In 2001, a bioattack of weaponized anthrax galvanized America’s public health care force to create a new model of emergency health response.

In ensuing years, those newly acquired skills were honed into robust emergency plans that have safeguarded millions during pandemic influenza, SARS, and even natural disasters.

But in 2011, those most intimately involved with that public health evolution fear that human complacency and political myopia might dull that invaluable edge.

A new report by the Trust for American’s Health and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation reflects on lessons learned from the anthrax incident. The report is replete with the personal stories of those who grappled with the unthinkable – a biological bombshell with the potential to kill indiscriminately and completely overwhelm an unprepared health care system.

Ironically, today’s greatly improved emergency preparedness could be a victim of its own success. As newly strengthened systems successfully shepherd the country through current public health issues, some observers warn, citizens and politicians tend to forget the struggles of the past – and to forget the importance of continued research, process improvement, and financial support.

"The biggest threat to bioterrorism preparedness today is complacency," Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), wrote in the paper. "If a health threat does not happen ... we tend to make it a lower priority. The worst thing we can do is to make something a priority after it happens. After it happens is too late; you are playing catch-up."

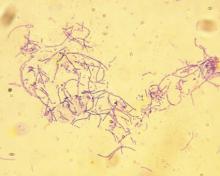

On Oct. 2, 2001, as the country was still reeling from the Sept. 11 attacks, a Florida man was diagnosed with inhalation anthrax. The case was supposedly isolated, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services determined, with the infection contracted during a camping trip.

But a few days later, officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found anthrax spores on the patient’s computer keyboard at work. At that point, it was obvious that the infection had come from an intentional anthrax release, CDC officials said in the report.

About 2 weeks later, Sen. Tom Daschle’s (D-S.D.) office received an anthrax-laced letter. By the middle of November, 22 anthrax cases had been diagnosed; five people died from the disease.

From a public health perspective, the anthrax incident was a classic case of on-the-job training, Dr. Fauci said in the report. Although federal public health officials had discussed the prospect of bioterrorism, it was still something of an abstract concept in 2001.

"The attacks were really a wake-up call," he wrote. "We did not have a clear public health response system in place for handling unexpected public health emergencies."

With the anthrax releases coming on the heels of 9/11, the country experienced "gripping fear" over what might come next. There was no time for hand-wringing, however, he said.

"I would describe the overall response as a ‘leaping into action’ on the part of scientists and public health officials," Dr. Fauci explained. "We quickly brought together leading scientific experts and developed two important paths forward" – the NIAID’s Strategic Plan for Plan for Biodefense Research and Biodefense Research Agenda. Those initiatives were developed within 5 months after the anthrax attacks, he added, and became the starting points for later updates and progress reports.

After being thrust into the age of bioterrorism, federal and local health officials saw an urgent need to beef up emergency response plans. NIAID led the way, Dr. Fauci said. "We understood that anthrax would not be the end of the story – that preparedness and development of biomedical countermeasures should not stop with anthrax."

Ultimately, he said, attacks intended to paralyze a country with fear ended up strengthening public health networks all over the United States.

"The response to the anthrax attacks morphed into a much broader effort that encompassed not only preparedness for anthrax and other potential deliberate biothreats, but also for naturally emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases that threaten both public health and national security," Dr. Fauci said. "Through the anthrax response, we built both a physical and an intellectual infrastructure that can be used to respond to a broad range of emerging threats."

Initially, the report’s authors said, the federal government stepped forward with cash and patriotism-fueled political will. Improvements included preparedness planning and coordination; support for public health labs and vaccine manufacturing; heightened surveillance and communication; increased public health staff; and expanding surge capacity at health care facilities. The Strategic National Stockpile of medications and emergency supplies also got a post-2001 boost.