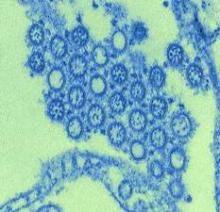

The vaccine used to counter 2009’s pandemic influenza A(H1N1) strain may have increased slightly the risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome in vaccinated older adults, according to a Canadian study. Results were published in the July 11 issue of JAMA.

The study’s investigators stressed that the benefits of immunization likely outweigh the elevated risk.

Exposure to the ASO3 adjuvant influenza A(H1N1) vaccine was associated with a small but significant increase in the risk of developing Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) within 8 weeks, with an excess of approximately two cases of the disorder per 1 million doses of vaccine, said Philippe De Wals, Ph.D., of the department of social and preventive medicine, Laval University, Quebec City, and his associates (JAMA 2012;308:175-81).

The province of Quebec launched a mass immunization campaign in the fall of 2009 to control a pandemic of the H1N1 flu. The chief medical officer of health ordered that a population-based epidemiologic study of GBS be conducted at the same time. GBS had recently been added to the list of reportable diseases there.

The immunization program targeted all 7.8 million residents of Quebec aged 6 months and older, and the vaccine was administered by the public health service only. Almost all recipients (96%) were given the inactivated monovalent ASO3 influenza A(H1N1) vaccine (Arepanrix, GlaxoSmithKline).

In addition to the mandatory reporting of GBS cases, all neurologists in the province were contacted twice a month from October of that year until the following April and asked to report both suspected and confirmed cases of GBS they had treated. Dr. De Wals and his colleagues reviewed the records of these cases, as well as the records of all GBS cases treated at all the province’s acute care hospitals during the study period, from October through March.

In all, 83 cases of GBS were included in the analysis, representing a rate of 2.3 cases per 100,000 people. That is higher than the rates of 1.1-1.8 per 100,000 that have been reported in other studies, the researchers noted.

There was a conspicuous cluster of 56 cases of GBS (67% of the total number of cases) during the 12-week period just after the immunization campaign began. In contrast, no cluster of GBS cases was seen among unvaccinated people during that period.

Two statistical methods were used to assess the risk associated with the vaccine, and both found an elevated risk during the 4 weeks following vaccination.

However, the excess risk was seen only in patients aged 50 years or older.

"The number of cases attributable to vaccination was approximately 2 per 1 million doses," Dr. De Wals and his associates said.

Similar studies in other areas of the world have produced inconsistent results.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Emerging Infections Program found a significant association between the nonadjuvant 2009 influenza A(H1N1) vaccine and GBS, with attributable risks of 1.5 and 2.8 per million doses, depending on the definition of the reference period. Those findings are very similar to the results in Quebec.

However, in the United Kingdom, no significant association was found between the H1N1 vaccines administered there and GBS. And another study in five European countries lacked the power to detect an association of a few cases per million doses, the researchers said.

The Quebec study was funded by Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Quebec and the Public Health Agency of Canada–Canadian Institutes for Health Research influenza research network. Dr. De Wals reported ties to vaccine manufacturers, including GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi-Pasteur, Merck, and Pfizer.