).

- The patient scores as “high risk” on the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT; www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/OpioidRiskTool.pdf), Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4706778/), or a similar opioid risk assessment tool.

When 1 or more of these exclusionary criteria are met, you have 3 options:

- Prescribe an opioid for a brief duration and see the patient often.

- Do not prescribe an opioid; instead, refer the patient as necessary for treatment of withdrawal.

- Refer the patient for treatment of the underlying behavioral health condition.

a Additional information might include findings from consultants you’ve engaged regarding the patient’s diagnosis; a response to your call from a past prescriber; urine drug screen results; and results of a prescription monitoring program check.

Considering a taper? Take this 5-step approach

Once it appears that tapering an opioid is indicated, we propose that you take the following steps:

- Establish whether it is safe to continue prescribing (follow the route provided in “2 decisions to make before continuing to prescribe an opioid for chronic noncancer pain”); if continuing it is not safe, take steps to protect the patient and the community

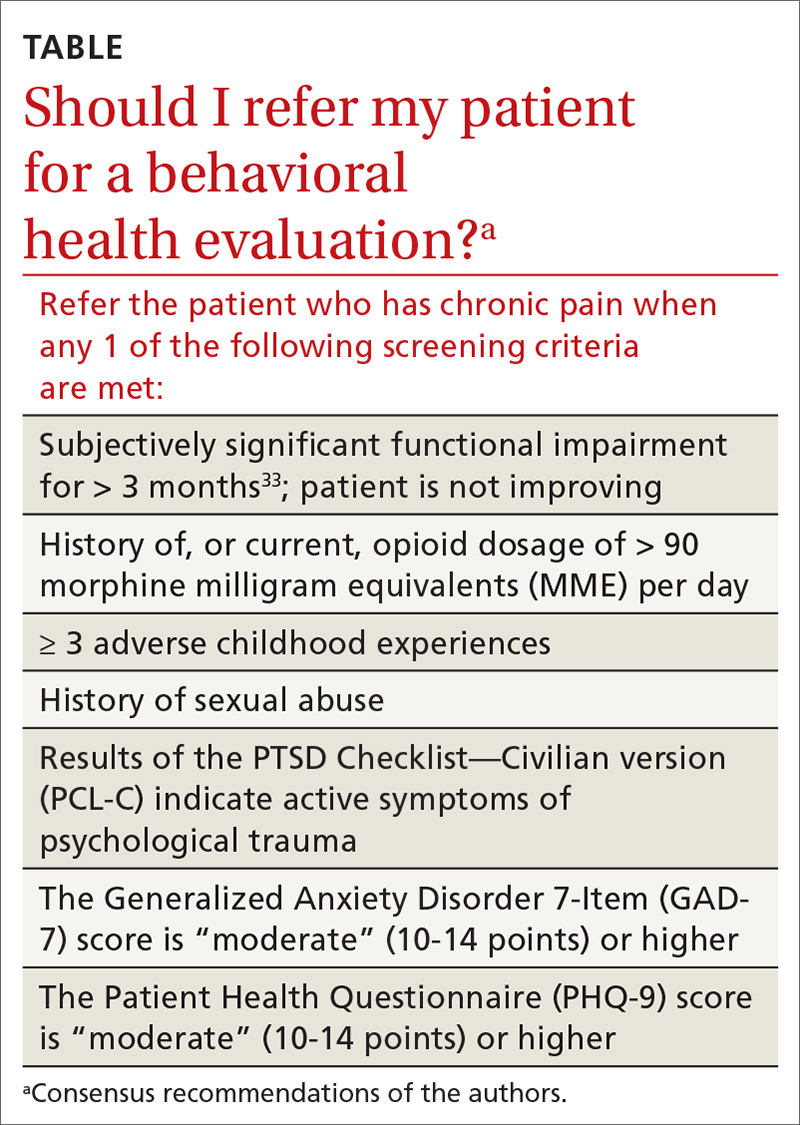

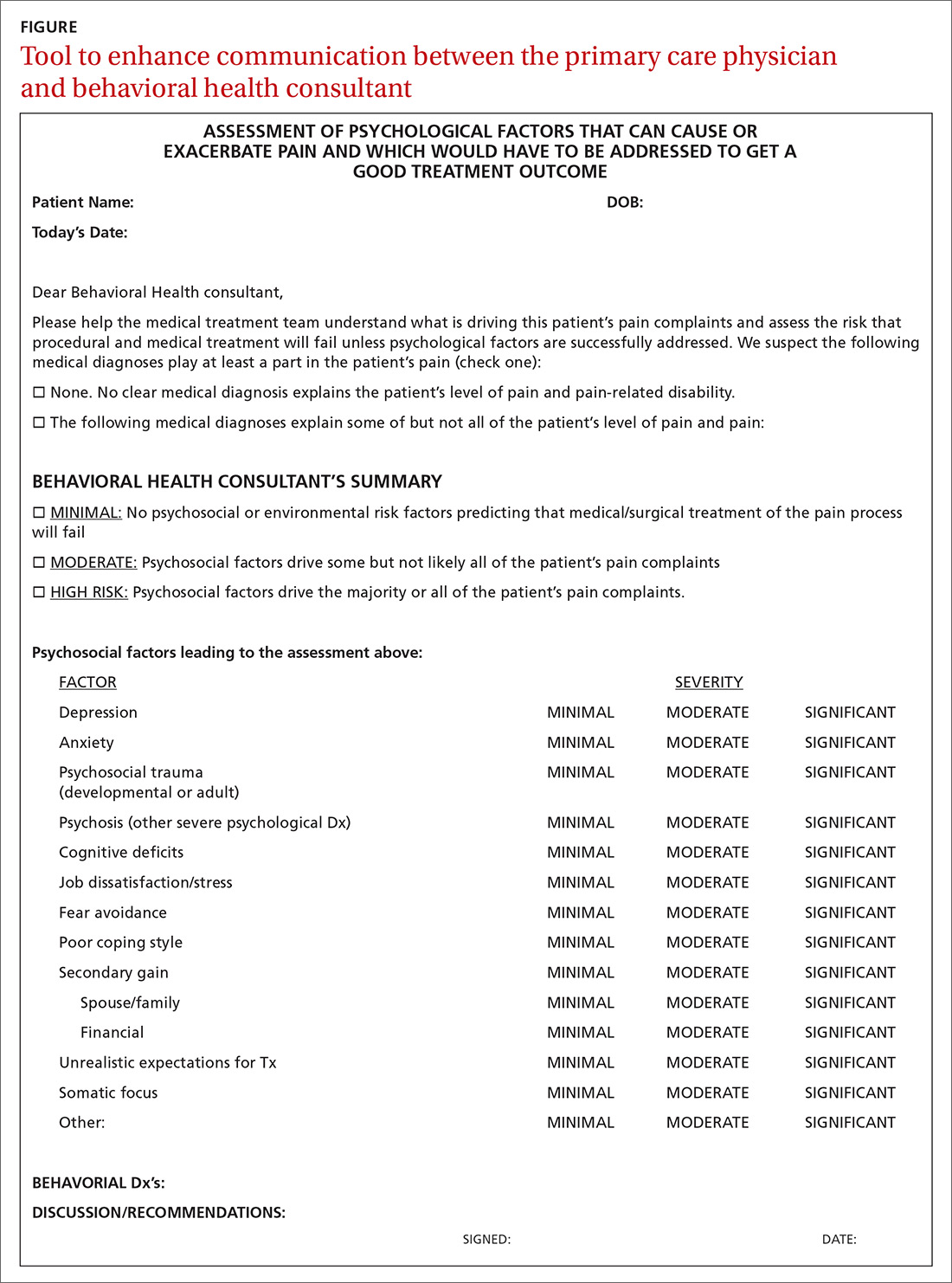

- Determine whether assessment by a trauma-informed behavioral health expert is needed, assuming that, in your judgment, it is safe to continue the opioid (TABLE33). When behavioral health assessment is needed, you need 3 questions answered by that assessment: (1) Are psychological factors present that might put the patient at risk during an opioid taper? (2) What are those factors? (3) What needs to done about them before the taper is started? Recalling that psychological trauma often is not assessed by behavioral health colleagues, it is necessary to provide the behavioral health provider with a specific request to assess trauma burden, and state the physical diagnoses that are causing pain or provide a clear statement that no such diagnoses can be made. (See the FIGURE, which we developed in conjunction with behavioral health colleagues to help the consultant understand what the primary care physician needs from a behavioral health assessment.)

