- Immediately upon presentation of non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), aspirin therapy (81–325 mg) should be initiated (A). If aspirin is contraindicated, clopidogrel (300-mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/d) should be administered (A).

- In patients for whom an early noninterventional approach is planned, or for patients not at high risk of bleeding for whom percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is planned, clopidogrel 75 mg (once daily) should be added to aspirin therapy as quickly as possible and continued for up to 9 months (B).

- Aggressive low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol-lowering therapy and general cardiovascular risk reduction are important in long-term management of these patients. Thus, a fibrate or niacin should be administered if the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol is <40 mg/dL (B).

- In patients with LDL cholesterol >100 mg/dL, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) and diet should be started during admission and continued after discharge (B).

In the long-term care of patients with acute coronary syndrome, recently published w that prognostic benefits improve with more aggressive antiplatelet therapy for those at high risk for recurrent events. Moreover, long-term care should include aggressive LDL cholesterol-lowering therapy and use of beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, in addition to diet modification and exercise.

STEMI and NSTEMI: The new nomenclature

Coronary artery disease, the leading cause of death in the United States,1 can manifest in many ways involving a constellation of symptoms, electrocardiogram changes, and serum markers. These acute coronary syndromes result from decreased coronary blood flow and cause chest discomfort, usually at rest, with or without characteristic radiation, or such comparable anginal equivalents as weakness, dyspnea, and diaphoresis.

STEMI. An elevated ST-segment with elevated levels of such cardiac markers as creatine kinase myocardial band or troponin I or troponin T are consistent with a diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The old term, acute myocardial infarction, was defined by the presence of pathological Q waves (Q wave MI).

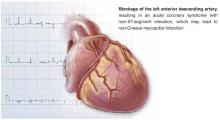

NSTEMI. Patients with elevated serum levels of creatine kinase myocardial band or troponin I or troponin T, but no ST-segment elevation, are said to have non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).

Unstable angina. Normal levels of serum cardiac markers and an absence of ST-elevation are consistent with a diagnosis of unstable angina (Figure). Of patients with STEMI, most will ultimately experience a Q-wave MI; a minority will have a non–Q-wave MI. Of patients with NSTEMI, most will sustain a non–Q-wave MI, while a minority will sustain a Q-wave MI.

Unstable angina and NSTEMI are urgent and life-threatening problems. Chest pain and related symptoms account for 5.3 million visits to US emergency departments per year2 and account for 1.4 million hospitalizations annually.3 Approximately 15% of those presenting with unstable angina and NSTEMI go on to (re)infarct or die within 30 days.4

FIGURE

Unstable angina and NSTEMI

FIGURE

Nomenclature of acute coronary syndrome

ACC/AHA Guidelines

In 2000 the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Task Force on Practice Guidelines published their evidence-based recommendations for treatment of unstable angina/NSTEMI following an exhaustive review of the literature.

New trials in acute coronary syndromes

Since 2000, knowledge of acute coronary syndromes advanced considerably with results of large pivotal randomized controlled studies, which necessitated updating the ACC/AHA guidelines just 21 months after their completion. The most notable of these studies were the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (CURE) trial,6 the Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI)-CURE7 subset analysis, and the Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering (MIRACL) trial.8

Although incorporation of antiplatelet therapy is the focus of this article, the ultimate objective of the new revised guidelines is improved clinical outcomes for patients with acute coronary syndromes by improving early risk assessment, using revascularization procedures aggressively when risk for future cardiac events is high, using short- and long-term antiplatelet and antithrombotic agents, and modifying long-term risk.

2002 revised guidelines

The studies reviewed in the 2002 revised guidelines assessed multiple therapies in the reduction of recurrent MI, stroke, and other cardiovascular events following patients’ presentation with unstable angina and NSTEMI. The studies also evaluated traditional therapies for acute coronary syndromes, such as unfractionated heparin, beta-blockers, and aspirin, as well as more recent therapies, including low-molecular-weight heparin, antiplatelet therapy (parenteral glycoprotein IIb/IIIa [GP IIb/IIIa] antagonists and ADP-receptor antagonists [thienopyridines]), lipid-lowering therapy (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, or statins), and antihypertensive agents.2

The results of these trials have lead to changes in the initial management of patients following an new ischemic event, as well as the choice of medical therapy begun in the hospital and continued following discharge. Patients are given an individualized medical regimen based on specific needs that include in-hospital findings relating to the type of recent procedure, risk factors for subsequent ischemic events and drug tolerability. Such a regimen, although beyond the scope of this discussion, can be recalled as “ABCDE,” for Anti-platelet agents/ACE inhibitors, Beta-blockers, Blood pressure control, Cholesterol (lipid)-lowering agents, Cigarette cessation, Diet modification, Diabetes control, Exercise, and Education.