A new monograph offers a far-reaching update on research and clinical management of bipolar disorders (BDs), including epidemiology, genetics, pathogenesis, psychosocial aspects, and current and investigational therapies.

“I regard this as a ‘global state-of-the-union’ type of paper designed to bring the world up to speed regarding where we’re at and where we’re going in terms of bipolar disorder, to present the changes on the scientific and clinical fronts, and to open up a global conversation about bipolar disorder,” lead author Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, told Medscape Medical News.

“The paper is oriented toward multidisciplinary care, with particular emphasis on primary care, as well as people in healthcare administration and policy, who want a snapshot of where we’re at,” said McIntyre, who is also the head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit and director of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance in Chicago, Illinois.

The article was published online December 5 in The Lancet.

Severe, complex

The authors call BPs “a complex group of severe and chronic disorders” that include both BP I and BP II disorders.

“These disorders continue to be the world’s leading causes of disability, morbidity, and mortality, which are significant and getting worse, with studies indicating that bipolar disorders are associated with a loss of roughly 10 to 20 potential years of life,” McIntyre said.

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of premature death in people with BD. The second is suicide, the authors state, noting that patients with BDs are roughly 20-30 times more likely to die by suicide compared with the general population. In addition, 30%-50% have a lifetime history of suicide attempts.

BP I is “defined by the presence of a syndromal manic episode,” while BP II is “defined by the presence of a syndromal hypomanic episode and a major depressive episode,” the authors state.

Unlike the DSM-IV-TR, the DSM-5 includes “persistently increased energy or activity, along with elevated, expansive, or irritable mood” in the diagnostic criteria for mania and hypomania, “so diagnosing mania on mood instability alone is no longer sufficient,” the authors note.

In addition, clinicians “should be aware that individuals with BDs presenting with depression will often manifest symptoms of anxiety, agitation, anger-irritability, and attentional disturbance-distractibility (the four A’s), all of which are highly suggestive of mixed features,” they write.

Depression is the “predominant index presentation of BD” and “differentiating BD from major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most common clinical challenge for most clinicians.”

Features suggesting a diagnosis of BD rather than MDD include earlier age of onset, phenomenology (e.g., hyperphagia, hypersomnia, psychosis), higher frequency of affective episodes, comorbidities (e.g., substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, binge eating disorders, and migraines), family history of psychopathology, nonresponse to antidepressants or induction of hypomania, mixed features, and comorbidities

The authors advise “routine and systematic screening for BDs in all patients presenting with depressive symptomatology” and recommend using the Mood Disorders Questionnaire and the Hypomania Checklist.

Additional differential diagnoses include psychiatric disorders involving impulsivity, affective instability, anxiety, cognitive disorganization, depression, and psychosis.

“Futuristic” technology

“Although the pathogenesis of BDs is unknown, approximately 70% of the risk for BDs is heritable,” the authors note. They review recent research into genetic loci associated with BDs, based on genome-wide association studies, and the role of genetics not only in BDs but also in overlapping neurologic and psychiatric conditions, insulin resistance, and endocannabinoid signaling.

Inflammatory disturbances may also be implicated, in part related to “lifestyle and environment exposures” common in BDs such as smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity, and trauma, they suggest.

An “exciting new technology” analyzing “pluripotent” stem cells might illuminate the pathogenesis of BDs and mechanism of action of treatments by shedding light on mitochondrial dysfunction, McIntyre said.

“This interest in stem cells might almost be seen as futuristic. It is currently being used in the laboratory to understand the biology of BD, and it may eventually lead to the development of new therapeutics,” he added.

