Table 2 shows the outcomes for temperature and symptom score using an intention-to-treat model. The general linear model for repeated measures found average temperature significantly higher (by 0.2°C) in the immediate antibiotic use group (P = .039) and no significant difference for the symptom score (P = .29). Reanalyzing with only collected data (without intention to treat) found no significant differences from the intention-to-treat analysis. The power to detect a difference in symptom score of 30% is 80% for an alpha of 0.05, assuming that the study gives measures of variation of the symptom score that are close to the real values. There were no significant adverse effects from taking antibiotics or not. Patients’ beliefs and intentions were not affected by the interventions (Table 3).

TABLE 1

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS AND SYMPTOMS OF THE 2 GROUPS

| Immediate Prescription | Delayed Prescription | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | ||

| Number of patients | 62 | 67 |

| Male / female | 22 / 40 | 26 / 41 |

| Mean age (SD) | 27.9 years (3.1) | 23.6 years (2.7) |

| Cigarettes per day | 1.26 (0.47) | 1.17 (0.54) |

| Mean temperature (SD) | 36.9 (0.08) | 36.7 (0.08) |

| Days of illness before doctor’s visit | 4.5 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.7) |

| Total symptom score (SD) | 5.1 (0.28) | 5.4 (0.22) |

| Symptoms | ||

| Dry cough | 31 | 35 |

| Productive cough | ||

| Cough with clear sputum in morning | 8 | 5 |

| Cough with clear sputum all day | 6 | 7 |

| Cough with colored sputum in morning | 8 | 7 |

| Cough with colored sputum all day | 10 | 16 |

| Nasal symptoms | ||

| Clear rhinitis | 27 | 22 |

| Blocked or stuff nose | 21 | 26 |

| Colored runny nose | 12 | 15 |

| Night cough | 29 | 37 |

| Sneezing | 31 | 26 |

| Sore throat | 38 | 31 |

| Pain in chest on breathing in | 6 | 7 |

| Pain on coughing | 17 | 13 |

| Hoarse voice | 28 | 26 |

| Headache | 26 | 28 |

| Unwell* | 44* | 56* |

| Limitation of activities | 25 | 23 |

| Nausea | 7 | 6 |

| Vomiting | 5 | 6 |

| Diarrhea | 6 | 4 |

| * Pearson chi-square 9.134, 1 degree of freedom, P = .0025, 2 sided. | ||

| The number of patients recruited per family physician ranged from 1 to 40. | ||

| SD denotes standard deviation. | ||

TABLE 2

OUTCOMES AT BASELINE AND ON DAYS 3, 7, AND 10

| Immediate Prescription | Delayed Prescription | |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature (C)* | ||

| Baseline | 36.9 (0.1) | 36.7 (0.1) |

| Day 3 | 36.4 (0.1) | 36.2 (0.1) |

| Day 7 | 36.4 (0.1) | 36.1 (0.1) |

| Day 10 | 36.3 (0.1) | 36.1 (0.1) |

| Symptom Score (1 point for each of 15 symptoms in Table 1)* | ||

| Baseline | 5.1 (0.3) | 5.4 (0.2) |

| Day 3 | 2.9 (0.2) | 3.6 (0.3) |

| Day 7 | 1.8 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.3) |

| Day 10 | 1.4 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.2) |

| *The general linear model for repeated measures found the significantly higher temperature of 0.2°C in the immediate-use antibiotic versus that in the delayed-use group (P = .039) and no significant difference for the symptom score (P = .29). | ||

TABLE 3

SATISFACTION, ATTITUDES, AND BELIEFS

| Immediate Prescription | Delayed Prescription | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with the consultation; ie, score (1+2) / (1+2+3+4) | 58 / 62 (94%) | 64 / 67 (96%) | .71 * |

| Doctors dealt with worries | 58 / 62 (94%) | 64 / 67 (96%) | .71 * |

| Likely to see doctors for next common cold | 40 / 62 (65%) | 49 / 67 (73%) | .343 † |

| Antibiotics are effective | 47 / 62 (76%) | 51 / 67 (76%) | 1.0 † |

| Importance of seeing doctor to have time off from work or school | 19 / 62 (31%) | 13 / 54 (19%) | .16 † |

| Importance of seeing doctor to explain illness to friends and family | 6 / 62 (10%) | 7 / 60 (12%) | 1.00 † |

| * Fisher’s exact test. | |||

| † Chi-square test. | |||

| 1= very satisfied; 2 = moderately satisfied; 3 = slightly satisfied; 4 = not at all satisfied. For this table, groups responding 1 and 2 have been combined and groups responding 3 and 4 have been combined. | |||

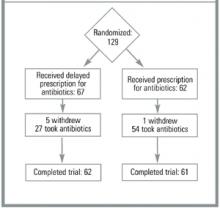

FIGURE

PROGRESS OF PATIENTS THROUGH THE TRIAL

Discussion

We believe that this is the first published randomized controlled trial of delayed prescriptions for antibiotics for the common cold. Asking patients to wait for 3 days before taking their medication reduced consumption of antibiotics from 89% to 48% (P = .0001). The 41% reduction is smaller than that found in the study by Little and colleagues11 of 1% in the take-now group and 69% in the delayed-prescription group. Patients in the UK study returned to the office in 3 days to pick up their prescription, whereas the New Zealand group received the prescription with instructions to wait 3 days before filling it. If the third day had occurred on a weekend, the patients would have had to seek assistance from an after-hours clinic, thereby incurring a direct patient charge.

Our study assessed only the effect of delayed prescriptions, whereas the study by Little and colleagues tested the combined effect of a delayed prescription and the barrier of having to return to the clinic to obtain the prescription. Furthermore, our approach may be more acceptable to a wider group of doctors and patients, although at the expense of a higher consumption rate.

The external validity (generalizability) of this study is difficult to assess. As with the study by Little and colleagues,11 the FPs had different rates of recruitment. One investigator in the current study (B.A.) kept a list of all patients who presented to him with symptoms of the common cold. Of the 44 who were potentially eligible, 4 refused to be part of the study and 10 had other medical problems (eg, heart transplant, previous lung removal) that would have made inclusion potentially hazardous. Thus, 88% of those who had a common cold and were eligible may have participated in the study.