Food allergy is a complex condition that has become a growing concern for parents and an increasing public health problem in the United States. Food allergy affects social interactions, school attendance, and quality of life, especially when associated with comorbid atopic conditions such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis.1,2 It is the major cause of anaphylaxis in children, accounting for as many as 81% of cases.3 Societal costs of food allergy are great and are spread broadly across the health care system and the family. (See “What is the cost of food allergy?”2.)

SIDEBAR

What is the cost of food allergy?

Direct costs of food allergy to the health care system include medications, laboratory tests, office visits to primary care physicians and specialists, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations. Indirect costs include family medical and nonmedical expenses, lost work productivity, and job opportunity costs. Overall, the cost of food allergy in the United States is $24.8 billion annually—averaging $4184 for each affected child. Parents bear much of this expense.2

What a food allergy is—and isn’t

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) defines food allergy as “an adverse health effect arising from a specific immune response that occurs reproducibly on exposure to a given food.”4 An adverse reaction to food or a food component that lacks an identified immunologic pathophysiology is not considered food allergy but is classified as food intolerance.4

Food allergy is caused by either immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated or non-IgE-mediated immunologic dysfunction. IgE antibodies can trigger an intense inflammatory response to certain allergens. Non-IgE-mediated food allergies are less common and not well understood.

This article focuses only on the diagnosis and management of IgE-mediated food allergy.

The culprits

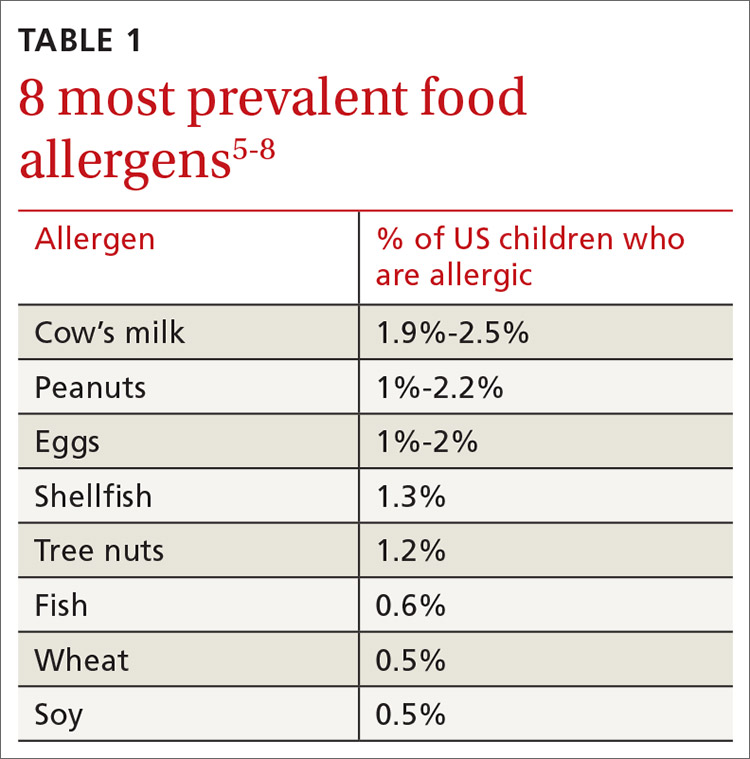

More than 170 foods have been reported to cause an IgE-mediated reaction. Table 15-8 lists the 8 foods that most commonly cause allergic reactions in the United States and that account for > 50% of allergies to food.9 Studies vary in their methodology for estimating the prevalence of allergy to individual foods, but cow’s milk and peanuts appear to be the most common, each affecting as many as 2% to 2.5% of children.7,8 In general, allergies to cow’s milk and to eggs are more prevalent in very young and preschool children, whereas allergies to peanuts, tree nuts, fish, and shellfish are more prevalent in older children.10 Labels on all packaged foods regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration must declare if the product contains even a trace of these 8 allergens.

How common is food allergy?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 4% to 6% of children in the United States have a food allergy.11,12 Almost 40% of food-allergic children have a history of severe food-induced reactions.13 Other developed countries cite similar estimates of overall prevalence.14,15

However, many estimates of the prevalence of food allergy are derived from self-reports, without objective data.9 Accurate evaluation of the prevalence of food allergy is challenging because of many factors, including differences in study methodology and the definition of allergy, geographic variation, racial and ethnic variations, and dietary exposure. Parents and children often confuse nonallergic food reactions, such as food intolerance, with food allergy. Precise determination of the prevalence and natural history of food allergy at the population level requires confirmatory oral food challenges of a representative sample of infants and young children with presumed food allergy.16

Continue to: The CDC concludes that the prevalence...