Drug-induced thrombocytopenia (DIT) should be considered in any child who is taking or recently took a medication that may cause thrombocytopenia. Medications that can cause thrombocytopenia include heparin, quinine, vancomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, rifampin, carbamazepine, phenytoin, piperacillin, linezolid, and valproic acid.8 The measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine also can cause thrombocytopenia.8 A careful medication history may determine if the child is at risk for DIT.

To narrow the differential, obtain a CBC and peripheral smear when evaluating a patient you suspect may have ITP5 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). A CBC will determine the patient’s platelet count and a peripheral smear should be obtained to exclude other possible diagnoses.5

If there are any questions regarding the results of a peripheral smear, it may be necessary to perform a bone marrow aspiration. This, however, is not usually necessary in an otherwise typical case of ITP.9 Bone marrow aspiration may, however, be necessary to reevaluate the initial diagnosis for a child who does not respond to treatment for ITP.

Corticosteroids, IVIg are usually effective

The first step in treating a patient with ITP is to limit the risk of further injury or bleeding, by stopping nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or ending participation in contact sports2,9 (SOR: C). The next step is to determine if pharmacologic therapy is warranted.

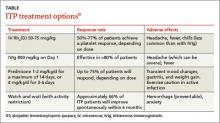

Medication, if necessary, is the mainstay of treatment for patients with ITP, particularly those experiencing significant bleeding.2 Corticosteroids, intravenous (IV) immunoglobulin (IVIg), and IV Rho(D) immune globulin (also known as anti-D) are the medications typically used to treat a child with ITP, depending on availability of the drugs, bleeding or bleeding risk, as well as convenience of dosing. For example, corticosteroids can be used orally or IV, whereas IVIg and IV Rho(D) may not be readily available in some treatment settings.

Corticosteroids have been shown to more rapidly increase platelet count compared to placebo and appear to have a dose-related effect.10,11 Oral prednisone can be dosed at 1 to 2 mg/kg/d for 14 days and then tapered over the course of one week10,11 or one may prescribe 4 mg/kg/d for 4 days.10,11 IV methylprednisolone typically is given at 30 mg/kg/d for 3 to 4 days.9

IVIg may have greater efficacy than corticosteroids in treating ITP, but it may also cause adverse effects, including nausea, headache, and fever. IVIg can be administered as a single 800 to 1000 mg/kg dose, or as a daily 400 mg/kg dose for 5 days; higher doses should be reserved for patients with severe bleeding.12

If ITP persists despite the use of corticosteroids or IVIg, IV Rho(D) Ig may be used in patients with Rho(D)-positive blood at a single dose of 25 to 50 mcg/kg, with additional doses administered on separate days as required to elevate platelet count. However, only Rho(D)-positive patients are eligible for anti-D treatment.

The response rates/times and adverse effects of common treatments for ITP are summarized in the TABLE.9 A small randomized study found that oral methylprednisolone 30 mg/kg/d for 3 days followed by 20 mg/kg/d for an additional 4 days was comparable to IVIg 0.4 g/kg/d for 5 days.11 A different study that compared oral methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg/d or 50 mg/kg/d for 7 days) and IVIg (0.5 g/kg/d for 5 days) found no difference in outcomes among the 3 treatments.13 One advantage, though, of IVIg is that it can be administered as a single IV dose, rather than multiple doses over several weeks, as is the case with oral prednisone.9,11-13

Follow platelet counts closely. Patients with ITP should have their platelet counts monitored at least once weekly and as often as twice weekly. The frequency of monitoring may be tapered depending on an individual patient’s response to treatment and the severity of the thrombocytopenia.14

We referred our patient to a nearby children’s hospital, where a repeat CBC showed her platelets had decreased to 3000/mcL. She received a 6-hour infusion of IVIg and was discharged with instructions to have her CBC closely monitored. Her platelets remained stable until 4 weeks later, when they decreased from 102,000/mcL to 71,000/mcL. She received a second infusion of IVIg as an outpatient.

Soon after, she went to our ED with a headache, nausea, and fever of 102°F. A computed tomography scan of her head was normal; a repeat CBC showed no elevation in white blood cells but her hemoglobin had decreased from 11.9 g/dL to 9.7 g/dL. (Her platelets were 254,000/mcL.) The patient’s complaints were likely adverse effects of the IVIg. The CBC abnormalities, fever, headache, and malaise resolved shortly thereafter and the patient remains asymptomatic with no recurrence of ITP.