results of the first prospective study of the subject revealed.

The main message for health care workers is, “if you’ve had COVID, at least in the short term, you are unlikely to get it again,” David Eyre, DPhil, senior author, associate professor at the Big Data Institute and infectious diseases clinician at the University of Oxford (England), said in an interview.

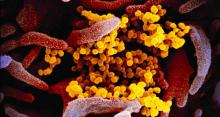

Dr. Eyre and colleagues assessed for the presence of two antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 among 12,541 health care workers in the United Kingdom, including about 10% who had a history of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–confirmed infection. Of those, 223 who did not have antibodies tested positive on PCR for the virus during 31 weeks of follow-up; two participants who did not have antibodies at baseline tested positive.

The study was published online Dec. 23 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“It’s great news because there have been so many questions regarding whether or not you can be protected against reinfection, and this health care worker study is really an elegant way to address that question,” Mark Slifka, PhD, said in an interview when asked to comment on the findings.

Although “there are millions of people in the U.S. who have been infected with COVID, we don’t know how common reinfection is,” said Dr. Slifka, a researcher at the Oregon National Primate Research Center and professor at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

The likelihood of a subsequent positive PCR test result was 1.09 per 10,000 days at risk among those without antibodies, compared with 0.13 per 10,000 days among those with anti-spike antibodies.

The investigators also assessed for the presence of anti–nucleocapsid IgG antibody titers. They found a significant trend for increasing PCR-positive test results with increasing antibody levels. As with the anti-spike antibody findings, 226 of 11,543 health care providers who did not have anti–nucleocapsid IgG antibodies subsequently tested positive on PCR; by contrast, two of 1,172 participants who did not have antibodies tested positive. Adjusted for age, sex, and calendar time, this finding translates to a 0.11 incidence rate ratio (0.13 per 10,000 days at risk; 95% confidence interval, 0.03-0.45; P = .002).

“This is a study a number of us have been trying to do,” said Christopher L. King, MD, PhD, professor of pathology and associate professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

“To really follow a group like this longitudinally like they’ve done, with a large population, and to see such a big difference – it really confirms our suspicion that those who do become infected and develop an antibody response are significantly protected from reinfection.

“What’s great about this study is it’s nearly a 10-fold reduction in risk if you’ve recovered from COVID and have antibodies,” said Dr. King, who was not involved with the research. “That’s what a lot of us have been wanting to know.”