Hepatitis A virus (HAV) can result in acute infection characterized by fatigue, nausea, jaundice (yellowing of the skin) and, rarely, acute liver failure and death.1,2 In the US, HAV yearly incidence (per 100,000) has decreased from 11.7 cases in 1996 to 0.4 cases in 2015, largely due to the 2006 recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that all infants receive HAV vaccination.3,4

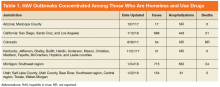

In 2017, multiple HAV outbreaks occurred in Arizona, California, Colorado, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah with infections concentrated among those who were homeless, used illicit drugs (both injection and noninjection), or had close contact with these groups (Table 1).5-7

These HAV outbreaks resulted in more than 1,000 hospitalizations and 45 reported deaths. The true scope of the outbreaks is believed to be much larger, given that HAV cases are under-reported.8In response, the CDC has recommended the administration of HAV vaccine or immune globulin (IG) as postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) to people in high-risk groups including unvaccinated individuals exposed to HAV within the prior 2 weeks.5 While the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the Department of Veteran’s Affairs (VA) has not noted a significant increase in the number of reported HAV infections, there have been cases of hospitalization within the VA health care system due to HAV in at least 2 of the outbreak areas. The VA facilities in outbreak areas are responding by supporting county disease-control measures that include ensuring handwashing stations and vaccinations for high-risk, in-care populations and employees in direct contact with patients at high risk for HAV.

This review provides information on HAV transmission and clinical manifestations, guidelines on the prevention of HAV infection, and baseline data on current HAV susceptibility and immunization rates in the VHA.

Transmission and Clinical Manifestations

Hepatitis A virus is primarily transmitted by ingestion of small amounts of infected stool (ie, fecal-oral route) via direct person-to-person contact or through exposure to contaminated food or water.9,10 Groups at high risk of HAV infection include those in direct contact with HAV-infected individuals, users of injection or non-injection drugs, men who have sex with men (MSM), travelers to high-risk countries, individuals with clotting disorders, and those who work with nonhuman primates.11 Individuals who are homeless are susceptible to HAV due to poor sanitary conditions, and MSM are at increased risk of HAV acquisition via exposure to infected stool during sexual activity.

Complications of acute HAV infection, including fulminant liver failure and death, are more common among patients infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV).12,13 While infection with HIV does not independently increase the risk of HAV acquisition, about 75% of new HIV infections in the US are among MSM or IV drug users who are at increased risk of HAV infection.14 In addition, duration of HAV viremia and resulting HAV transmissibility may be increased in HIV-infected individuals.15-17

After infection, HAV remains asymptomatic (the incubation period) for an average of 28 days with a range of 15 to 50 days.18,19 Most children younger than 6 years remain asymptomatic while older children and adults typically experience symptoms including fever, fatigue, poor appetite, abdominal pain, dark urine, clay-colored stools, and jaundice.2,20,21 Symptoms typically last less than 2 months but can persist or relapse for up to 6 months in 10% to 15% of symptomatic individuals.22,23 Those with HAV infection are capable of viral transmission from the beginning of the incubation period until about a week after jaundice appears.24 Unlike HBV and HCV, HAV does not cause chronic infection.

Fulminant liver failure, characterized by encephalopathy, jaundice, and elevated international normalized ratio (INR), occurs in < 1% of HAV infections and is more common in those with underlying liver disease and older individuals.13,25-27 In one retrospective review of fulminant liver failure from HAV infection, about half of the patients required liver transplantation or died within 3 weeks of presentation.12

Other than supportive care, there are no specific treatments for acute HAV infection. However, the CDC recommends that healthy individuals aged between 1 and 40 years with known or suspected exposure to HAV within the prior 2 weeks receive 1 dose of a single-antigen HAV vaccination. The CDC also recommends that recently exposed individuals aged < 1 year or > 40 years, or patients who are immunocompromised, have chronic liver disease (CLD), or are allergic to HAV vaccine or a vaccine component should receive a single IG injection. In addition, the CDC recommends that health care providers report all cases of acute HAV to state and local health departments.28

In patients with typical symptoms of acute viral hepatitis (eg, headache, fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea) and either jaundice or elevated serum aminotransferase levels, confirmation of HAV infection is required with either a positive serologic test for immunoglobulin M (IgM) anti-HAV antibody or an epidemiologic link (eg, recent household or close contact) to a person with laboratory-confirmed HAV.5 Serum IgM anti-HAV antibodies are first detectable when symptoms begin and remain detectable for about 3 to 6 months.29,30 Serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-HAV antibodies, which provide lifelong protection against reinfection, appear as symptoms improve and persist indefinitely.31,32 Therefore, the presence of anti-HAV IgG and the absence of anti-HAV IgM is indicative of immunity to HAV via past infection or vaccination.