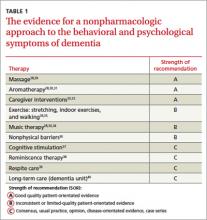

› Attempt nonpharmacologic treatment for dementia behavioral problems before moving on to medications, which are of questionable efficacy for symptoms other than aggression and psychosis. A

› Obtain informed consent from patients and/or their caregivers if you plan to use antipsychotic medications because their use increases morbidity and mortality in the elderly. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE Ms. M, 86 years old, lives with her daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughter. For several years she has been forgetful, but she has never had a formal work-up for dementia. Her daughter finally brings her to their primary care physician because she was refusing to take showers, was increasingly irritable, and had tried to hit her daughter’s husband.

In the office, however, Ms. M is calm and pleasant. The family says that most nights Ms. M gets up and wanders around the house. She denies feeling depressed or anxious, but her Folstein Mini-Mental State Exam score is 22/30, indicating moderate dementia. (For more on assessment, see “Tools for assessing patients with dementia—and their caregivers” on page 552.)

The physician offers a trial of risperidone 0.25 mg at bedtime to assist with sleep and behavior.

Was this prescription a wise decision? What other questions should this physician have asked?

Understanding the behavioral symptoms

Noncognitive symptoms of dementia, sometimes referred to as behavioral and psychological symptoms, are common, affecting almost 90% of patients with dementia,1-3 which itself can be classified as early, intermediate, and late.

In early dementia, sociability is usually not affected, but patients may repeat questions, misplace items, use poor judgment, and begin to have difficulty with more complex daily tasks like finances and driving.

In intermediate dementia, basic activities of daily living become impaired and normal social and environmental cues may not register.

In late dementia, patients become entirely dependent on others; they may lose the ability to speak, walk, and eventually, eat. Long- and short-term memory is lost.

Behavioral symptoms most often occur when the condition enters the intermediate phase, but they may occur at any time during the course of the disease.4 Behaviors may include refusal of care, yelling, aggressive behavior, agitation, restlessness, reversal of the normal sleep-wake cycle, wandering, hoarding, sexual disinhibition, culturally inappropriate behaviors, hallucinations, delusions, anxiety, depression, apathy, and psychosis.2,5

Behavioral disturbances often overwhelm families, and lack of treatment increases patient morbidity, may result in physical harm, and almost always precipitates institutionalization.2 Dementia-related behavioral disturbances also increase the risk of caregiver burnout and depression.2

These symptoms are difficult to treat with medications or nonpharmacologic therapy and strong evidence for most therapies is lacking. Physicians have historically prescribed either typical or atypical antipsychotics in an attempt to control these behaviors. In fact, medication is often still considered first-line therapy.6,7

CASE Ms. M’s daughter calls the clinic 2 weeks after the initial visit to tell the physician that her mother has been sleeping much better, but had a fall and was admitted to the hospital for a hip fracture. That’s not surprising; typical and atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of falls in the elderly.8

The risks associated with the use of antipsychotics

In 2005, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a black box warning for atypical antipsychotics because they were found to increase mortality in the elderly. The increased mortality is due to cardiac events or infection.9,10 In 2008, the FDA warning was added to typical antipsychotics, as well.11,12 Both typical and atypical antipsychotics have been found to increase the risk of falls and strokes in the elderly,8,13 and their efficacy in treating the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia has recently been questioned.13-16

Trazodone and medications approved for the specific treatment of cognitive decline, such as donepezil or memantine, are also prescribed for behavioral disturbances, but evidence to support their efficacy is limited.14,17-20 More recently, a meta-analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) suggests that they may be effective for treating agitation associated with dementia.21 However, SSRIs may also contribute to falls and to hyponatremia in the elderly.22,23

Pharmacologic Tx is not your only option

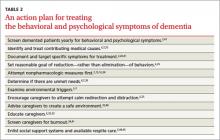

Considering the questionable safety and efficacy of pharmacologic treatment, physicians should consider nondrug therapies first, or at least concurrently with medication.2,15,16,24

But before you get started, be sure to look for and treat medical conditions that cause or contribute to behavioral disturbances, including infection, pain, and adverse effects of medication.6,7,25 Similarly, it is essential that unmet needs, such as hunger, thirst, or desire for attention or socialization, be addressed.6,7,26 Also, discuss disturbing environmental factors, including loud noises, poorly lit quarters, and strong smells, with patients and their caregivers.5-7 In complex situations, you may need to seek assistance from a geriatrician, neurologist, geropsychiatrist, or psychologist, although their availability may be limited.6