The diagnostic process, as currently understood

Much of what is understood about the cognitive processes involved in diagnostic reasoning is built on research done in the field of behavioral science—specifically, the foundational work by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the 1970s.4 Only relatively recently has the medical field begun to apply the findings of this research in its attempt to understand how clinicians diagnose.1 This work led to the description of 2 main cognitive pathways described by Croskerry and others.5

Type 1 processing, also referred to as the “intuitive” approach, uses a rapid, largely subconscious pattern-recognition method. Much in the same way one recognizes a familiar face, the clinician using a type 1 process rapidly comes to a conclusion by seeing a recognizable pattern among the patient’s signs and symptoms. For example, crushing chest pain radiating to the left arm instantly brings to mind a myocardial infarction without the clinician methodically formulating a differential diagnosis.4,5

Type 2 processing is an “analytic” approach in which the provider considers the salient characteristics of the case, generates a list of hypotheses, and proceeds to systematically test them and come to a more definitive conclusion.5 For example, an intern encountering a patient with a painfully swollen knee will consider the possibilities of septic arthritis, Lyme disease, and gout, and then carefully determine the likelihood of each disease based on the evidence available at the time.

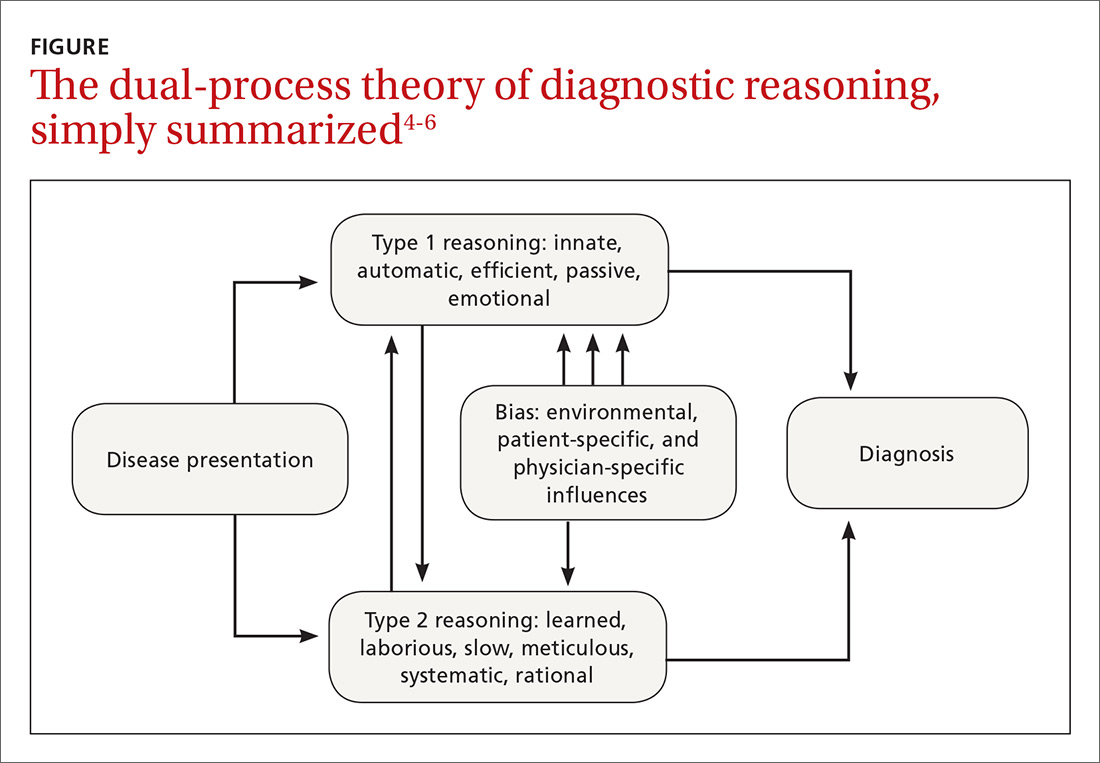

How the processes work in practice. While these 2 pathways are well studied within behavioral circles and are even supported by neurobiologic evidence, most clinical encounters incorporate both methodologies in a parallel system known as the “dual-process” theory (FIGURE).4-6

For example, during an initial visit for back pain, a patient may begin by relaying that the discomfort began after lifting a heavy object. Immediately the clinician, using a type 1 process, will suspect a simple lumbar strain. However, upon further questioning, the patient reveals that the pain occurs at rest and wakes him from sleep; these characteristics are atypical for a simple strain. At this point, the clinician may switch to a type 2 analytic approach and generate a broad differential that includes infection and malignancy.

Continue to: Heuristics: Indispensable, yet susceptible to bias