The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE 1 Fluid-filled abdominal mass

A 14-year-old girl complains of crampy, episodic, lower abdominal pain of 3 months’ duration and acute retention of urine. She also reports back pain and dyschezia. She has never menstruated, but her breasts began developing 18 months earlier. Examination reveals normal Tanner stage 3 breast development and female hair distribution and a large abdominal mass. No fetal heart tones are apparent. The external genitalia appear to be normal except for a bulging mass at the introitus.

Imaging (FIGURE 1) reveals that the mass is fluid-filled. The uterus, tubes, and ovaries are present at the dome of the mass. The kidneys are normal.

What is the mass?

FIGURE 1 No exit for menstrual products

An MRI shows a large hematocolpos that develops after menarche in women who have outflow obstruction, such as imperforate hymen—as this patient had.A list of the processes involved in normal development of the female reproductive tract highlights its precarious complexity: cellular differentiation, migration, canalization, fusion, and programmed cell death. A failure in any of these processes can cause a malformation. When that malformation becomes apparent depends on the stage of life of the patient and the nature of the abnormality. As you might imagine, diagnosis and treatment are not always straightforward.

In the patient just described, the likely diagnosis is imperforate hymen or transverse vaginal septum due to failed canalization of the vaginal plate. The patient has been menstruating internally for many months and now has a large hematocolpos. Urinary retention develops when the amount of retained blood in the vagina causes acute angulation of the urethrovesical junction. Evacuation of the blood restores the physiologic angle, enabling the patient to void normally.

Most anomalies involving the external genitalia are apparent at birth (clitoromegaly, imperforate hymen), whereas obstructive and nonobstructive malformations may become evident at birth; during childhood, puberty, or adolescence; or with menarche or childbearing.

Treatment of these abnormalities has changed significantly over the past few years—largely due to refinements in diagnostic imaging, surgical and nonsurgical techniques, and instrumentation. These advances have improved reproductive function and enhanced the psychosexual attitude of these patients.

In this article, I review the most common abnormalities and describe their evaluation and management.

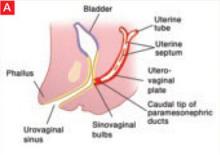

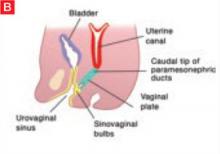

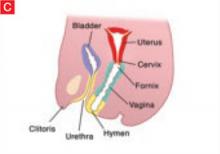

Vaginal canalization

The sinovaginal bulbs are two solid evaginations originating from the urogenital sinus at the distal aspect of the müllerian tubercle, as shown at right (A). The sinovaginal bulbs proliferate into the caudal end of the uterovaginal canal to become the solid vaginal plate (B). The lumen of the lower vagina is formed by degeneration of the central cells of this vaginal plate, which occurs in a cephalad direction (C). This process of canalization is complete by 20 weeks’ gestation.

Hymen usually ruptures before birth

The vaginal hymen is separated from the urogenital sinus by the hymeneal membrane. The hymen usually ruptures before birth with the degeneration of central epithelial cells (i.e., canalization), leaving a thin fold of mucous membrane around the vaginal introitus.

Uterus, fallopian tubes develop from solid tissue

The müllerian ducts are first identifiable at approximately 6 weeks of gestation, when they begin to elongate caudally and cross the metanephric ducts medially to meet in the midline. By the seventh week, the urorectal septum has developed, separating the rectum from the urogenital sinus. Around 12 weeks’ gestation, the caudal portion of the müllerian ducts fuses to form the uterovaginal canal, which inserts into the dorsal wall of the urogenital sinus at Müller’s tubercle.

The two müllerian ducts are initially solid tissue and lie side by side. Subsequently, internal canalization of each duct produces two channels divided by a septum that is reabsorbed in a cephalad direction by 20 weeks. The cranial unfused portions of the müllerian ducts develop into the fimbria and fallopian tubes, whereas the caudal, fused portions form the uterus and upper vagina.

Impaired canalization

Imperforate hymen

The most common obstructive lesion of the female reproductive tract is an imperforate hymen. It can be diagnosed at birth with careful examination to ensure patency of both the rectum and vagina. Not infrequently, the infant presents with a bulging introitus due to mucocolpos from vaginal secretions stimulated by maternal estrogen (FIGURE 2). If diagnosis is delayed, the mucus usually resorbs and the child remains asymptomatic until menarche, when she presents with a bulging hymen and a large hematocolpos, as in the opening case. Management of imperforate hymen is feasible for the generalist. Repair can be performed in a patient of any age, but is facilitated if the tissue has undergone estrogen stimulation. Surgery is, therefore, ideal in the neonatal, postpubertal, and premenarchal periods.