New guidelines on dyslipidemia and the prevention of atherogenesis give official sanction to something endocrinologists have been doing for years: lowering LDL targets to below 70 mg/dL for all very high-risk patients.

They also favor validating the effectiveness of LDL-lowering treatments by looking to apolipoprotein B, a measurement not yet widely used in clinical practice.

Fibrates, niacin, HDL level targets, the use of inflammatory biomarkers, and the frequency of lipid testing are other issues dealt with in the guidelines (Endocr. Pract. Vol. 18 (Suppl 1), March/April 2012, 1-78), which were published this month by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

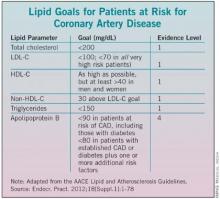

AACE’s LDL target represents a departure from the National Cholesterol Education Program’s 2004 guidelines (ATP III), which advise physicians to aim for an LDL level of less than 100 mg/dL for patients with established coronary artery disease or a 10-year risk for a cardiac event of 20% or higher based on Framingham criteria, and to consider an "optional" target of 70 mg/dL for the same patient group. (See chart.) American Heart Association guidelines, similarly, call 70 mg/dL a "reasonable" goal for very high-risk patients.

Dr. Paul S. Jellinger, lead author of the guidelines, said that aiming for an LDL below 70 mg/dL for all patients with CAD, or those with diabetes plus at least one additional risk factor, reflects both a mounting scientific consensus and current practice. For patients at high risk – including people with diabetes and those with two or more risk factors and a 10-year Framingham risk of coronary heart disease – the AACE recommends an LDL target of less than 100 mg/dl.

Though the Food and Drug Administration recently changed statin labeling to reflect a slight hyperglycemia risk associated with their use, the new AACE guideline reinforces that patients with diabetes should be treated "aggressively."

The guideline also recommends that clinicians check the apolipoprotein B levels of patients on LDL-lowering treatments. ApoB is a biomarker that indicates LDL particle number and, indirectly, particle size. "Measuring apoB is the easiest, cheapest, and most consistent way to tell us that we’ve reduced the total number of LDL particles. It is more difficult to lower apoB than to lower LDL," said Dr. Jellinger of the Center for Diabetes and Endocrine Care in Hollywood, Fla., and professor of clinical medicine at the University of Miami.

While non-HDL is also a key measurement, and should be included in all reports, Dr. Jellinger said, "we look at non-HDL as a very good way to start and apoB as a very good final measurement to ascertain that you have reached your pharmacotherapy goal."

The AACE guidelines advise physicians to look at apoB even when LDL levels appear to be well controlled and at goal and consider apoB as a secondary therapeutic target. Recommended apo B levels for patients at risk of CAD, including those with diabetes, are less than 90 mg/dL, and less than 80 mg/dL for patients with established CAD or diabetes and one or more additional risk factors. The guidelines note the evidence here is not as strong as for the other recommendations.

Measurements of homocysteine, uric acid, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 are not routinely recommended by the AACE for use in stratifying risk due to the uncertain evidence of benefit achieved by lowering these factors.

But the AACE encourages looking at the inflammatory markers highly sensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and in some patients lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2), when risk is uncertain and additional information is needed to decide how aggressively to treat.

The guidelines note that while hsCRP can be useful in stratifying patients with intermediate risk, this marker can be elevated by systemic inflammation and obesity. Lp-PLA2, an enzyme found in arterial plaque, is more specific for vascular sources of inflammation. "With both hsCRP and Lp-PLA2 elevated, it may be appropriate to be more aggressive with treatment in a patient otherwise considered at intermediate risk," Dr. Jellinger said.

Also helpful in cases requiring precise risk stratification are two noninvasive measures of atherosclerosis: carotid intima media thickness and coronary artery calcification (CAC). But since there is no definite evidence that CAC, while strongly correlated with coronary atherosclerosis, independently predicts coronary events, the guidance warns that these are not helpful when performed routinely as a screening measure, which Dr. Jellinger said they often are. Rather, "they should only be used in certain situations as adjuncts to standard CVD risk factors to refine the patients’ risk when considering more aggressive therapy," he said.

The new guidelines recommend raising HDL-C levels as much as possible for patients at risk of CAD, but minimally to greater than 40 mg/dL in both men and women.