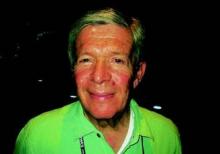

MAUI, HAWAII – Don’t look for findings about the human microbiome to have any imminent impact on health, said rheumatologist Peter Lipsky.

The human microbiome “is the most exciting area in science at the moment, but also the most hyped. There’s a tendency in this field driven both by scientists and the NIH [National Institutes of Health], as well as by commercial interests, to explain every [condition as it relates to] the microbiome,” he said at the 2015 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Most of our understanding about the microbiome comes from “very reductionist experiments” in genetically altered mice, often raised in germ-free environments “where you can control everything.” The findings have no clear use in human medicine, and have not led to any breakthroughs. To date, there have been only a few microbiome studies in people, and they’ve been solely descriptive, said Dr. Lipsky, former chief of the autoimmunity branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Microbiome research examines how normal human bacteria might have something to do with illness. The field has much in common with human genome mapping in the mid-1990s; it is in the data-gathering phase with little evidence of benefit.

It will take decades to fully figure out how vast and ever-changing communities of bacteria interact with each other and the human body, and how to selectively manipulate them to improve human health. Humans carry about 3 pounds of bacteria on and in their bodies, with bacterial cells outnumbering human cells by about 10:1. Those 3 pounds are composed of thousands of bacterial species, and new species are being discovered almost daily, thanks to advances in molecular technology.

“It’s impossible with the technology that we have now to integrate the actions of all these organisms,” said Dr. Lipsky of Charlottesville, Va.

Even so, the Internet is awash in ads for prebiotics, probiotics, and other products to balance the human microbiome. There are companies that take stool samples to diagnose and correct microbiome imbalances.

“Does this make any sense today? No,” Dr. Lipsky said. “You are never going to be able to stop patients from taking risks, but there is a certain amount of caution that needs to be exerted here. What you can tell patients is that this is an exciting area, but it’s in its early stage. There is really no scientific basis for any of these products. Most of them probably don’t do any harm, but I don’t know that for certain. The same organism that might protect against colon cancer could facilitate rheumatoid arthritis or periodontal disease,” he said.

Dr. Lipsky supported his thesis with a review of the latest human findings. One study found an aberration in oral microbiota in new-onset rheumatoid arthritis (RA). A stool sample study correlated an overabundance of gut Prevotella copri with RA. Another found changes in gut bacteria in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis that seem similar to those seen in inflammatory bowel disease. It’s unknown if the disease caused the imbalance or visa versa.

Another small study found a drop in gut Firmicutes families in lupus (mBio 2014;5:e01548-14). “How and why this microbial community influences [lupus] remains to be elucidated,” the authors noted.

Dr. Lipsky is an adviser for Janssen and a consultant for Pfizer.