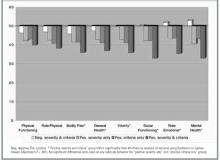

Unadjusted mean values from SF-36 subscale scores across the 4 study groups are shown in Figure 2. Although we saw no differences in the “physical functioning” and “role-physical” subscale scores among the groups, a consistent pattern emerged for the remaining 6 subscales. The “high severity and DSM positive” group had significantly lower mean scores (indicating more impairment) than each of the other 3 groups, whereas the “low severity and DSM negative” group had significantly higher scores than each of the other 3 groups. The other 2 groups’ means were in the middle and almost identical across all 8 subscales, indicating that these 2 groups were similar on each SF-36 measure of physical and mental health functioning.

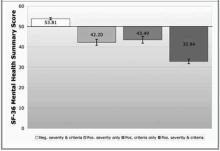

FIGURE 1

Mean deviations from standardized SF-36 subscale norms

FIGURE 2

Mean deviations from standardized SF-36 subscale norms

Mean health care charge comparisons

Briefly, adjusted mean health care charges for each group of subjects showed significant charge differences between groups for the period 3 months before the index visit. The adjusted mean health care charges for this period are shown in Figure W1.

Discussion

We believe that the central findings of this study support a severity-targeted screening strategy. The answer to our first study question—Can the addition of a symptom severity scale effectively “filter out” a group of patients who meet diagnostic criteria for “threshold” depression but have less impairment?—is “yes.” We were able to separate patients meeting criteria for depression into 2 groups, roughly one third with mild symptom severity and roughly two thirds with moderate to severe symptom severity.

The answer to our second question—Does this filtering strategy filter out patients who are in need of treatment?—appears to be “no.” The patterns of HRQOL scores and health care utilization seen for the “filtered-out” patients were indistinguishable from those of a third group of more severely symptomatic patients who did not meet depression criteria at the time of screening and who would not routinely be considered candidates for antidepressant treatment. The presence of a cohort of “middle-ground” patients has been noted in other cross-sectional primary care samples.14 Whether these patients represent persons with “major depression-in-waiting” or simply distressed and sad individuals is debatable, but there is no evidence to suggest that immediate detection and treatment lead to improved outcomes for these patients. Therefore, in routine clinical practice there would appear to be little risk in failing to identify and treat these patients unless or until their symptom severity increases.

This study does contain some important limitations. First, its cross-sectional nature does not allow us to address important questions about the middle-ground (“high severity only” and “DSM positive only”) patients, such as when they might warrant treatment, whether or when rescreening is useful, or whether “watchful waiting” is the appropriate clinical strategy for these 2 groups. Also, our decision to include as “DSM positive” those patients meeting criteria for dysthymia and MDD in remission deserves a brief explanation. Our previous work with this sample suggested that many patients meeting criteria for these 2 syndromes had high levels of distress and might be thought of as “depressed” by clinicians in routine practice. We included them to make our stratification strategy more closely representative of usual primary care practice. Repeat analyses including only MDD patients as “DSM positive” did not change our primary findings and conclusions, but they did—as expected—decrease the number of subjects in the “positive severity and criteria” group as well as increase the number of subjects in the “high severity only” group.

Despite these limitations, we believe that the results of this study offer hope to practicing physicians trying to cope with the growing depression screening mandate. Primary care physicians seeking to implement depression screening must deal with the fact that depression-screening protocols impose significant burdens on busy clinicians. In the setting of high competing demand15,16 in primary care, this additional effort—or “cognitive burden”— may render such screening impossible to accomplish in a routine clinical encounter. Several studies support this notion. Rost et al17,18 found that a screening protocol was not sustainable in primary care, in large part because primary care clinicians were unable to determine which screened patients were most in need of treatment. Dobscha et al19 found that clinicians failed to adhere to even a limited practice-based screening protocol. Williams et al20 found no difference in treatment rates or short-term outcomes when comparing brief (1-question) and comprehensive (20-question) case-finding protocols with customary clinical care.

Our results suggest that a simple refinement to a screening protocol—ie, using a brief severity measure to target the patients most appropriate for further DSM diagnostic evaluation—could help clinicians in 2 ways. First, it could decrease the burden of positive screening results by one third according to this study. Second, it could provide a more specific “prompt to act” rather than the “prompt to consider” provided by the use of current DSM criteria–based instruments. The importance of this last point should not be underestimated. Valenstein et al21 demonstrated that clinicians’ perceptions of the value of positive screen results are closely linked to their likelihood to initiate treatment. If we can enhance the value of the positive prompt, we can improve the rate of response to prompting.