CASE An 84-year-old man was admitted to our family medicine inpatient service with increasing weakness, fatigue, nausea, jaundice, and anorexia after undergoing thoracentesis for recurrent large right-sided pleural effusion twice within the past 6 weeks. The patient had no fever, chills, night sweats, chest pain, or chronic cough.

His past medical history included coronary artery disease and hyperlipidemia, and he had undergone coronary artery bypass grafting 6 years prior to this admission.

Initial vital signs included a blood pressure of 116/68 mm hg and a pulse rate of 78 beats per minute. physical examination revealed a thin but otherwise active and functional man, with the presence of scleral icterus and a 2/6 systolic murmur that was loudest at the left upper sternal border, with no pericardial knocks or rubs. There was no jugular venous distension. The patient had decreased breath sounds at the right base, but no appreciable rales, rhonchi, or wheezes, and an enlarged liver with an irregular edge approximately 7 cm below the costal margin. he had bilateral trace pitting edema of the lower extremities and an erythematous chronic venous stasis ulcer on his left lower leg that was being treated with sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim and rifampin.

Laboratory findings included a sodium level of 130 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.6 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 4.2 mg/dL; and an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6, with an otherwise normal liver profile. pleural fluid was transudative by light’s criteria, with negative pleural fluid cultures.

A chest x-ray showed right-sided airspace disease, with an associated small effusion (FIGURE 1), and an electrocardiogram (EKG) revealed a right axis deviation with flipped T waves in V3-V6 (FIGURE 2). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest performed 2 months prior to admission revealed a small right pleural effusion, moderate emphysema, and pleural plaques. A transthoracic echocardiogram performed a week earlier was significant for a normal ejection fraction without pericardial thickening, and mild dilation of the left and right atria and the right ventricle.

Our patient had recurrent transudative pleural effusions with no history of congestive heart failure, a normal thyroid-stimulating hormone, no signs of nephrotic syndrome, no risk factors for lung cancer, and a presentation that was not consistent with an acute pulmonary embolus. he had jaundice, but no risk factors for cirrhosis. A comprehensive hepatology consult suggested that the jaundice was associated with recent rifampin use, along with hepatic congestion likely due to cardiac etiology.

The patient also had a documented history of constrictive pericarditis. Although a cardiac CT scan 15 months prior to his hospital admission showed normal pericardial thickness, constrictive pericarditis remained high on our differential.

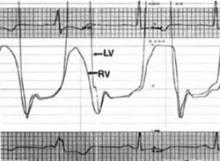

To further evaluate the patient’s cardiac function, a cardiologist performed a right-sided cardiac catheterization. in constrictive pericarditis, equalization of end-diastolic pressures occurs due to limitation of the total volume of the ventricles by a rigid pericardium. in our patient, these pressures did not equalize. his right and left ventricular pressure tracings did, however, have the classic square root sign often seen in constrictive pericarditis (FIGURE 3). This “dip and plateau” is the result of rapid filling of the ventricles during early diastole, with the inflexible pericardium causing an abrupt halt in ventricular filling.1

We considered restrictive cardiomyopathy in the differential, too, but the signs and symptoms weren’t a perfect fit there, either. equalization of left and right ventricular end-diastolic pressures in cardiac catheterization is usually not seen in restrictive cardiomyopathy, but neither is the square-root sign evident on ventricular pressure monitors.1

FIGURE 1

X-ray shows right-sided airspace disease

FIGURE 2

Right axis deviation with flipped T waves

FIGURE 3

Classic square root sign

WHAT IS THE MOST LIKELY EXPLANATION FOR HIS CONDITION?

Constrictive pericarditis

On the advice of a cardiologist who specializes in advanced cardiac imaging, our patient underwent tissue Doppler velocity echocardiography—a diagnostic test that provides evidence of a diseased myocardium (as in restrictive cardiomyopathy), as well as changes in diastolic blood flow that differentiate constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy. Our patient’s tissue Doppler velocity echocardiogram revealed a normal myocardium with an abrupt cessation of early left ventricular filling, consistent with constrictive pericarditis. Along with his clinical presentation and history, this test was conclusive enough to diagnose constrictive pericarditis.