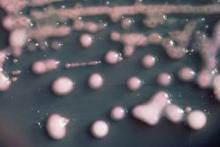

Between 2001 and 2011, the percentage of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections reported by acute-care hospitals in the United States increased nearly fourfold, from 1.2% to 4.2%. More recent data from the first 6 months of 2102 suggest that the percentage of such infections is now slightly higher, at 4.6%.

The findings, which appear in a Vital Signs report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on March 5, are significant because CRE can kill up to 50% of patients who get bloodstream infections from them.

"It’s not often that our scientists come to me to say that we have a very serious problem and we need to sound an alarm," CDC Director Tom Frieden said during a related telephone press briefing. "But that’s exactly what we’re doing today. This Vital Signs is an early warning about a health care–associated infection that’s happening in hospitals and other inpatient medical facilities. The good news is that we now have an opportunity to prevent its further spread. The sooner we act, the less likely it will get out into the community."

For one component of the report, CDC researchers analyzed data from the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) and its predecessor, the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance system (NNIS), for the number of Enterobacteriaceae isolates; the percentage reported to be tested against carbapenems; and the percentage reported as carbapenem resistant in 2001 and in 2011. For another component, the researchers evaluated NHSN data for the number and percentage of facilities reporting CRE from a catheter-associated urinary tract infection or central line-associated bloodstream infection between January and June of 2012.

Of the CRE cases reported during the first half of 2012, about 18% occurred in long-term acute care hospitals and about 4% occurred in short-stay hospitals.

Dr. Frieden characterized CRE as a "nightmare bacteria" that poses a triple threat. "First, they’re resistant to all or nearly all antibiotics – even some of our last-resort drugs," he explained. "Second, they have high mortality rates. They kill up to half of people who get serious infections with them. And third, they can spread their resistance to other bacteria such as Escherichia coli and make E. coli resistant to those antibiotics also."

The risk of CRE infection is highest among patients who are receiving complex or long-term medical care, including those in short-stay hospitals or long-term acute care hospitals, or nursing homes. It’s commonly spread by people with unclean hands but "medical devices such as ventilators or catheters [also] increase the risk of life-threatening infection because they allow new bacteria to get deeply into a patient’s body," Dr. Frieden said.

According to the report, health care facilities in Northeastern states report the most cases of CRE, with 42 states reporting having had at least one patient test positive for the infection. In addition, one type of CRE, a resistant form of Klebsiella pneumoniae, demonstrated a nearly sevenfold increase between 2001 and 2011, jumping from 1.6% to 10.4%.

"That’s a very troubling increase," Dr. Frieden said. "In some of those places, these bacteria are now a routine challenge for patients and clinicians."

The good news, he continued, "is that we still have time to stop CRE. Many facilities can act now to prevent CRE from emerging or, if it has emerged, to control it. We need health care leaders, clinicians, and health care departments to act to prevent CRE, so it doesn’t become widespread and spread to the community." He listed six practical ways that health care providers can prevent CRE in their facilities:

• Know if your particular patient has CRE and request immediate alerts from your laboratory every time it identifies any patient with the infection.

• When receiving or transporting patients, make sure to ask or find out if the patient you’re receiving has CRE.

• Protect your patients from CRE by following contact and other precautions whenever you’re treating patients with CRE "so you don’t inadvertently spread their organism to someone else."

• Whenever possible, have specific rooms, equipment, and staff to care for CRE patients. "This reduces the chance that CRE will spread from one patient to others," he said.

• Remove temporary medical devices such as catheters as soon as possible.

• Prescribe antibiotics carefully. "Unfortunately, half of the antibiotics prescribed in this country are either unnecessary or inappropriate," Dr. Frieden said. "Overuse and misuse increases drug-resistant infections. That results in longer inpatient treatment, higher costs, and poorer patient outcomes."