The prospects for a practical blood test that quickly detects the presence of prions in blood, organs, and tissues became more encouraging with the results of two studies published earlier this year.

But until such screening and diagnostic tests become available, the greatest concern for U.S. officials is the deferment of blood and tissue donors who have spent substantial time in countries in which variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) is most prevalent, according to speakers at a meeting of the Food and Drug Administration’s Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies Advisory Committee in August.

One test from researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases uses an antibody-based technique to isolate abnormal prion proteins and detect them at levels 10,000 times more sensitive than in previous tests for detecting vCJD. Another test from researchers at University College London Institute of Neurology and the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London was able to detect vCJD prions in the presence of the normal prion protein with a sensitivity of 71% and specificity of 100%.

The safety of the blood supply is a concern, especially in places like the United Kingdom, because of five documented cases of transmission of vCJD via blood transfusions from donors with subclinical vCJD, NIAID study investigator Byron Caughey, Ph.D., said in an interview.

"The ability of [this assay] to detect prions in plasma samples raises the possibility that this assay could be used to improve prion disease diagnosis in humans and animals and to screen the blood supply for prion contamination," wrote Dr. Caughey and his coauthors at NIAID’s Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Mont. (mBio 2011 [doi:10.1128/mBio.00078-11]). Besides its sensitivity for detecting prions in human plasma spiked with brain tissue from patients with vCJD, the assay, called eQuIC, also accurately distinguished between hamsters infected with scrapie – including some that were in early preclinical phases of infection – and uninfected hamsters.

However, they pointed out that the test has not been studied in plasma or CSF from vCJD patients and that "further studies will be required to assess the diagnostic utility of eQuIC based on the detection of vCJD seeding activity that is endogenous to these and other specimens."

In addition to helping prevent infections through the screening of blood, blood products, and transplanted tissues, if the sensitivity is dramatically improved, the test might be used to catch the disease as early as possible, before irreversible brain damage occurs; at which point treatments, as they become available, could be used. Such a test might also be used to test medical instruments such as electrodes to prevent iatrogenic transmission, as well as to detect low levels of contamination in the food supply, such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle and scrapie in sheep, Dr. Caughey said.

The test developed by English researchers was positive in 15 of 21 blood samples from patients with clinical vCJD and was negative in blood from 169 patients without vCJD. The authors said that the use of the test in the differential diagnosis of suspected vCJD would be studied further in large studies (Lancet 2011;377:487-93).

The Implications of a vCJD Blood Test

Dr. Brian Appleby, a neuropsychiatrist at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, speculated that a blood test could have "huge implications" for screening the blood supply, largely in the United Kingdom, and for use in checking deer and elk for chronic wasting disease, the main acquired prion disease seen in the United States.

A better test could also help to expedite the diagnosis of vCJD in people, who often get diagnosed very late in the course of the disease – if at all – and usually survive for less than a month after diagnosis, he said in an interview. Currently, the only forms of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease seen in the United States are the sporadic and familial types.

Of all the prion diseases, a better diagnostic test is needed for sporadic CJD, which accounts for about 85% of all human prion diseases, but there is no evidence that sporadic CJD is in the blood, Dr. Appleby said. vCJD, however, is present not only in the blood but also in lymphoreticular tissues such as the tonsils.

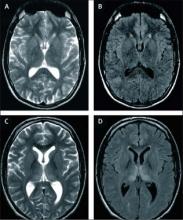

He added that sporadic CJD cases are being identified much earlier now with brain MRI, which has increasingly been used and has become very useful in making and expediting the diagnosis. Unique to vCJD is the "hockey stick" sign on brain MRI, which is a symmetrical hyperintensity in the pulvinar (posterior) nucleiof the thalamus.