A 54-year-old white woman with a history of a cerebrovascular accident (CVA) a year earlier sought care at the local emergency department for numbness and weakness in her right foot. She reported no other neurologic symptoms. She had mild weakness in her right leg and a mildly unsteady gait. Her neurologic examination was otherwise normal.

Initial testing included a complete blood count (CBC), renal profile, and thyroid-stimulating hormone measurement. All results were normal. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was normal. We admitted her for further evaluation of probable acute ischemic stroke.

By the following day, the patient’s leg weakness and unsteadiness had worsened. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of her head showed a prior left pontine infarct, but no new findings. She developed right arm weakness, and an MRI scan of her spine (FIGURE 1) showed multiple intradural lesions. A lumbar puncture showed elevated protein and oligoclonal bands. CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable. Two lumbar punctures for cytology and culture evaluations yielded negative results. A full-body positron-emission tomography (PET) scan showed diffuse small inguinal adenopathy bilaterally, suggestive of metastatic disease or lymphoma.

FIGURE 1

MRI of the spine

This MRI scan with contrast of the patient’s spine shows diffuse thoracic extramedullary, intradural lesions.

What is your presumptive diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Sarcoidosis

Findings from the full-body PET scan (FIGURE 2) prompted a biopsy of a right inguinal node, which showed a noncaseating granuloma—a hallmark finding of sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease of unknown cause. The exact prevalence in the general population is estimated at 10 to 20 cases per 100,000.1 A higher incidence occurs in blacks in the United States, with a 2.4% lifetime risk compared with 0.85% of whites.2 Sarcoidosis usually appears in patients ages 20 to 40 years, and although this systemic disease usually affects the lungs, 5% to 10% of patients will have nervous system involvement.3,4

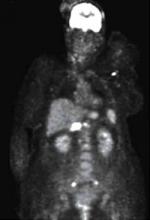

FIGURE 2

Full-body PET scan

This PET scan shows diffuse hypermetabolic adenopathy with bilateral iliac adenopathy, small hypermetabolic bilateral cervical lymph nodes, a hypermetabolic left axillary node, and a large hypermetabolic portacaval node.

What you’ll see

The most common presenting symptoms of systemic sarcoidosis are chronic cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain. Fatigue, weight loss, and myalgias are also frequently part of the initial presentation.

Patients with sarcoidosis can present with neurologic symptoms suggestive of many diseases (TABLE 1), and in the absence of systemic symptoms the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis is easily confused with CVA. Most patients with neurosarcoidosis have cranial nerve involvement (50%-75%).1 Other common presentations include seizures, meningitis, psychiatric symptoms, mass lesions, or endocrine abnormalities.

TABLE 1

Differential diagnosis of an acute neurologic event

| Infectious Encephalitis Helminthic infection HIV Lyme disease Meningitis Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy Syphilis Tuberculosis |

| Neoplastic CNS lymphoma Meningioma/glioma Metastatic disease |

| Neurologic CNS vasculitis Cranial nerve palsy Ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke Meningitis/encephalitis Multiple sclerosis Neurosarcoidosis Peripheral neuropathy Seizure |

| Psychiatric Depression Malingering Pseudoseizures Somatoform disorder |

| Rheumatologic Lupus erythematosus |

| CNS, central nervous system; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus |

Useful studies in the clinical evaluation

Consider a diagnosis of sarcoidosis involving the nervous system when an initial work-up for CVA is negative. In addition to asking about systemic symptoms, perform a complete neurologic exam and skin exam, search for lymphadenopathy, and conduct an ophthalmologic evaluation. After the initial evaluation, a neurology consult will likely be needed to guide further testing.

Choice of serum studies will vary depending on presenting symptoms, but they usually include tests for infection (CBC, cultures, Lyme titers, rapid plasma reagin, tuberculin skin test), rheumatologic disorders (antinuclear antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein), and neoplastic diseases (lactate dehydrogenase, peripheral smear).5 Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) may be useful in the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis, with positive results seen in approximately 75% of cases.3

Examination of cerebrospinal fluid often reveals an elevated total protein with oligoclonal bands, normal to low glucose, and possibly mild pleocytosis of monocytic or lymphocytic predominance.3 Spinal fluid ACE is neither sensitive nor specific for neurosarcoidosis, as it may be elevated in infectious or malignant processes.3

Imaging studies should include contrast-enhanced brain MRI, which may reveal multiple white matter lesions.6 Although the specificity of PET for neurosarcoidosis is poor—with positive results being seen also in infectious and neoplastic processes—the scan may help in identifying extraneural sites for biopsy. Histology will generally show the classic noncaseating granuloma with surrounding lymphocytes, plasma cells, and mast cells.

Treat with high-dose steroids

The mainstay of treatment, based largely on expert opinion, is high-dose steroids that are gradually tapered over weeks (TABLE 2). Other agents may be added if the condition is poorly controlled with steroids alone, or may be given if symptoms recur while tapering the steroid dose. Recurrence of sarcoidosis is common after doses of <10 to 20 mg/d. Prophylactic measures to counteract the adverse effects of long-term steroid use include weight-bearing exercise programs; administration of calcium, vitamin D, and bisphosphonates; and resorting to a stress-dose steroid regimen in times of illness.