NEW ORLEANS – Hypertensive patients with persistent left ventricular hypertrophy despite normalized blood pressure faced a substantially higher risk for death and cardiovascular events, compared with patients without hypertrophy on antihypertensive treatment, according to the findings of a study involving 463 patients.

"These results suggest that persistence of left ventricular hypertrophy in a subset of patients with lower achieved blood pressure during treatment may in part explain the lack of benefit seen in hypertensive patients, despite treatment to lower systolic blood pressure," Dr. Peter M. Okin said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Based on these results, it may be necessary to track end-organ damage – in this case, as manifested by ECG left ventricular hypertrophy – in addition to blood pressure to fully assess response to treatment in hypertensive patients. "You can’t just track blood pressure; you need to look at end-organ damage," such as the size of the heart, said Dr. Okin, a cardiologist and professor of medicine at Cornell University in New York.

But currently no evidence exists on the best way to manage patients whose hearts remain enlarged despite blood pressure normalization.

"The data are not there to say you should treat these patients more aggressively," he said in an interview. In fact, an equally plausible approach would be to back off treatment in such patients because of the high hazard they face and the lack of evidence that treatment helps their clinical outcome. Randomized trials must be done to identify the best way to manage these patients, he said.

The analysis Dr. Okin reported came from a subset of patients who were enrolled in the LIFE (Losartan Intervention for End Point Reduction in Hypertension) study, which enrolled 9,193 patients aged 55-80 years with a blood pressure of 160/95 mm Hg to 200/115 mm Hg. The study randomized patients to two different antihypertensive treatment arms, one based primarily on losartan and the control based primarily on atenolol, with a target blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or less (Lancet 2002;359:995-1003).

The subgroup that was used for the new analysis included the 463 patients in the study who achieved a systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less. Their average age was 65 years, and slightly more than half were men. During an average follow-up of more than 4 years, the combined rate of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke was 15%.

The researchers used data from the 12-lead ECG recordings of these patients, as analyzed by the Cornell product equation and by Sokolow-Lyon voltage to calculate left ventricular size. They considered any patient with a Cornell product greater than 2440 mm x msec to have residual left ventricular hypertrophy. This identified 211 patients (46%) with persistent hypertrophy despite their low achieved systolic blood pressure, and 252 patients without hypertrophy.

Patients with persistent hypertrophy were significantly older (66 years), compared with those without hypertrophy (64 years), and were significantly more likely to be women (53%), compared with the 40% rate of women in the group without hypertrophy. At baseline, the two subgroups had similar average blood pressures, and on treatment the average decline in systolic and diastolic pressures were similar in the two subgroups.

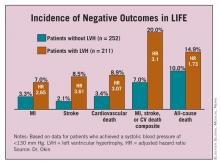

During the average 4.4 years of follow-up, patients with residual hypertrophy had significantly higher rates of MI, strokes, cardiovascular death, and all-cause mortality, as well as a significantly higher rate of the combined end point of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death, compared with the patients without hypertrophy. (See box.) These significant differences remained after multivariate adjustment for treatment allocation within the study, baseline Framingham risks score, and diastolic blood pressure on treatment.

Dr. Okin said that he receives a financial benefit from GE Medical Systems. The LIFE trial was sponsored by Merck, which markets losartan (Cozaar).