- Obtain consultation from a physical therapist, pain medicine specialist, and, if possible, an alternative or complementary medicine provider to determine what nonpharmacotherapeutic modalities can be instituted to treat pain before tapering the opioid.

- Initiate the Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) approach if OUD is suspected (www.samhsa.gov/sbirt).34 This motivational interviewing tool identifies patients with a substance use disorder, severity of use, and appropriate level of treatment. (If OUD is suspected during assessment, next steps are to stop prescribing and implement harm-reduction strategies, such as primary care level medically assisted treatment [MAT] with buprenorphine, followed by expert behavioral health-centered addiction treatment.)

- Experiment with dosage reduction according to published guidance, if (1) psychological factors are absent or have been adequately addressed, according to the behavioral health consultant, and (2) nonpharmacotherapeutic strategies are in place.8-11

Shifting to a patient-centered approach

The timing and choice of opioid tapers, in relation to harm reduction and intervention targeting the root cause of a patient’s complaint of pain, have not been adequately explored. In our practice, we’ve shifted from an addiction-centered, dosage-centered approach to opioid taper to a patient-centered approach35 that emphasizes behavioral-medical integration—an approach that we broadly endorse. Such an approach (1) is based on a clear understanding of why the patient is taking opioid pain medication, (2) engages medical and complementary or alternative medicine specialists, (3) addresses underdiagnosis of psychological trauma, and (4) requires a quantum leap in access to trauma-specific behavioral health treatment resources. 36

Continue to: To underscore the case...