Atopic dermatitis (AD), also known as eczema, is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that is well known for its relapsing, pruritic rash in children and adults. Less recognized are its associated conditions—allergic rhinitis, asthma, food allergies, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, and anxiety—and its burden on patients and their families. In fact, families that have children with AD report lower overall quality of life than those with otherwise healthy children.1 Given AD’s prevalence across age groups and its effect on the family, family physicians are uniquely positioned to diagnose, care for, and counsel patients with AD and its associated maladies.

The prevalence and pathogenesis of AD

AD affects up to 20% of children and 5% of adults in the United States.2 AD typically manifests before a child reaches age 5 (often in the first 6 months of life), and it is slightly more common in females (1.3:1). A family history of atopy (eczema, asthma, allergic rhinitis) is common. In fact, children with one atopic parent have a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of atopic dermatitis; those with 2 atopic parents have a 3- to 5-fold increased risk.3

The pathophysiology of AD is complex, culminating in impaired barrier function of the skin and transepidermal water loss resulting in dry and inflamed skin. Additionally, alterations in a cell-mediated immune response leading to an immunoglobulin (Ig) E-mediated hypersensitivity is also theorized to play a role in the development of AD.

Signs and symptoms

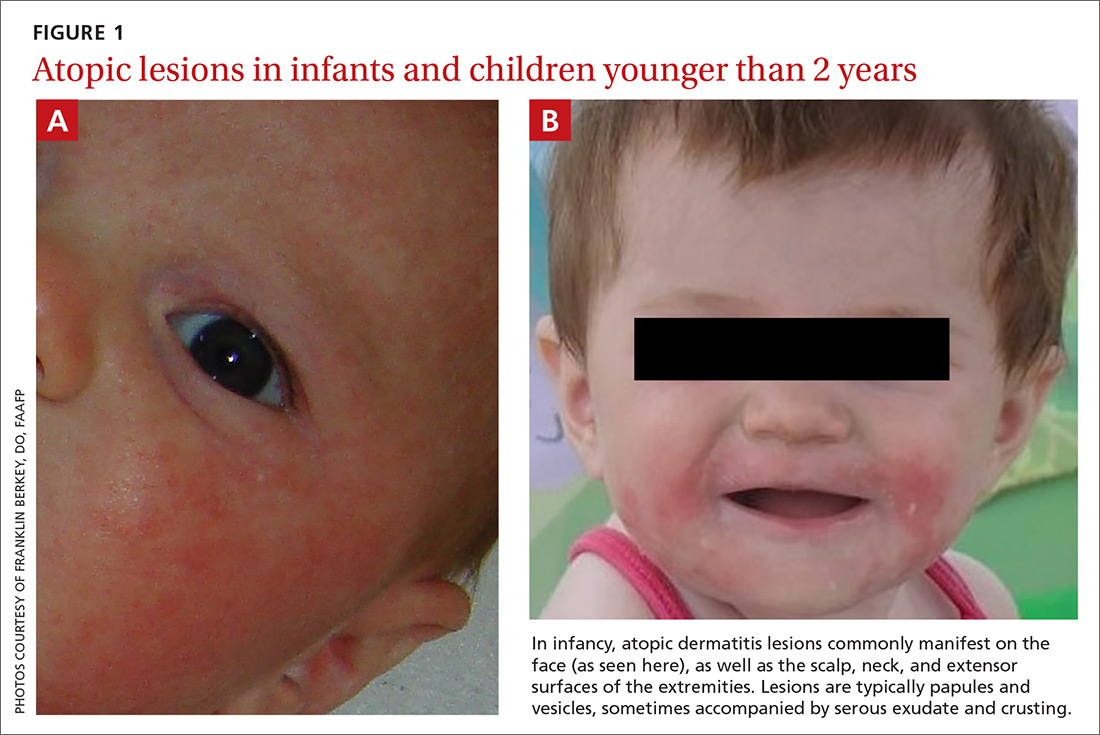

Signs at birth. Physical signs of atopic dermatitis typically appear between birth and 6 months. In infancy, lesions generally occur on the scalp, face (FIGURES 1A and 1B), neck, and extensor surfaces of the extremities. Lesions are typically papules and vesicles, sometimes accompanied by serous exudate and crusting. Eczematous lesions typically spare the groin and diaper area, and their presence in this area should raise suspicion for an alternative diagnosis.

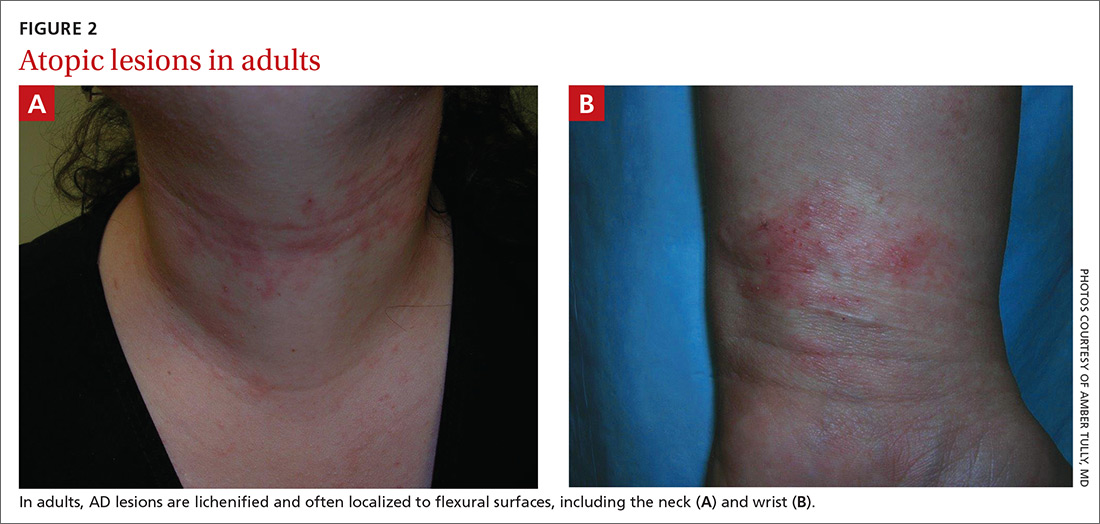

Beginning at age 2 years, eczematous lesions are more commonly limited to the folds of the flexor surfaces. Instead of the weeping and crusting lesions seen in infancy, eczema in older children manifests as dry, lichenified papules and plaques in areas that are typically affected in adults: the wrist, hands, ankles, and popliteal and antecubital fossa.2

Although lesions in adults are similar to those of childhood, they may manifest in a more localized area (hand or eyelid, for example). As is the case in childhood, the lesions are dry, sometimes lichenified, and found on the flexural surfaces (FIGURES 2A and 2B).2

Symptom triggers are unproven

While anecdotal reports cite various triggers for AD flares, a systematic review found little scientific evidence to substantiate identifiable triggers.4 Triggers often cited and studied are foods, dust mite exposure, airborne allergens, detergents, sunlight, fabrics, bacterial infections, and stress. While as many as one-third of people with AD who also have confirmed dust mite allergy report worsening of symptoms when exposed to dust, a Cochrane review of 7 randomized controlled trials totaling 324 adults and children with eczema found that efforts at dust mite mitigation (laundering of bed covers, increased vacuuming, spraying for mites) were not effective in reducing symptoms.5

Continue to: How quality of life diminishes with AD