PARIS – Weight loss of more than 5% produced clinically meaningful improvements in knee osteoarthritis, even when final body mass index remained high, a large, community-based study has shown.

For those patients who lost 10% body weight in the study, knee osteoarthritis symptoms improved by about 40%, consistent with the recent IDEA (Intensive Diet and Exercise for Arthritis) trial findings.

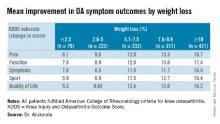

"There is a strong dose-response relationship between percentage weight loss and improvement in knee pain, function, symptoms, sport or recreation, and quality of life," Dr. Inoshi Atukorala said at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

Dr. Atukorala described the study as the first to examine the dose-response relationship between changes in body weight and knee osteoarthritis in a real-world, community setting.

The researchers evaluated 1,383 Australians who fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology criteria for knee osteoarthritis (OA) and were enrolled in the structured, remotely delivered "Healthy Weight for Life" knee and hip osteoarthritis management program. It integrates intensive weight loss as a component of tailored interventions, with the aim of achieving a 7%-10% body weight loss over 18 weeks, explained Dr. Atukorala, a consultant rheumatologist at the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

The program uses a partial very-low-calorie diet, portion management tools and devices, written healthy eating advice, and lifestyle education together with targeted telephone, e-mail, and text-message motivation and support. All participants were given the same strength, balance, and mobility exercise tools, instruction, and support.

At baseline, 81.7% of participants were obese, the average body mass index (BMI) was 34.3 kg/m2, and the mean Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) pain and function subscale scores were 56.3 and 59.5. The cohort was 71% female and had an average age of 64 years.

At 18-weeks, there was a clear and significant incremental improvement in KOOS subscales across the weight-loss categories, with the greatest improvements in those losing at least 10% body weight, Dr. Atukorala said.

The weight-loss category cutoffs were chosen based on the IDEA trial (JAMA 2013;310:1263-73), as well as the weight-loss goal in the diet groups in the ADAPT study and the weight loss typically achieved in its exercise-only cohort of older adults with knee OA (Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50;1501-10), she explained.

Using repeated measures analysis of covariance, the investigators next examined the dose-response of weight loss, compared with differences in pain and function. For this analysis, the 2.5% or less weight-loss category was set as the reference.

The dose-relationship between weight loss and improvements in pain and function persisted, even after controlling for baseline age, gender, weight, height, and KOOS, Dr. Atukorala said at the meeting, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International. The differences reached statistical significance on all KOOS subscales for the two highest weight-loss categories and on all but one subscale (KOOS sport) for those losing 5.1%-7.5% body weight.

"We are limited by the fact that the program did not assess the magnitude of exercise interventions in each weight-loss category, but it confirms the dose-response benefit of weight loss as a therapeutic intervention in knee osteoarthritis," Dr. Atukorala concluded. "And, it demonstrates the effectiveness of disseminating and implementing intensive weight-loss intervention in a community-based setting."

Dr. Atukorala reported no financial disclosures. One coauthor is the CEO and scientific director of Prima Health Solutions, and another is funded by the Australian Research Council future fellowships program.