THE CASE

A 59-year-old woman from the Democratic Republic of the Congo presented to our family medicine clinic with acute worsening of longstanding headaches. Using a Swahili interpreter, the patient reported a 15-year history of recurrent, intermittent headaches that had been previously diagnosed as migraines. Over the prior 2 months, the headaches had intensified with new symptoms of dizziness, ocular pain, and blurred vision with red flashes. She had no hemiplegia, dysarthria, respiratory symptoms, night sweats, or weight loss. A neurologic exam was negative.

Before immigrating to the United States 14 years earlier, the patient lived for 6 months in a refugee camp in the Congo. At the time of her immigration, she was negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and a tuberculosis (TB) skin test was positive. A chest x-ray was normal and she had no respiratory symptoms. Shortly after her immigration, she completed 6 months of isoniazid treatment for latent TB.

THE DIAGNOSIS

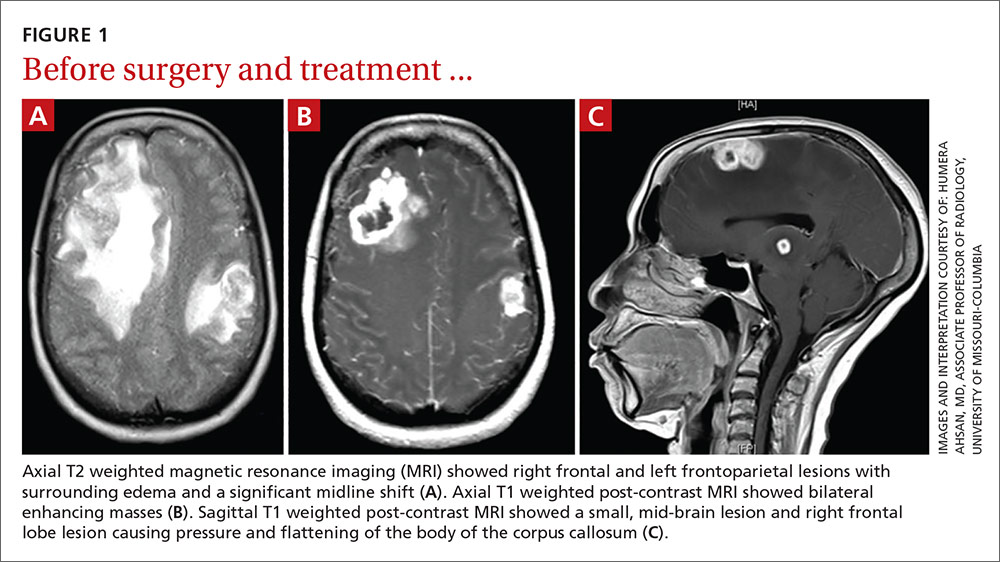

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s head demonstrated a large right frontal mass. The differential diagnosis included neoplasm, sarcoidosis, or, less likely, an infectious etiology. A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the brain showed multiple heterogeneous enhancing lesions, with the largest measuring 4.4 cm x 4.6 cm x 3 cm (FIGURE 1). Significant surrounding edema caused a 1.6-cm midline shift, subfalcine herniation, and impending uncal herniation. A CT of the abdomen and chest showed no pulmonary masses or metastatic disease, but did reveal a single 1-cm lymph node in the mediastinum and a 1.2-cm right axillary node.

A craniotomy was performed, which confirmed a large mass adhered to the dura. Surgeons removed the mass en bloc; pathology was consistent with a necrotizing granuloma. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining of 3 specimens was negative. Because the tissue was preserved in formalin, mycobacterial cultures could not be obtained. A cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed lymphocytosis and elevated protein, consistent with neurotuberculosis. Blood testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis with interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) was negative, as was testing for HIV 1 and 2. In addition, induced sputum was AFB-smear negative, as was an M tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction test.

Despite the negative AFB stain and negative IGRA, the patient’s findings were suspicious for TB, so we began to treat her empirically for neurotuberculosis with a 4-drug regimen (isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol).

In an attempt to confirm the diagnosis of TB and determine sensitivities, we performed a right axillary lymph node biopsy and sent it to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), along with the preserved neural tissue. Using a newly developed technique, the CDC amplified and sequenced mycobacterial DNA from both the central nervous system (CNS) mass and the axillary node, confirming M tuberculosis complex species. Cultures from the axillary node grew pan-sensitive M tuberculosis.

DISCUSSION

About one-third of the world’s population has either active or latent TB.1 In areas where TB is endemic, tuberculomas have accounted for up to 20% of intracranial masses.2 In non-endemic regions, however, they are relatively uncommon. The 3 manifestations of active CNS TB are meningitis, tuberculoma, and abscess.3 The clinical presentation and imaging studies of CNS TB are often indistinguishable from those of patients with malignant neoplasms or metastatic disease. Biopsies may be necessary to distinguish tuberculomas from other intracranial lesions such as pyogenic abscesses or necrotic tumors.4 Mycobacterial cultures were not done on the brain biopsies of our patient because of the high clinical suspicion for neoplasm. Axillary lymph node tissue ultimately confirmed the diagnosis and provided sensitivities.

A diagnosis of CNS tuberculoma without meningitis can be challenging because the clinical presentation is often vague, mild, or even asymptomatic. Constitutional symptoms may include headache, fever, and anorexia.5

In our patient, IGRA testing was also negative. For latent TB, IGRAs are considered to be at least as sensitive as, and considerably more specific than TB skin testing, but their use in CNS TB is less well understood. Studies evaluating IGRA sensitivity for TB meningitis show variable results. In one study, IGRAs were positive in only 50% of culture-confirmed cases of TB meningitis in an HIV-negative population.6