› Recommend that women consider having a single mammogram at age 40 as a baseline so that breast density can be included in the assessment of risk. minor MRSA skin lesions in children with mupirocin. C

› Advise women with low breast density and no other significant risk factors that they are at lower than average risk for breast cancer and should consider this when discussing when to begin routine screening with their physician. C

› Recommend that women with a 2-fold increased risk for breast cancer begin regular screening in their 40s. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

“Doctor, when should I start having mammograms?” That’s a question you’re apt to hear again and again from women in their early 40s. It’s also a question with no easy answer.

While deaths from breast cancer are declining, it remains the most commonly diagnosed cancer among US women. In 2012, approximately 229,060 new cases of breast cancer were detected and an estimated 39,920 women died from breast cancer1—about 10% of them in their 40s.2

Based on these numbers alone, it would seem that every woman should begin regular screening at age 40. Yet there are many other issues to consider, namely the high rate of false positives, as well as the overdiagnosis and overtreatment associated with such screening. Further complicating matters is the fact that there is no consensus as to whether screening mammography should be recommended—and if so, how often—for women ages 40 to 49 years who are at average risk.

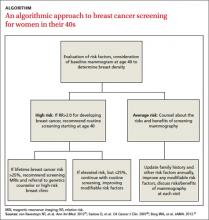

In light of this, we offer a risk-based strategy to mammography for younger women, which we’ve distilled into an ALGORITHM. But first, let’s look at the evidence and what the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and major medical groups have to say.

To screen or not to screen? A look at the evidence

A decision to perform screening mammography in premenopausal women should be made by weighing benefits vs harms. Benefits include diagnosis of breast cancer when it’s in an early stage and a reduction in death. Meta-analyses have consistently shown that routine screening mammograms for women in their 40s can reduce mortality from breast cancer by 15% to 20%.3-5 As noted by Cochrane reviewers in a meta-analysis of 7 randomized controlled studies of breast cancer screening in younger women, a 15% relative risk (RR) reduction represents an absolute risk reduction of 0.05%.5

Potential harms include the financial cost; the screening regimen itself, which includes radiation exposure, pain, inconvenience, and anxiety; the ensuing diagnostic workup in the case of false positive results; and overdiagnosis—ie, detection of lowgrade cancer that would not have otherwise become clinically evident—and subsequent overtreatment.6 Diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) was rare before the advent of screening mammography. Now, DCIS accounts for 25% of all breast cancer diagnoses, and more than 90% of cases are detected only by imaging.6 A large epidemiologic review published in 2012 suggested that the increase in breast cancer survival over the last 30 years is due to improved treatment regimens, not early detection.7

Recommendations are equivocal

Groups like the USPSTF, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Cancer Society, among others (See TABLE W1,8-17 at the end of this article), recognize that women in their 40s may benefit from screening mammography. They generally acknowledge, however, that, the evidence is not strong enough to definitely recommend routine screening mammograms due to the higher risk of false positives and the lower overall incidence of breast cancer in this age group.

The USPSTF set off a firestorm in 2009 with its initial recommendation against routine screening for women in their 40s.8 Shortly after, the group issued an update to “clarify their ... intent,” stating that the decision to start regular screening mammography before age 50 should be an individual one based on patient values as well as an assessment of benefits and risks.8

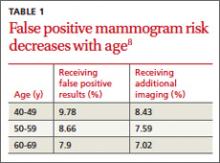

False positives decline with age

The risk of having a false positive result on a screening mammography decreases with increasing age, as the incidence of breast cancer rises (TABLE 1).8 More than 1900 women in their 40s need to undergo screening mammography in order to prevent just one death from breast cancer in 11 years of follow-up,8 with a direct cost of more than 20,000 visits for breast imaging and approximately 2000 false positive mammograms. In contrast, fewer than 400 women in their 60s would need to be screened in order to prevent one breast cancer death in 13 years of follow-up.18 A large prospective cohort study (N=169,456) found that women who started annual screening at age 40 had a 61% chance of receiving at least one false positive mammogram result over the course of 10 years; the chance of a false positive dropped to 41.6% with biennial screening.19