COVINGTON, KY. – Early electroencephalogram monitoring is playing an increasingly critical role in the recognition and management of status epilepticus, the most common neurologic emergency of childhood.

EEG is important for a definitive diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (SE), particularly in children who have been in a convulsive state and in those with encephalopathy of unknown etiology or a seizure history, Dr. Rajit K. Basu of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center said at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

This view is formed in part by a recent study at his institution, in which video EEG monitoring revealed that more than one-third of children admitted for encephalopathy (35%) were in nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Almost all had convulsive seizures prior to presenting (92%) and more than half were being cared for on the floor (Pediatrics 2012;129:e748-55).

Similarly, an earlier study reported that up to 22% of children who had prolonged EEG monitoring after convulsive SE were found to be in nonconvulsive SE (Neurology 2010;74:636-42).

"These are the kids that I think really fall through the cracks for us – the ones that got a bunch of meds in the ER and are admitted to the floor for observation because they’re ‘sleepy’ or need to ‘wake up,’ " Dr. Basu said. "But you don’t know actually that they’ve recovered, and every minute that you let them go – every minute that you don’t know they’re in nonconvulsive status – is a problem."

He acknowledged that not every institution has the capacity for emergency EEG monitoring but said the idea is for clinicians to think about an EEG at 7 or 8 a.m. rather than 2 p.m.

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defined status epilepticus in 1993 as more than 30 minutes of continuous epileptic activity without complete recovery of consciousness, although more recent definitions have shortened the duration to 20, 15, or even 5 minutes of continuous seizure activity.

Essential to the management of SE is an understanding of the inciting disease and that seizures are neurotoxic, said Dr. Basu, lead for the hospital working group on management of refractory SE.

"Seizures are not a benign thing, even if you stop them," he said. "They’re a pre-status state. Your brain is on fire and that fire needs to be put out."

Multiple diagnostic algorithms for SE exist, including one by the ILAE that is expected to be revised soon, but most are center specific or user specific. The common thread, however, is that time matters, both for treatment response and outcomes.

"If you don’t act quickly, the outcome on the backside is severe," Dr. Basu said. "Even if they don’t die, which some kids unfortunately do, there is an increased incidence of epilepsy syndrome and poor neurologic recovery."

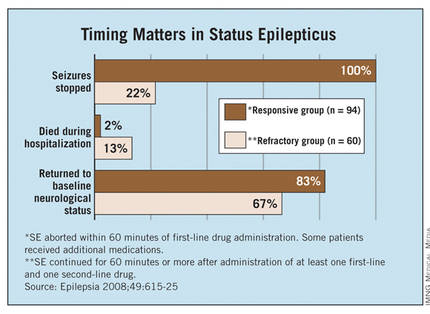

Indeed, the Mayo Clinic reported (Epilepsia 2008;49:615-25) that seizures stopped in 100% of children with SE receiving an additional second-line therapy within less than 60 minutes of the first drug, compared with only 22% of those receiving additional second-line therapy later in the clinical course. (Patients were allowed two second-line therapies before third-line treatment.)

Children in that study’s refractory SE group were significantly less likely than those treated more aggressively to return to baseline neurological status and more likely to die during hospitalization (see graph), and they had a twofold higher risk of developing a new neurological deficit or epilepsy at 4-year follow-up. (Researchers defined the refractory group as "clinical or electrographic seizures lasting longer than 60 minutes despite treatment with at least one first-line AED and one second-line AED.")

"The point is that if you follow some kind of time algorithm and deliver meds early and aggressively, you can get ahead of this and may stop status from developing," Dr. Basu said.

A continuing challenge is predicting which child presenting with SE will progress to refractory SE and likely end up in the ICU on burst suppression. To this end, Cincinnati Children’s recently launched the PARSE (Pediatric Acute Refractory Status Epilepticus) Initiative to derive a predictive model that may actually trigger a change in the "tempo" of SE management, he said.

Until predictive modeling becomes a reality, in-hospital and at-home seizure plans are being created. The London-Innsbruck Colloquium on Acute Seizures and Status Epilepticus has penned several SE protocols, with a recent review (Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011;24:165-70) detailing treatment advances since the first colloquium was held in 2007.

Hospitals are also developing at-home seizure plans that may be tailored to individual at-risk patients, featuring a red, yellow, and green light system similar to that used in at-home asthma action plans. Parents may understand the idea of giving rectal diazepam (Valium, Valrelease) at home, but such remote plans can help address questions such as when a second therapy should be delivered, the correct dosing of benzodiazepines, or when to come to the hospital, Dr. Basu said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.