Premature closure is another well-known bias associated with diagnostic errors.2,6 This is the tendency to cease inquiry once a possible solution for a problem is found. As the name implies, premature closure leads to an incomplete investigation of the problem and perhaps to incorrect conclusions.

If police arrested a potential suspect in a crime and halted the investigation, it’s possible the true culprit might not be found. In medicine, a classic example would be a junior clinician presented with a case of rectal bleeding in a 75-year-old man who has experienced weight loss and a change in bowel movements. The clinician observes a small nonfriable external hemorrhoid, incorrectly attributes the patient’s symptoms to that finding, and does not pursue the more appropriate investigation for gastrointestinal malignancy.

Interconnected biases. Often diagnostic errors are the result of multiple interconnected biases. For example, a busy emergency department physician is told that an unconscious patient smells of alcohol, so he is “probably drunk and just needs to sleep it off” (anchoring bias). The physician then examines the patient, who is barely arousable and indeed has a heavy odor of alcohol. The physician, therefore, decides not to order a basic laboratory work-up (premature closure). Because of this, the physician misses the correct and life-threatening diagnosis of a mental status change due to alcoholic ketoacidosis.6

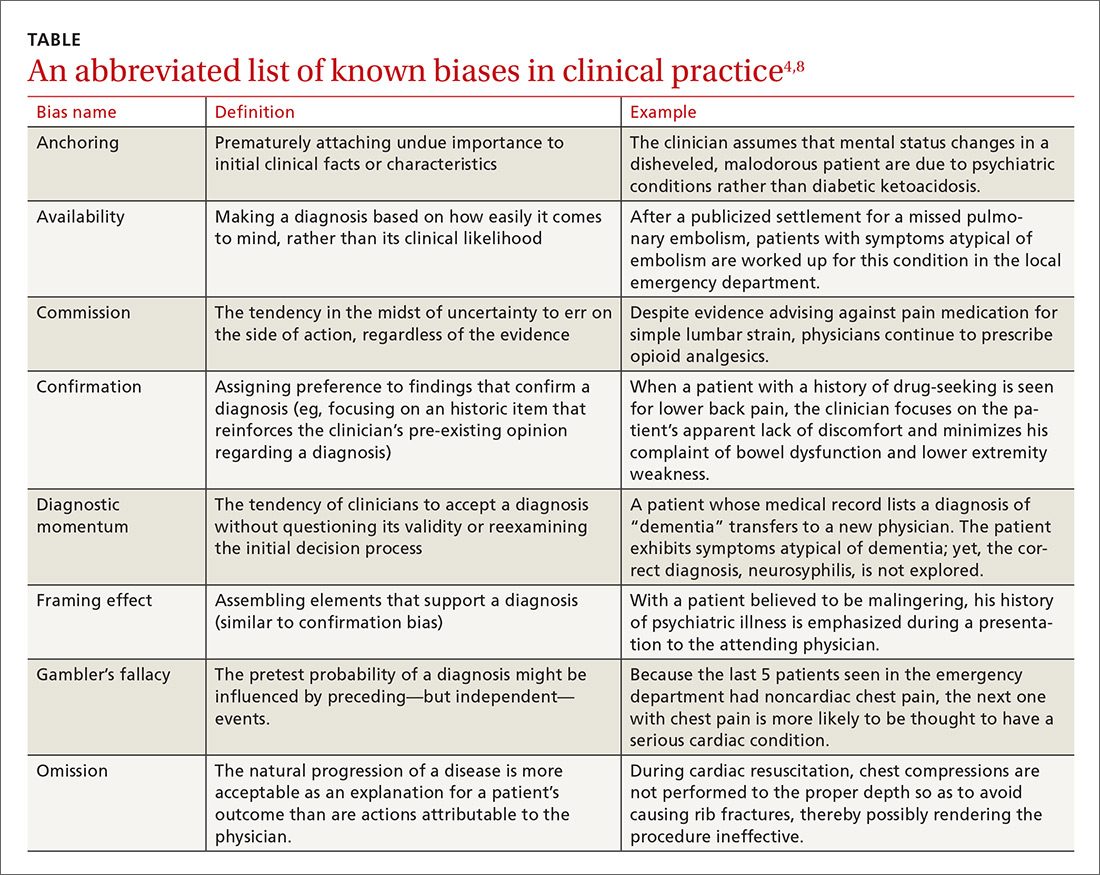

Numerous other biases have been identified and studied.4,8 While an in-depth examination of all biases is beyond the scope of this article, some of those most relevant to medical practice are listed and briefly defined in the TABLE.4,8

Multiple studies point to the central role biases play in diagnostic error. A systematic review by Saposnik et al found that physician cognitive biases were associated with diagnostic errors in 36.5% to 77% of case studies, and that 71% of the studies reviewed found an association between cognitive errors and therapeutic errors.6 In experimental studies, cognitive biases have also been shown to decrease accuracy in the interpretation of radiologic studies and electrocardiograms.9 In one case review, cognitive errors were identified in 74% of cases where an actual medical error had been committed.2

Continue to: The human component: When the patient is "difficult"