› Consider adding a question about fecal incontinence—a condition often unreported by patients and undetected by physicians—to your medical intake form. C

› Use bowel diaries and fecal incontinence grading systems, as needed, to better understand the extent of the problem and assess the effects of treatment. C

› Consider sacral nerve stimulation, the first-line surgical treatment for fecal incontinence, for those who fail to respond to medical therapies. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Estimates suggest that about 18 million adults in the United States suffer from fecal incontinence.1 But because the condition often goes unreported by patients and undetected by physicians, the actual prevalence is not known—and may be considerably higher.

What is known is that fecal incontinence carries a substantial socioeconomic burden. The average annual per patient cost is estimated at $4110.2 But fecal incontinence also exacts a heavy personal toll, and is one of the main reasons elderly individuals are placed in nursing homes.3

But it’s not just the elderly who are affected. A recent study of women ages 45 years and older found that nearly one in 5 had an episode of fecal incontinence at least once a year, and for nearly half, the frequency was once a month or more.4 Less than 3 in 10 reported their symptoms to a clinician, but those who did were most likely to have confided in their primary care physician.5

Fortunately, recent developments—most notably, sacral nerve stimulation, a minimally invasive surgical technique with a high success rate—have changed the outlook for patients with fecal incontinence. Here’s what you need to know to help patients who suffer from this embarrassing condition achieve optimal outcomes.

Risk factors and key causes

Maintaining fecal continence involves a complex series of events, both voluntary and involuntary. Problems at various levels—stool consistency, anatomic and neurologic abnormalities, and psychological problems among them—can disrupt the process.

Those at high risk for fecal incontinence, in addition to the elderly, include patients who are mentally ill and institutionalized, individuals with neurologic disorders, patients who have had anorectal surgery, and women who have had vaginal deliveries.6-8 Obstetric and operative injuries account for most cases of fecal incontinence.9-10

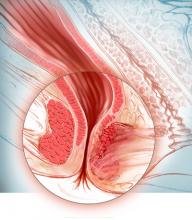

Sphincter defects including attenuation and scarring (shown here), are commonly caused by obstetric and operative injuries.

Risks of vaginal delivery

As many as 25% of women report some degree of fecal incontinence—although often confined to loss of control of flatus—3 months after giving birth.11 Stool incontinence is more frequent among women who sustained third- or fourth-degree perineal tears. Obstetrical risk factors include first vaginal birth, median episiotomy, forceps delivery, vacuum-assisted delivery, and a prolonged second stage of labor.

Asymptomatic sphincter defects. Studies in which women underwent endosonographic examination of the sphincter complex both before and after vaginal delivery have found sphincter defects in anywhere from 7% to 41% of new mothers.12-14 It is important to note, however, that as many as 70% of those with defects detected by sonogram were asymptomatic.15 (Despite the risk of sphincter injury during vaginal delivery and evidence suggesting that the risk of fecal incontinence increases with additional deliveries after a previous perineal tear, prophylactic cesarean section is not recommended.)

Fistula surgery and postop incontinence

Fistula surgery is the primary cause of postoperative incontinence, typically resulting from inadvertent injury to either the internal or external sphincter muscle.16 Other relatively common causes of fecal incontinence are rectal prolapse, trauma, irradiation, neurologic and demyelinating disorders such as multiple sclerosis, neoplasms, stroke, infection (eg, of a perineal wound), and diabetes.17 As diagnostic modalities have improved, much of what was previously termed idiopathic incontinence has been found to have identifiable underlying pathology, such as pudendal and inferior hypogastric neuropathies.18-20

Identifying fecal incontinence starts with a single question

As already noted, most patients with symptoms of bowel leakage do not voluntarily mention it to their physician. Many are likely to acknowledge the problem, however, if they’re specifically asked. While little has been written about how best to screen for fecal incontinence, simply adding it to the checklist on your medical intake form may be a good starting point.

Follow up with a targeted history and physical

When a patient checks fecal incontinence on a form or broaches the subject, it is important to question him or her about medical conditions that may be related. These include urinary incontinence, prolapsing tissue, diabetes, and a history of radiation, as well as childbirth. A medication history is also needed, as certain drugs—including some antacids and laxatives—have been implicated in fecal incontinence.21