Migraine. Mood disorders are common among patients who suffer from migraine. The rate of depression is 2 to 4 times higher in those with migraine compared with healthy controls.16,17 In a large-scale study, patients with migraine had a 1.9-fold higher risk (compared with controls) of having a comorbid depressive episode; a 2-fold higher risk of manic episodes; and a 3-fold higher risk of both mania and depression.18 In a study of 62 inpatients, Fasmer19 reported that 46% of patients with unipolar depression and 44% of patients with bipolar disorder experienced migraine (77% of the bipolar disorder patients with migraine had bipolar II disorder). Patients with migraine are at increased risk of suicide attempts (odds ratio 4.3; 95% CI, 1.2-15.7).20

Tension-type headache. The relationship between psychiatric comorbidity in tension-type headache is well established. In contrast to what is seen with migraines, Puca et al21 found a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders (52.5%) than depressive disorders (36.4%) in patients with tension-type headache. Generalized anxiety disorder was one of the most prevalent anxiety conditions (83.3%), and dysthymia was the most prevalent mood disorder (45.6%). In the same study, 21.7% of patients were found to have a comorbid somatoform disorder.21

Emotional and cognitive factors can co-occur in patients with tension-type headache and a comorbid psychiatric condition. For example, difficulty identifying or recognizing emotions—commonly referred to as alexithymia—has been linked to tension-type headache.22 Additionally, maladaptive cognitive appraisal of stress is more common among patients with tension-type headache when compared with those without headaches.23 Being mindful of and recognizing these co-occurring emotional and cognitive factors will help clinicians construct a more accurate assessment and effective behavioral treatment plan.

Clinical assessment with a useful mnemonic

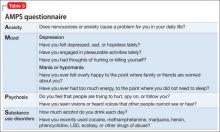

Clinical assessment of psychiatric illness is essential when evaluating chronic pain patients. Using the acronym AMPS (Anxiety, Mood, Psychosis, and Substance use disorders) (Table 3) is an efficient way for the clinician to ask pertinent questions regarding common psychiatric conditions that could have a direct effect on chronic pain.24 Head pain can be more intense when combined with untreated anxiety, depression, psychosis, or a substance use disorder. Untreated anxiety, for example, can amplify sympathetic response to pain and complicate treatment.

Investigating head pain patients for an underlying mood disorder is essential to providing successful treatment. Consider:

• starting psychotherapy modalities that address both pain and psychiatric illness, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

• reframing unhelpful pain beliefs

• managing activity-rest levels

• biofeedback

• supportive group therapy

• reducing family members’ reinforcement of the patient’s pain behavior or sick role.25

Assessing for somatic symptom disorders

In addition to using the AMPS approach for psychiatric assessment, clinicians should evaluate for somatization, which can present as head pain. Somatic symptom disorders (SSD) are a class of conditions that are impacted by affective, cognitive, and reinforcing factors that might or might not be consciously or intentionally produced. Patients with an SSD have somatic symptoms that are distressing or cause significant disruption of daily life because of excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors related to the somatic symptoms, for ≥6 months. The Figure outlines SSD, related conditions, and their respective prominent symptoms to assist in the differential diagnosis.26

Note that some headache conditions present with severe distress because of their abrupt onset and severity of symptoms (eg, cluster headaches). Therefore, the expectation and likelihood of psychological disturbance should be factored into a diagnosis of SSD and related conditions as seen in the Figure.

Secondary factors of unusual pain behavior or treatment response. The role of thoughts, affect, and behaviors is clinically meaningful in understanding SSD and similar conditions. Specific questions about cultural beliefs and rituals as they relate to exacerbations of head pain are of value. Table 413,27 lists behavioral, cognitive, and affective dimensions of head pain using the biopsychosocial model, and further clarifies common questions that arise with unusual pain response and complex patient presentations, which were outlined in the beginning of the article.

Because depression and anxiety can be comorbid with head pain, it is important to recognize psychological factors that contribute to pain perception. Indifference or denial of emotional stress as a result of severe pain and disability can imply a somatization process, which could suggest emotional disconnection or dissociation from somatic functioning.28 This finding can be a component of alexithymia, in which a person is disconnected from emotions and how emotions impact the body. Therefore, recognizing alexithymia assists in identifying psychological factors when patients deny mood symptoms, particularly in tension-type headache.

Functional assessment to rule out the disproportional impact of pain on daily activities is helpful in understanding the somatization process. Neurocognitive functioning should be assessed, particularly because frontal and subcortical dysregulation has been observed in head pain sufferers.29,30 Patients with cognitive changes as a result of a medical illness (eg, stroke, head concussion, brain tumor, or seizures) are especially at risk for neurocognitive dysfunction.