Cognitively stimulating activity, particularly in early and midlife, is associated with lower brain deposition of the major protein constituent of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease later in life, based on findings from a cross-sectional clinical study.

The study’s direct association between cognitive activity and beta-amyloid (A-beta) protein suggests that the lifestyles of those with greater cognitive engagement may play a role in the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), particularly because participation in cognitively stimulating activities has been linked with other lifestyle practices associated with reduced Alzheimer’s disease risk, Susan M. Landau, Ph.D., of the University of California, Berkeley, and her colleagues reported online Jan. 23 in Archives of Neurology.

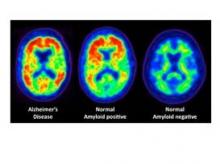

PET imaging of the binding of the radiopharmaceutical carbon 11–labeled Pittsburgh Compound B ([11C]PiB) to A-beta protein showed comparable A-beta deposition in older adults in the highest cognitive activity tertile and young controls. On the other hand, older adults in the lowest cognitive activity tertile had mean cortical [11C]PiB uptake comparable with the Alzheimer’s patients, the investigators said (Arch. Neurol. 2012 Jan. 23 [doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.2748]).

The researchers defined cognitively demanding activities in terms of activities that depended minimally on socioeconomic status, such as reading books or newspapers, writing letters or e-mails, and playing games.

The greatest association was seen between higher past cognitive activity scores (based on levels from ages 6 to 40 years, compared with those from ages 40 and older) and lower [11C]PiB uptake, but the association between cognitive activity and lower [11C]PiB uptake existed across the life span after age, sex, and years of education were taken into account, the investigators noted.

Although previous epidemiologic studies have also demonstrated a link between cognitive stimulation throughout life and a reduced risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease, these findings "suggest a novel mechanism in which increased cognitive activity may play a direct role in reducing A-beta before disease onset," they wrote.

The notion that cognitive activity influences the development of Alzheimer’s disease pathology is supported by recent findings of reduced hippocampal atrophy – another biomarker of Alzheimer’s pathology – in cognitively normal older adults with greater lifelong complex mental activity levels, they said.

"Our cognitive activity measurement is likely just one of a variety of interrelated lifestyle factors that are difficult to quantify. Cognitive activity and (marginally) years of education were associated with [11C]PiB uptake (although cognitive activity and years of education were not related to one another), suggesting that these measurements may reflect a broader underlying tendency to engage in intellectual, occupational, social, and recreational activities," Dr. Landau and her coauthors wrote.

The study’s 75 older adults included 65 healthy participants with normal cognition and a mean age of 76 years and 10 with Alzheimer’s disease who had a mean age of 75 years. A total of 11 young control participants had a mean age of 24.5 years.

The healthy older adults underwent [11C]PiB PET imaging and completed an extensive neuropsychological battery between Oct. 31, 2005, and Feb. 22, 2011. They self-reported their levels of cognitively demanding activities and physical activity.

Although physical activity was associated with cognitive activity in this study, it was not associated with [11C]PiB uptake. The addition of physical activity to the model also did not reduce the association between cognitive activity and PiB. This indicates that cognitive activity was the primary variable driving the association because physical activity was measured as a current function and cognitive activity was assessed as a lifelong engagement. Dr. Landau and her associates then proposed that the association between [11C]PiB and cognitive (but not physical) activity "may thus reflect a time-sensitive neural process in which early- and midlife practices have a greater influence on AD pathology than later-life practices."

Courtesy Susan Landau & William Jagust

Courtesy Susan Landau & William Jagust

PET scans reveal amyloid plaques, which appear as warm colors such as red and orange. The left scan is from a patient with Alzheimer's disease, and the right is from a person with no detectable amyloid deposits in the brain. The middle scan is of a person with no symptoms of cognitive problems, but who has evident levels of amyloid plaque in the brain.

It is plausible, they said, that people who participate in a variety of cognitively stimulating activities throughout life may develop more efficient neural processing that results in less A-beta deposition – an idea supported by findings in transgenic A-beta–expressing mice.

"It is unlikely that our results reflect a single unitary cause of AD, which is a complex disease with many potential pathogenetic processes. ... However, the present findings extend previous findings that link cognitive stimulation and AD risk (an indirect downstream effect of A-beta) by providing evidence that is consistent with a model in which cognitive stimulation is linked directly to the AD-related pathology itself," they concluded.