• Suspect malignancy if a patient with a thyroid nodule also exhibits hoarseness, persistent lymphadenopathy, or dysphagia. C

• Direct your evaluation toward hyperthyroidism instead of malignancy if the level of thyroid stimulating hormone is <0.5 μIU/mL. B

• Arrange for ultrasound imaging when there is a need to assess the size, consistency, and additional features of a nodule. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

You detect a solitary thyroid nodule during a patient’s annual physical examination. He’s 50 years old, in generally good health, and has no symptoms suggestive of thyroid disease. How far would you go in your investigation?

Thyroid nodules are fairly prevalent in the United States. Although the estimated prevalence of palpable thyroid nodules is 5%,1 autopsy studies show the prevalence of all nodules to be 49% to 57%.2 Ultrasound studies of asymptomatic individuals have reported incidental detection of thyroid nodules in 35% to 67% of patients,3-5 and similar findings occur with other imaging modalities.

The main concerns with thyroid nodules are malignancy and hyperactivity. The good news is that both palpable and nonpalpable nodules carry just a 5% risk of malignancy.6 Thus, it makes sense to limit screening of nodules to individuals at high risk—eg, males, those who are younger than 30 or older than 60 years, and patients who have had radiation treatment to the head and neck, have a family history of thyroid cancer or multiple endocrine neoplasia, or have had rapid growth of a nodule and associated lymphadenopathy.6

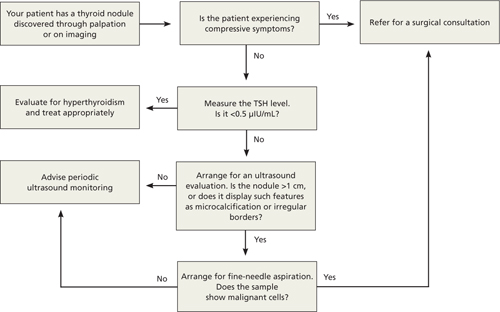

For the estimated 300,000 new nodules detected annually in the United States,7 we present a cost-effective approach to optimal diagnostic evaluation (ALGORITHM), reflecting guidelines issued by the American Thyroid Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.6,8

ALGORITHM

Recommended evaluation of a thyroid nodule6,8

How signs and symptoms can direct your investigation

Most thyroid nodules are asymptomatic and are discovered during physical evaluation or during neck imaging for unrelated reasons. When symptoms occur, they are due either to hormonal dysfunction (hyper- or hypothyroidism) or mechanical compression.

Signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism—eg, weight loss, tachycardia, irritability, sweating—suggest a “hot” nodule, which has very low malignancy potential.6

A sudden increase in nodule size accompanied by pain usually signifies acute hemorrhage into a cystic lesion. But because some cystic lesions also exhibit solid components, malignancy is a possibility.

Hoarseness, persistent lymphadenopathy, and dysphagia signal possible malignancy and should prompt aggressive evaluation.

Laboratory testing: Recommendations and cautions

Obtain a measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).6 A suppressed level (<0.5 μIU/mL) is found in about 10% of patients with a solitary nodule9; it significantly decreases the likelihood of thyroid malignancy10 and should redirect efforts toward uncovering a nonmalignant cause of hyperactivity. On the other hand, a normal or elevated TSH level does not preclude the presence of malignancy.

If the TSH level is normal, no additional information is gained by measuring thyroid hormone levels, serum thyroid autoantibodies titers (antithyroglobulin, antithyroid peroxidase), or serum thyroglobulin.

Routine measurement of serum calcitonin has been proposed as a cost-effective screen for medullary thyroid carcinoma11 in individuals at high risk, such as those with a family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia.12 However, there is no clear recommendation for its use in screening all patients with thyroid nodules.6

Imaging: Generally limit to ultrasound

Ultrasound is the best imaging modality for evaluating the size and consistency (cystic vs solid) of the thyroid nodule.13 It can also detect microcalcifications, irregular margins, lymphadenopathy, and intranodular vascularity—features suggestive of malignancy, although not confirmatory. The ultrasound finding that probably correlates most strongly with benignity is a predominantly cystic lesion.14

I123 radioactive iodine uptake and scanning is not recommended for the routine evaluation of thyroid nodules. Its role is limited to cases with suppressed TSH, as only 5% of all thyroid nodules are “hot.”15 Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET), and sestamibi scans are not cost effective in the work-up of thyroid nodules, although thyroid lesions commonly appear on these scans when they are obtained for other reasons. In particular, 18FDG-PET and sestamibi scans assess function rather than anatomy, and a finding of thyroid “incidentaloma” often leads to confusion regarding its clinical significance. Multiple reports have, however, suggested an increased incidence of cancer in 18FDG-PET-avid thyroid lesions (14%-30%)16-18; should a patient undergo this procedure and exhibit such a lesion, further investigation by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is warranted.18,19 The significance of a positive sestamibi scan for a thyroid lesion appears to be more controversial, with conflicting reports about its ability to predict thyroid malignancy.20-22