For wounds that result from a surgical procedure, employ appropriate site preparation and sterile technique. Iodophors provide broad-spectrum coverage, are not associated with microbial resistance, and provide a bacteriostatic effect as long as they remain on the skin. They require at least 2 minutes of contact to release free iodine, which exerts antibacterial activity.

Chlorhexidine gluconate offers broad-spectrum coverage against bacteria, yeast, and molds. It appears to provide greater reduction in skin microflora than povidone-iodine, and remains active for hours after application.7 Use it with caution around the eyes because of the risk for conjunctival irritation, keratitis, or corneal ulceration.8 Make sure to apply the prep solution to an area larger than the area exposed by the fenestrated drape because the drape may move around during the procedure, inadvertently contaminating the surgical field.

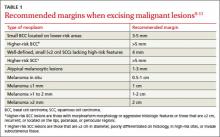

When excising a neoplasm, consider the margin

When performing a surgical procedure such as removing a cutaneous neoplasm, don’t resect excessive tissue, but do excise adequate margins. (For adequate margins of various cutaneous neoplasms, see TABLE 1.9-11) Mark the outlines of the visible tumor and the excision margin and show them to the patient, because some patients mistakenly assume that only the visible tumor will be removed.

Keep in mind when treating basal cell carcinomas (BCC) or squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) that the presence of high-risk characteristics may require larger surgical margins. The cure rates are lower for higher-risk BCCs, such as lesions that have morpheaform morphology or aggressive histologic features, or those that are ≥2 cm, recurrent, or located on the lips or paranasal or periocular regions.10-12

Cure rates for these higher-risk BCCs can be improved substantially by using intraoperative margin evaluation (frozen sections) or Mohs micrographic surgery. (For more on Mohs surgery, see “When to consider Mohs surgery,” J Fam Pract. 2013;62:558.)

Primary SCCs that are ≥2 cm in diameter, poorly differentiated on histology, in high-risk sites, or invading subcutaneous tissues require larger margins.13 The approach to a suspicious pigmented cutaneous neoplasm consists of an initial biopsy or excision with 1 to 2 mm margins and pathologic evaluation.14

Because hematoma formation inhibits wound healing, pay special attention to hemostasis when excising a neoplasm. Use pressure for minor bleeding. Use mosquito forceps to clamp a bleeder followed by ligation with an absorbable suture for larger bleeders. Other techniques for hemostasis include electrical or chemical cauterization and hemostatic solutions.

Positioning of edges is key to minimize scarring

When suturing a wound—whether it is from an injury or a procedure—take care to evert the skin edges; the underlying dermis from both edges should touch. This is to compensate for future contracture of the wound and thus, to produce a flat scar. It is difficult to evert the edges when they are too far apart or under tension, and excess skin tends to invert the skin edges, which is undesirable. If the pressure generated by the suture is greater than the closing pressure of the skin capillaries, the result will be local necrosis.

Before placing the suture, gently pinch the skin edges together. If the skin edges require pressure to approximate, consider undermining the skin edges, that is, cutting the fibrous septae that connect the skin to the underlying fascia so you can more easily pull the wound edges together. Undermining can be performed with a scalpel blade, scissors, or by bluntly using a hemostat. Use skin hooks or forceps to lift the wound edge. The safest level of undermining is in the fat, just below the dermal-fat junction. It usually takes 2 to 3 cm of undermining to free up 1 cm of tissue. Periodically check to see how much tissue has been released and undermine the minimum amount necessary.

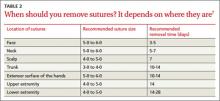

Use the recommended size suture for the area of the body and remove sutures at recommended times (TABLE 2).7 In general, use the thinnest suture for the least amount of time possible. When giving the patient wound care instructions, emphasize the importance of having the sutures removed on time. Delay may cause local irritation and increased scarring. To prevent suture marks, consider earlier removal of a single suture that causes extra tension (such as a vertical mattress suture, which is described on page 186) within a line of simple sutures. Infection or patient factors such as age, presence of vascular or chronic disease, and nutritional status may influence healing times and suture removal times, so carefully assess wound healing; it may be necessary to remove sutures earlier or later than the recommended time.