• Before considering surgery, offer patients with mild-to-moderate carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) a trial of conservative therapy such as splinting or corticosteroids. A

• Order electrodiagnostic studies (EDS) as needed, to rule out other conditions with a similar presentation, confirm an uncertain diagnosis, and gauge the severity of CTS C, or when surgery is being considered. B

• Recommend carpal tunnel release for patients who have severe CTS or have failed to respond to nonsurgical t0reatment. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE Jane K, 52, comes to see you because of discomfort in her right wrist and tingling in her hand. The symptoms began 3 months ago, but have been getting progressively worse, and have started to interfere with her sleep. Ms. K often awakens with “pins and needles” in her hand, and says that she often has the urge to “shake it out.” Her sister has carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), and Ms. K suspects that she does, too. On exam, you find that Ms. K has a positive Phalen’s and Durkan’s compression test, but normal Tinel’s test. She has normal strength and sensation in her hands. Her neck and upper extremity exam is otherwise unremarkable. You note that her hypothyroidism is well controlled, with a recent thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 1.2 mIU/L.

The patient has tried acetaminophen and ibuprofen, with little relief. She has researched CTS on the Internet and read about cold laser therapy, and wants to know whether you think it will work. What should you tell her?

Carpal tunnel syndrome is one of the most common disorders of the upper extremities and the most prevalent compression neuropathy.1 About 3% of US adults are affected, typically those between the ages of 40 and 60 years.2 Women are almost 3 times more likely than men to develop CTS.1

Other risk factors include diabetes, hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, pregnancy, obesity, family history, and trauma. A history of hand-related repetitive motions also increases the risk.3-5 Evidence does not support a definite link between keyboard or mouse use and CTS; however, occupations that require use of hand-operated vibratory tools or repeated and forceful movements of the hand/wrist (such as assembly work and food processing or packaging) are associated with CTS.6

The optimal diagnostic approach incorporates history and physical exam findings, including the results of a number of provocative maneuvers, as well as electrodiagnostic studies (EDS) in some cases.7 While surgery is the definitive treatment for CTS, numerous nonsurgical options exist, including splinting, corticosteroids, and a variety of alternative therapies, some of which (eg, chiropractic and cold laser therapy) have little evidence to support them.

Because family physicians are often the first to see patients with symptoms associated with CTS, you need to know what to look for, when to test, and whether to provide treatment or a referral. Here’s what to keep in mind.

Clinical presentation of CTS

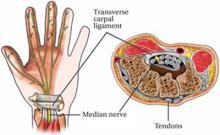

Increased pressure in the carpal tunnel compresses the median nerve, leading to numbness, tingling, or pain in the palmar aspect of the first 3 fingers and the radial half of the fourth (FIGURE). Symptoms vary widely, with pain or numbness localized to the hand or wrist in some cases and pain radiating into the forearm or shoulder in others.

Figure

Compressed median nerve leads to numbness and tingling

Early in the course of CTS, symptoms are often most bothersome at night. In a scenario like that reported by Ms. K, patients are often awakened by numbness or tingling and the desire to shake out the affected hand—a phenomenon known as the flick sign.8 Pain and numbness may occur intermittently at first, especially with repetitive wrist motion. Activities such as driving or holding a telephone often aggravate symptoms.

As CTS progresses, the intensity and duration of symptoms increase. Patients may complain of weakness in the hand and report that they often drop things. Paradoxically, patients with more severe CTS sometimes have less pain, rather than more, because of increasing sensory loss.9

Late in the course of CTS, physical exam findings typically include decreased sensation in the fingers innervated by the median nerve, sparing the thenar eminence. (A loss of sensation in the thenar eminence suggests the presence of a lesion proximal to the carpal tunnel, rather than CTS itself.10) In advanced cases, weakness of thumb abduction and opposition may occur, as well as atrophy of the thenar eminence.11

Sudden onset of severe symptoms with minimal trauma to the wrist should raise suspicion of a hematoma in the carpal tunnel—a particular risk for patients who have a clotting disorder or are being treated with newer anticoagulants such as dabigatran. Prompt surgical decompression is required to prevent permanent median nerve damage in such cases.12