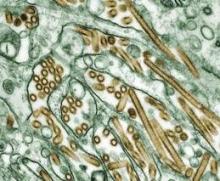

The 40 researchers who pledged a voluntary moratorium in January 2012 on studies of H5N1 avian influenza and its ability to become airborne transmissible between mammals called their moratorium off a year later, on Jan. 23.

In a letter published simultaneously in the journals Science and Nature, the international panel of 40 influenza experts said "acknowledging that the aims of the voluntary moratorium have been met in some countries and are close to being met in others, we declare an end to the voluntary moratorium on avian flu transmission studies."

But the published letter (Science 2013 [doi: 10.1126/science.1235140]; Nature 2013 [doi: 10.1038/nature11858]) also stressed that the only endorsed settings for resumed H5N1 mammalian studies are countries with established rules for conducting this research, a stipulation that for the time being shuts down this work for U.S.-based investigators.

"Scientists should not restart their work in countries where, as yet, no decision has been reached on the conditions for H5N1 virus transmission research," the letter said, a category that most notably includes the United States. Countries with rules in place and where this research can restart immediately include European Union members, Canada, China, and very soon Japan, said Ron A.M. Fouchier, Ph.D., during a press conference about the moratorium lifting.

That made Dr. Fouchier the sole researcher working on airborne transmission of H5N1 flu in mammals who could announce imminent resumption of his work, something that he said would restart in his Rotterdam lab "in the next few weeks," as soon as he receives "a new order of ferrets," he said at the news conference organized by the publishers of Science and Nature.

A second researcher who has also published results on airborne-transmissible H5N1 flu in ferrets, Yoshihiro Kawaoka, Ph.D., a professor of virology at the University of Wisconsin, said work at his lab remains down until U.S. agencies finish setting conditions for H5N1 research.

"My research on H5N1 transmission is funded by the [U.S. National Institutes of Health], so I will not be able to resume until the U.S. government decides the details of its guidelines," Dr. Kawaoka said at the press conference. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services released a draft of its new H5N1 rules last October, and while they appear to be nearing completion, U.S. agencies have given no time frame for when the finalized guidelines will be in place, said Dr. Fouchier, a professor of molecular virology at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam.

Dr. Fouchier said that topping his research agenda is further assessment of the several mutations that he previously linked to ferret airborne transmission to try to identify the minimum set of mutations needed for airborne transmission. His second immediate goal is to see whether these mutations are critical for transmission of H5N1 strains isolated from a wider number of world sites, such as from Egypt and China; the strains that he has characterized so far came from Indonesia and Vietnam. A third project will be to assess the prevalence of H5N1 in the wild that carries one or more transmissibility mutations.

The central messages delivered at the press conference by Dr. Fouchier, Dr. Kawaoka, and a third signer of the letter, Richard J. Webby, Ph.D., an influenza expert at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, were that ongoing research into H5N1 transmission is critical and must now continue, the research can be done safely, and the 1-year hiatus produced by the moratorium (Nature 2012;481:443) accomplished its goals.

"The moratorium was put in place to provide time for discussion about the risks and benefits of this research. That has been achieved. We feel that the need for this moratorium is no longer in place," Dr. Webby said.

"We want to resume research because it is important for pandemic preparedness," said Dr. Kawaoka. "The benefits outweigh the risks. The greater risk is not doing this research. The risk [from air-transmissible H5N1] already exists in nature. It’s not doing this research that really puts us in danger," he said.

The research will protect public health by identifying the mutations that occur in nature that allow airborne transmission, and will allow researchers to better evaluate antiviral drugs and vaccines for H5N1, Dr. Fouchier said.

During the yearlong moratorium, Science and Nature published papers detailing the initial transmission experiments done by Dr. Fouchier’s group (Science 2012;336:1534-41; Science 2012;336:1541-7), and the independent work done in Dr. Kawaoka’s laboratory (Nature 2012;486:420-8). At the time of the moratorium a year ago, some of the controversy over this work centered on whether these papers should be freely available as part of the scientific literature, but regulatory groups subsequently signed off on allowing publication of these reports.