ATLANTA – Pre–bariatric surgery psychoeducation and compliance contracts are two ways to help lower the risk of patient alcohol abuse after surgery.

"Surgery itself changes a patient’s susceptibility to alcohol," said Leslie Heinberg, Ph.D., director of behavioral services for the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Cleveland Clinic. "There’s going to be increased sensitivity to alcohol and decreased tolerance," Dr. Heinberg said at Obesity Week, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Programs that screen and triage bariatric surgery candidates, as well as inform them of how alcohol will affect them post surgery, can help manage their risk, according to Dr. Heinberg.

"I tell patients: ‘You’re going to get drunk very easily, very quickly, and it’s going to last a very long time.’ "

Dr. Heinberg cited a case cross-over trial that showed how at 6 months post gastric bypass surgery, patients had higher postoperative peak blood alcohol content levels after drinking one 5-ounce glass of red wine, and took longer to recover than they did before surgery.

"Patients that have one glass of red wine before surgery, they’re about at .02 [blood alcohol content], and they’re legally fine," she said. "Six months after surgery, they’re legally drunk." (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2011;212:209-14).

The physical experience of drinking alcohol changes post surgery, too. "Postop, people are more likely to report that they feel dizzy and lightheaded and have double vision," said Dr. Heinberg, also professor of medicine in the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University.

‘Addiction transfer’

Reasons for the increased susceptibility in this patient population include the change in ratio between body weight and alcohol concentration, as well as the physiologic change inherent to gastric bypass where a pouch is placed in the jejunum. "There is a bolus of alcohol that hits and hits very quickly," said Dr. Heinberg.

Another reason is that in weight-loss surgery, one of the body’s primary sources of antialcohol dehydrogenase, the stomach, has been reduced in volume, she said.

Dr. Heinberg also said new data suggest "addiction transfer," thought to be the result of the body’s shared neural pathways for compulsive eating and substance abuse, might lead to either relapse in patients with histories of alcohol abuse or new-onset alcoholism in those who may not have abused alcohol, but who were compulsive eaters (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011;68:808-16).

Risk predictors

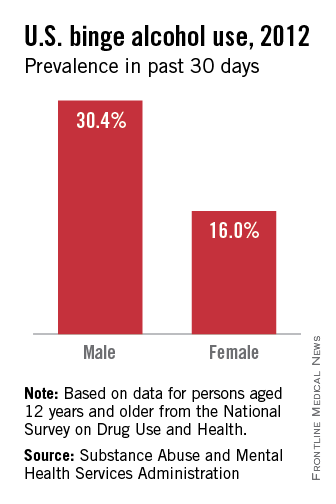

Dr. Heinberg cited a longitudinal study showing that predictors of risk included being male; presurgery use of tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drugs; having weak social support networks; and having gastric bypass surgery rather than other surgical weight loss procedures (JAMA 2012;307:2516-25).

The "good news," said Dr. Heinberg, is that contrary to her own hypothesis, a study of 400 patients with a history of substance abuse, controlled for presurgical body mass index, surgery type, gender, and race showed that people with a history of substance abuse had lost more weight 2 years after surgery (Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2012 8:357-63).

"I think people who achieve abstinence have figured out how to completely change their lifestyle," said Dr. Heinberg. "Maybe those skills that helped them quit drinking are helping them post surgery."

Improved compliance

In an online questionnaire, 84% of 318 bariatric surgery patients surveyed admitted they continued to drink after their surgery, said Dr. Heinberg. "I think it’s important to screen each and every patient for all kinds of alcohol problems."

To help ensure compliance, she suggested clinics use free screening tools and guidelines available from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. She described various levels of psychoeducation in use at her clinic, depending upon how severe the risk per the screening.

Participants deemed by her clinic to be at greater risk are given substance risk reduction education, which includes pre- and posttests. This helps avoid patients’ claims that they were unaware of the risks of alcohol after the surgery, said Dr. Heinberg. "We just pull out the test and say, ‘You got a 100%."

In some cases, she suggested that asking a patient who is a compliance risk concern to sign a contract agreeing not to drink after the surgery might help "get around risk management."

Dr. Heinberg concluded that this is a "vulnerable" patient population that may not be aware of the risks posed by alcohol post surgery. "Most programs need to think about putting this in their informed consent and providing more psychoeducation prior to surgery, sometimes even behavioral contracts," she said.