“Exciting” treatments

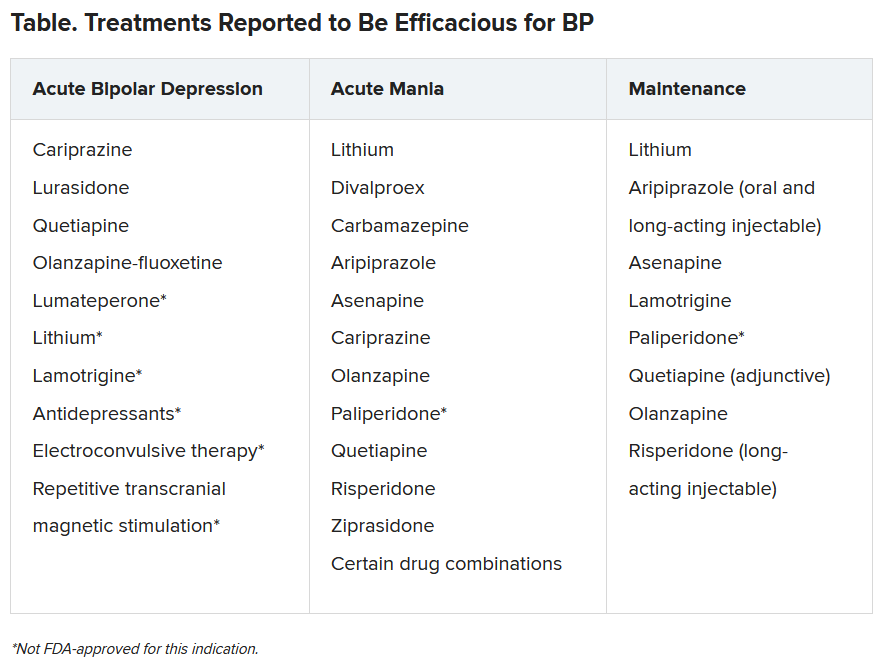

“Our expansive list of treatments and soon-to-be new treatments is very exciting,” said McIntyre.

The authors highlight “ongoing controversy regarding the safe and appropriate use of antidepressants in BD,” cautioning against potential treatment-emergent hypomania and suggesting limited circumstances when antidepressants might be administered.

Lithium remains the “gold standard mood-stabilizing agent” and is “capable of reducing suicidality,” they note.

Nonpharmacologic interventions include patient self-management, compliance, and cognitive enhancement strategies, primary prevention for psychiatric and medical comorbidity, psychosocial treatments and lifestyle interventions during maintenance, as well as surveillance for suicidality during both acute and maintenance phases.

Novel potential treatments include coenzyme Q10, N-acetyl cysteine, statins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, omega-3 fatty acids, incretin-based therapies, insulin, nitrous oxide, ketamine, prebiotics, probiotics, antibiotics, and adjunctive bright light therapy.

The authors caution that these investigational agents “cannot be considered efficacious or safe” in the treatment of BDs at present.

Call to action

Commenting for Medscape Medical News, Michael Thase, MD, professor of psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said he is glad that this “stellar group of authors” with “worldwide psychiatric expertise” wrote the article and he hopes it “gets the readership it deserves.”

Thase, who was not an author, said, “One takeaway is that BDs together comprise one of the world’s great public health problems — probably within the top 10.”

Another “has to do with our ability to do more with the tools we have — ie, ensuring diagnosis, implementing treatment, engaging social support, and using proven therapies from both psychopharmacologic and psychosocial domains.”

McIntyre characterized the article as a “public health call to action, incorporating screening, interesting neurobiological insights, an extensive set of treatments, and cool technological capabilities for the future.”

McIntyre has reported receiving grant support from the Stanley Medical Research Institute and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Global Alliance for Chronic Disease/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation, and speaker fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Shire, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Intra-Cellular, Alkermes, and Minerva, and is chief executive officer of Champignon. Disclosures for the other authors are listed in the article. Thase has reported consulting with and receiving research funding from many of the companies that manufacture/sell antidepressants and antipsychotics. He also has reported receiving royalties from the American Psychiatric Press Incorporated, Guilford Publications, Herald House, and W.W. Norton & Company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.