Dementia cost the United States economy between $159 billion and $215 billion in 2010, making it a greater financial burden than either cancer or heart disease, according to a study published April 3 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

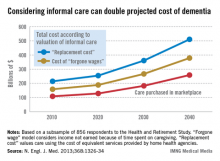

With the aging of the population, that number could climb to between $379 billion and $511 billion annually by 2040, depending on how caregiver costs are estimated. Already, the direct cost of dementia care purchased in the marketplace ($109 billion) is greater than what is spent on either heart disease ($102 billion) or cancer ($77 billion).

"We’re going to see an increasing fraction of our resources devoted to this disease," said Michael D. Hurd, Ph.D., a study author and the director of the RAND Center for the Study of Aging in Santa Monica, Calif.

The investigators relied on a subset of 856 patients who had undergone a detailed in-home clinical dementia assessment as part of the Health and Retirement Study to estimate both the prevalence and cost of dementia in the United States. Dr. Hurd and his associates extrapolated the data to estimate the probability of dementia for all study respondents older than 70 years from 2000 through 2008 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1326-34).

Estimates of the societal costs of dementia are based on the yearly per-person cost of dementia ($41,000-$56,000) and an estimated prevalence of 14.7% among Americans older than age 70.

Most of the costs associated with dementia are for home-based care or care in a long-term care facility, not for other medical services, the researchers found.

Dr. Hurd said the use of technology offers some promise for reducing those costs in the future. For example, better telemedicine might allow for lower staffing levels at long-term care facilities. And home assistance devices that could help caregivers to handle physically demanding tasks, he said.

"The role of technology could be quite important in this even if we cannot find medical advances that would delay the onset [of dementia]," he said.

The researchers presented the costs in a range to reflect the different ways to estimate the value of in-home care provided by unpaid caregivers.

Under the higher estimates, unpaid caregiver costs are calculated by determining how much it would cost to purchase comparable care from a home health agency. The lower estimates are based on the value of the caregiver’s time in the labor market. In the case of an elderly caregiver who is out of the workforce, that number would be quite low, Dr. Hurd said.

The findings also offer a message to policymakers: Invest in dementia research. "If you’re a coldhearted person who doesn’t care about the emotional side, here’s something on the economic side that you can look at and say, ‘This really is costing us a lot of money, and we ought to put some dollars into seeing what we can do about it,’ " Dr. Hurd said.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). The Health and Retirement Study is conducted by the University of Michigan and is supported by grants from the NIA and the Social Security Administration.